The quest for open science

We talk to Dr Richard Bowman about designing 3D-printable microscopes

WaterScope

WaterScope, the company that Bowman co-founded, came out of a student project in the i-Teams Cambridge scheme (that includes the Raspberry Pi as past successful projects). Part of this scheme focuses on innovations that can be used in the developing world to improve people’s lives in a sustainable way.

Globally, 663 million people don’t have access to safe drinking water, so WaterScope decided to target testing for bacteria in water as it’s such a lengthy and fiddly process: “Testing for bacteria is difficult and inconvenient, so this means people don’t do it as much as they should,” says Dr Bowman. “You collect your water; you extract the bacteria from the water with a filter, you pass it through a filter with very small pores, less than micron. Next, you put your filter on some medium, so food, and you let them grow overnight and 18 hours later you look for the biggest, nasty bacteria splotches.

“The colonies will be big enough to see by eye [...]. If you’re working in a developing country where the infrastructure isn’t good, you probably don’t have access to a clean lab and if you do it’s probably some distance from where you are water testing. So you end up gathering your samples, going back to base and then you’ve got to sterilise everything, keep your work area clean and so on.”

The idea behind WaterScope is to make the test faster by doing it on a smaller scale. After all, says Bowman, “if you look at it with a microscope, you can see single bacteria directly,” and the equipment is small and portable and doesn’t require a lab and hopefully can be a little bit more digital. Bowman says if you can grow the bacteria, it should be possible to tell what sort of bacteria you’ve got, and that last part is something WaterScope is actively working on now.

The idea is to acquire a time-lapse video of an hour’s growth and then process it so you can automatically count the number of bacteria colonies. “You can save enough of that image data to verify later that everything has worked properly,” says Bowman.

WaterScope’s eventual goal is for technicians to be able to upload and map out the tests and turn it into a useful resource for people planning water provision. “We’ve now done our first proper field trials this summer out in Tanzania,” reveals Bowman. “We have seen bacteria growing. We’re confident we’ve got something that works, but we’re still working on how to identify what bacteria you’ve got in the field. The trouble is that a lot of the existing systems assume you’re doing a really long incubation and they only work after 4, 8 or 10 hours – we really want something that’s much faster, but it’s exciting progress.”

Acceleration through automation

Another exciting thing Bowman is working on involves the higher-specified version of his microscope. He points out some blood smears: “Those blue things inside the red blood cells,” he tells us. “Those are malaria parasites. And this is how a lot of malaria is diagnosed,” he says. “They will take a drop of blood and dry it out with some stain and someone will spend half an hour looking through your blood cells for those tell-tale rings.”

Are you a pro? Subscribe to our newsletter

Sign up to the TechRadar Pro newsletter to get all the top news, opinion, features and guidance your business needs to succeed!

Bowman is pushing hard to automate this process: “All my project proposals are working with computer vision folk to make this process more automatic [...]. The big benefit [to doing this] is that there aren’t enough technicians [...]. If this means that one technician can have ten microscopes running simultaneously because they are all automated then great. [...] If they refer a patient on to a hospital then they can send the slide digitally or even on paper, so they don’t have to redo the microscopy.”

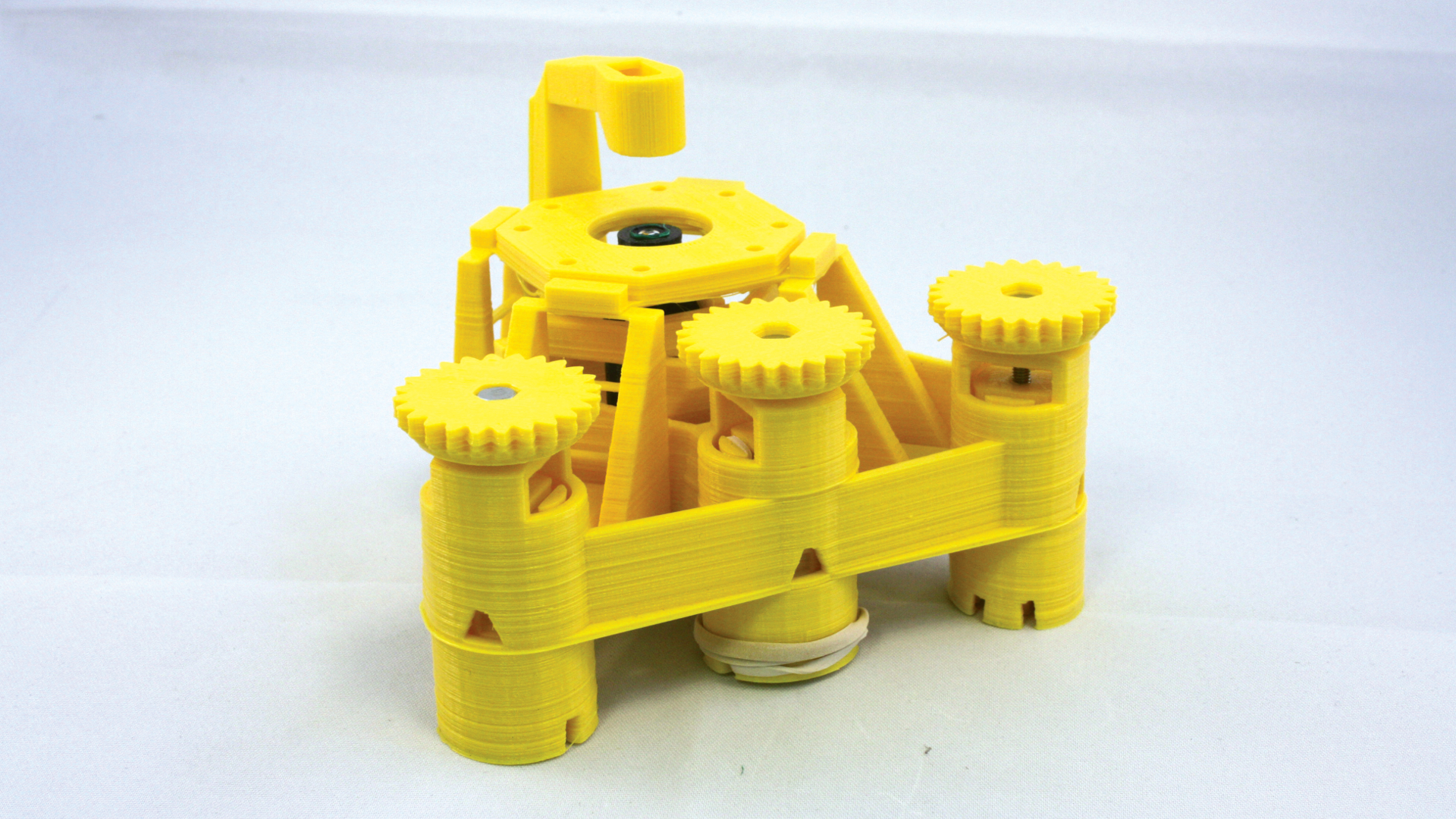

But the microscope is one part of the open science hardware dream: “One of the reasons I put so much effort into making the microscope print more or less in one piece on a bottom-of-the-range RepRap 3D printer is to get as close to that dream of being able to download and have a piece of hardware.” And Bowman admits it’s pretty close. “It takes maybe half an hour to put one of these together.”

Currently, Dr Bowman is collaborating on the computer vision with another academic at Bath University, Dr Neill D.F. Campbell, and they are currently applying for funding.

(This feature was first published in issue 185 of Linux User & Developer).

- Subscribe to Linux User and Developer today! Get an extra 20% off our Xmas subs deals using code: 20NOV. That’s up to 43% off PLUS an extra 20% off!

Chris Thornett is the Technology Content Manager at onebite, editor, writer and freelance tech journalist covering Linux and open source. Former editor of Linux User and Developer magazine.