One of the great things about Linux, and free software in general, is that it doesn't suffer the hyperbole that you find in other parts of the computer industry.

At least not in the user-community-developer sphere that we live in.

Our inbox rarely filters notifications of an imminent security disaster, for example, or messages marked as important because there's a new virus that's going to spread from our phones to our netbooks through our fridges.

If one of these emails does make it through, we enjoy replying by asking what impact this might have on Linux users. The response is nearly always: "What's Linux?"

The software, distributions and hardware emerging from the world of open community development often prefer to float on their own merits rather than those of a PR company. One exception might be the discussion on whether 2012 will be the year of Linux on the desktop, but that was a joke, and one long past its best.

But there's another exception, and that's the perennial Ubuntu.

Ubuntu is breaking away from the tradition of a free software company by ramping up both expectation and anticipation for its own products in ways usually associated with its proprietary competitors.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

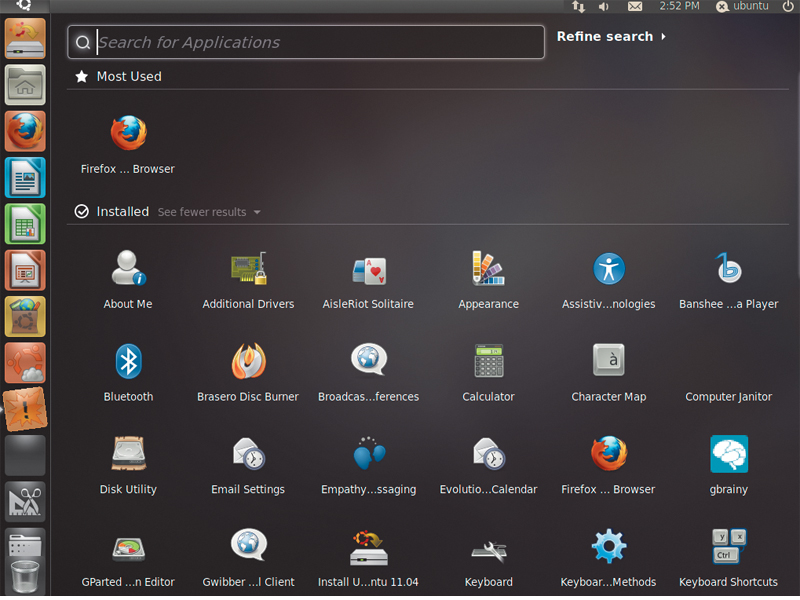

In some aspects, this is brilliant. The slick and professional HTML5 demo site that accompanied the release of 11.10, for instance, was a wonderful taster of what the Ubuntu desktop feels like. It fulfilled a genuine purpose by helping the uninitiated realise that Linux isn't just the command line or a wasted weekend trying to get audio to work.

It can actually be a slick desktop that looks as good as the latest release of OS X, and far better than that version of Windows where you can't even change the desktop background image. No other Linux distribution puts that amount of effort into trying to win new users, and Ubuntu deserves plenty of new ones as a result of that initiative.

Talkin' loud

Ubuntu has every right to shout about its success. It's still the most popular Linux distribution, and takes great pains to create a user experience that's different from other distributions.

But the team behind Ubuntu is also getting more proactive and shouty about its own largess and self-perpetuating prophesies - and it starts at the top. Mark Shuttleworth, Ubuntu's benevolent dictator for life, wrote on his blog that he wants to see "Ubuntu on phones, tablets, TVs and smart screens everywhere" by the time 14.04 is released (in just over two years).

This statement comes only months after he told the Ubuntu Developer's Conference in Budapest that he wanted to see 200 million users within four years. A good plan, and some nice big numbers, but we have difficulty believing Ubuntu will come close.

Without any question, if either of those goals were realised, we'd be ecstatic. We want Ubuntu to win. But we don't want its advantages and achievements to be lost in a cloud of moon-gazing rhetoric.

Numbers game

If, in 2015, Ubuntu has 200 million users, let's all have a party and we'll say sorry. Ubuntu would be an unprecedented success. But when the Ubuntu team can't even give you an accurate measure of how many people are using the distribution today, or how they're estimating their numbers, how can we trust predictions for the future?

Mark also mentioned, for example, that there are currently around 20 million Ubuntu users, up from their estimate of 12 million in 2010. That's a very healthy result, but why the secrecy in how these numbers are formed?

Why not open up how these figures were calculated and let us see the 10 times growth predicted for Ubuntu over the next few years ourselves. That way we can all celebrate.

This is something the Fedora project does, for example. The Fedora wiki statistics page lists as much data as it can, including unique IP access to the downloads in a week-by-week table, complete with percentage comparisons against the previous release and updates through the package repository.

This page also includes the important disclaimer about how the exact number of users can't be derived from these statistics alone.

But you can't argue against the openness in the statistics or the growth in Fedora's popularity from one release to the next. The numbers are in front of you, and we think the Ubuntu team should be prepared to do the same, especially when they're making such bold predictions for the future of their distribution.

Openness and transparency is what makes open source software development as brilliant as it is, and it's something our competitors can't touch. They should be our weapons of choice when it comes to marketing, not hyperbole.