How Netflix works – 400 billion interactions per day ain't easy

37% of the internet and counting … and all from the cloud

Eight million events per second, and billions of metrics every minute. That's the staggering size of video streaming service Netflix, which now claims 37% of peak hours internet bandwidth in the US – and it's pushing towards being used by close to half the population.

The streaming video service, whose recent raising of its prices was headline news, is popular and expanding globally fast, but how does it work?

How big is Netflix?

"We're in 60 countries and expect to be in 200 by the end of 2016, so 65 million will turn to 100 million in a few years," says Josh Evans, Director of Operations Engineering at Netflix, speaking at AWS reInvent 2015 in Las Vegas in October. "We've just launched in Japan and we're going to launch in four other Asian countries in 2016."

Early 2016 will see Netflix launch in Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan, though some say Netflix is cherry-picking 'low hanging fruit', only operating in highly developed countries where a monthly subscription is affordable.

According to the most recent Sandvine Global Internet Phenomena Report, Netflix is making gains in new European markets they entered late last year, with the service now accounting for almost 10% of peak downstream traffic in both Austria and France.

"At peak we consume 37% of internet bandwidth in the US," says Dave Hahn, Senior Engineer, Critical Operations and Response Engineering Team (CORE) at Netflix in Los Gatos, California, who spoke to us after his talk 'A Day in the Life of a Netflix Engineer'.

The need for speed

There are thousands of people clicking play at the same time, with activity peaking in the evening, though as a global platform it's a constant peak.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

The challenge is how to run a service with zero loss while processing over 400 billion events daily, and 17GB per second during peak.

"Starts per second is the heartbeat of Netflix," says Evans. Pressing play is big business.

How the user interface works

You might have noticed that the way you interact with the Netflix user interface has recently changed.

"We created what we call our 'Darwin' user interface, moving form vertical to horizontal box shots, and we tuned our algorithms … a lot of innovation went in," says Evans.

The same kind of interface is on the website, too, creating what Evans calls the 'Akira' user interface.

"All the information you need is at your fingertips," he says. It sounds simple, but it's built on advanced telemetry, real-time analytics and advanced machine learning.

Is Netflix in the cloud?

Yes, but here comes the weird bit – Netflix is hosted by Amazon Web Services (AWS), whose Amazon Prime Instant Video it competes with.

"Everything that is Netflix from an operational standpoint lives on AWS with the exception of the video bits," says Hahn. It might seem odd, but Amazon actually helps Netflix address the unpredictable peaks in traffic.

"We rely on Amazon's elastic infrastructure to help us scale when we need to," says Hahn. "We go to them for the heavy lifting – for us to build a datacenter and run it really well doesn't help our customers enjoy entertainment, so we're more than happy to have a partner in Amazon that does that stuff for us."

However, it's perhaps a mistake to see AWS and Amazon as partners; the former only regards the latter as one of its customers.

Where does the video come from?

All video is cached and stored on Netflix's own OpenConnect content delivery network (CDN), which connects directly to Internet Service Providers (ISPs). This is the core of Netflix; it's where everything is stored, and it comes complete with cloud management, a delivery engine, and an automation platform.

"Everything else runs on top of AWS," says Hahn. "We built this CDN over the last few years with hardware that works with ISPs around the world."

The CDN is global, so wherever you are in the world, when you request a video the system selects the nearest location to stream it from.

It's in stark contrast to Netflix's past; which started as a DVD rental service, and then racked and stacked its own servers when it began streaming.

Has Netflix always been on Amazon?

No – it used to sit on Netflix's own data centres, specifically one single location on the West Coast of the USA.

This was five years ago, when Netflix wasn't the phenomenon in developed countries that it currently is.

Given its aggressive expansion plans, an easily expandable infrastructure like AWS was the answer. "We started building in 2009 and we had the first devices connect to AWS in 2010," says Hahn.

How does Netflix cope with regional content licensing?

It's complicated.

Hollywood and the movie and TV industry generally is one of the last vestiges of digital geography, which is why some shows are on Netflix US, Netflix Sweden or Netflix Canada, but not on Netflix UK, or vice versa.

It's often a case of there being multiple rights owners, where the studio who produced the movie having rights to sell in one country while a distributor has exclusive rights in another.

However, Netflix is trying to get around this archaic model by producing its own shows like Orange is the New Black, Marco Polo and the not-as-good-as-it-was House of Cards.

Some Netflix users try to get round geolocation restrictions by using a VPN to mask their location and thus browse Netflix libraries not technically available to them, but Netflix has to oppose this, at least officially.

Is it Netflix Vs Amazon Prime Instant Video?

It might appear that way, but since both services are built and run from AWS, Amazon is all too keen to support its main global video streaming rival.

Perhaps that's no surprise given its size, though there is evidence that streaming on Amazon Prime Instant Video is more popular.

Hulu Plus (USA only), the BBC iPlayer (UK only) and other territory-specific rivals aside, there's also iFlix, a startup in South East Asia that's aiming to gain traction in markets that Netflix has thus far ignored.

So far launched into Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand, iFlix charges a few dollars per month for everything from South Korean soap operas to Hollywood blockbusters (and several Hollywood power brokers sit on its advisory board).

Netflix won't completely dominate the globe, but video streaming likely will.

How much does Netflix know about what is being watched?

It knows everything.

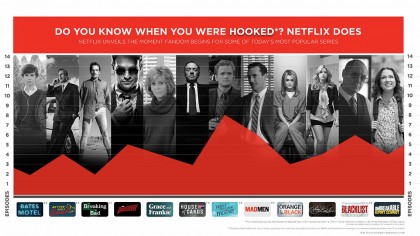

Every time you watch, browse or view a trailer, Netflix knows. By analysing its global streaming data it can tell the exact point that a show takes-off.

Think it's all about a great pilot show?

"No one was ever hooked on the pilot," says Ted Sarandos, Chief Content Officer for Netflix, who studied data from 20 shows across 16 markets. "This gives us confidence that giving our members all episodes at once is more aligned with how fans are made."

In short, binge-watching is what it's all about, or so says the data.

Netflix engineers managed to identify 'hooked' episodes where 70% of viewers who watched that episode went on to complete season one.

What's coming next for Netflix

While 65 million people might sound a lot, it's a drop in ocean compared to the amount of people Netflix could be streaming to, so growth (most immediately in Asia) is in Netflix's future.

Netflix streaming is also being made available to airline passengers with phones, tablets or laptops on 10 of Virgin America's new Airbus A320 aircraft in the US, though it's only free until beta testing on its new ViaSat inflight WiFi system ends in March 2016 (expect high prices thereafter for such a data-intensive app).

More important for Netflix as a whole is a more lively UI.

"You'll see more video incorporated into the user interface embedded directly into the UI, and all of this requires growth in the backend infrastructure," says Evans, who shows us a graphic of what the Netflix architecture looks like.

"That's simplified," he says of the complex, spiderweb-like image. "It's more like an organism than a computer programme."

We've also got HDR on the way next year, as Netflix works with the UHD Alliance to help finalise the broadcast standards. As well as an intermediary resolution between HD and Ultra HD for those without the bandwidth to go for the full UHD/HDR monty.

It's also working on new high-efficiency mobile encoders, because it doesn't believe its customers really want to go for the download route if they can stream without completely destroying their mobile data allowances.

And it's going to need a whole lot more Amazon space as it swallows up more and more of the internet.

Jamie is a freelance tech, travel and space journalist based in the UK. He’s been writing regularly for Techradar since it was launched in 2008 and also writes regularly for Forbes, The Telegraph, the South China Morning Post, Sky & Telescope and the Sky At Night magazine as well as other Future titles T3, Digital Camera World, All About Space and Space.com. He also edits two of his own websites, TravGear.com and WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com that reflect his obsession with travel gear and solar eclipse travel. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners (Springer, 2015),