The philosophy of free software

The place for open source in the wider ethical, economic and religious world

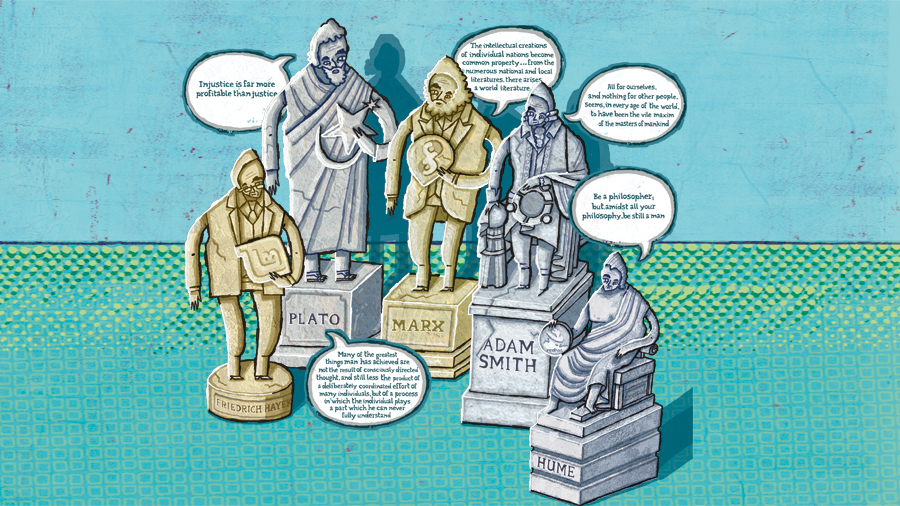

People love a good debate. We asked (with tongues in our cheeks) whether Linux was best understood as being Marxist or capitalist.

The comments that followed were a lot of fun, but most were also well thought out and got us thinking about how Linux and the free software movement fit in to some of the wider philosophical, economic, religious and ethical debates that have pre-occupied human beings over the centuries.

Seeing as even Linus Torvalds has been engaging in such idle speculation, as was shown in his summertime interview with the BBC, we thought it would be fun to continue the conversation.

We're going to take a sideways look at Linux and free software by exploring it through the guise of several of these ongoing debates, taking a look at a few theories and seeing how they might be applied to our favourite operating system.

A warning first: to us, the most important thing about Linux and free software is that it's a practical reality. It's simply cool that this stuff works, it's free and people can have great fun using and making it - and some can even make a bit of money at the same time. Everything else is just gravy, so don't get too upset by anything you read!

Having mentioned Linus Torvalds' interview with the BBC, let's start there. In it, he said "…open source only really works if everybody is doing it for their own selfish reasons… the fundamental property of the GPL v2 is a very simple 'tit-for-tat' model: I'll give you my improvements, if you promise to give your improvements back."

What makes Torvalds' observation interesting is that it links in with discussions in philosophy, ethics, biology, psychology and even mathematics dating all the way back to Plato (at least!). In The Republic, Plato is discussing justice and morality, and wondering whether these are a social construction or some abstract good.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

In doing so, Glaucon, one of the characters, proposes the idea of a magic ring that makes the wearer invisible. He suspects that both a just and an unjust person wearing the ring would act in the same way: taking what they like from the market, going into houses and "lying" with anyone they fancy, or killing their enemies.

He says: "If you could imagine any one obtaining this power of becoming invisible, and never doing any wrong or touching what was another's, he would be thought by the lookers-on to be a most wretched idiot…" since "... injustice is far more profitable than justice." What a depressing take on people!

Whether you agree with Glaucon or not, it's obvious this is the same point that Torvalds was making: without social constraints, such as the GPL v2, I wouldn't be able to trust that if I give you my code improvements, you'll give me yours back.

Why would you? After all, if you just took my code and continued to improve your software, you'd have an advantage over me, having to do less work for a better result - and people are selfish!

It seems that even Plato at least speculated, as did Torvalds, that the world doesn't work by everyone saying: "let's all sing Kumbaya around the campfire and make the world a better place."

Free riders and security

Bruce Schneier addresses the same problem in his latest book, Liars and Outliers, making it clear just how current this conversation is, both inside and outside the world of technology. In the book, he describes something called the hawk-dove game, from game theory.

The concept is that in a wild population of birds, all competing to share a limited amount of food, some birds are hawks and some doves. Hawks are aggressive and will fight for their food: when they meet another hawk, the two will fight, with one getting the food and the other being injured and possibly dying. Doves are passive, and when two meet over some food, opt to share it between one another instead. If a hawk and a dove meet, then the hawk will always get the food, as the dove will choose to retreat.