The Tetris Effect: how four simple tiles can help anxiety and reshape your brain

From flow states to amnesia, the psychology behind the latest Tetris game

If you closed your eyes right now – and don’t actually do it, because then you won’t be able to read this article, but if you did – it’s a fairly safe bet that you could summon each of the seven tetrominoes into your mind’s eye. You know, those blocks, all made up of four tiles, that you’re constantly rearranging in a game of Tetris. Maybe you can even see their colours – depending on which version you’ve played most, it might be an orange ‘L’ shape, a skewed ‘S’ in green.

But what if you hadn’t decided to try and picture them? What if, when you closed your eyes at night, you saw those shapes tumbling across your vision? What if you started to see them overlaid onto pavestones or buildings or, rendered in a wholemeal-and-white monochrome, the loaves stacked on a supermarket shelf?

This is the Tetris Effect, a psychological phenomenon first given name by Wired writer Jeffrey Goldsmith in 1994. A name that, here in late 2018, has been adopted by an official Tetris game hoping to encourage and enhance these symptoms in its players.

“At its simplest, what we hope is that when you’re playing it, you’re not thinking about anything – you forget about your troubles and your cares and whatever,” says Mark MacDonald, VP production and biz dev at Enhance Games, the developer behind Tetris Effect. “When you’re not playing it, all you can think about is it.

“Why we chose the name, and what we’re trying to do with the game, has a lot to do with that first thing. We wanted to double down on that, put all of our chips into that feeling. While you’re in the game, you’re totally immersed in it, you’re out of your head, you’re not thinking about anything else. You might not even be thinking about the game – you’re just inside of it. You kind of lose yourself.”

Going with the flow

This is known as a ‘flow state’, and it’s the first of many fascinating things that playing Tetris does to our brains. As Mihály Csíkszentmihályi, the psychologist who first gave flow its name, explained it in a 2004 TED Talk:

“There's this focus that, once it becomes intense, leads to a sense of ecstasy, a sense of clarity: you know exactly what you want to do from one moment to the other; you get immediate feedback. You know that what you need to do is possible to do, even though difficult, and sense of time disappears, you forget yourself, you feel part of something larger.”

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Flow comes from nearly maxing out your brain, finding a perfect balance of challenge and skill level. As examples, Csíkszentmihályi points to everyone from poets to figure skaters, monks to CEOs. His prime example in the latter category is, coincidentally enough, Masaru Ibuka – who, by founding Sony in 1946, laid the foundations that would eventually result in Tetris Effect’s home platform, the PlayStation 4.

It can help ease anxiety, according to a University of California study published just a few weeks ago which used as its central testing mechanism – you guessed it – Tetris. Over 300 college students were told they were about to be evaluated on their attractiveness, just to stress them out, then given a version of the game to play while they waited. The students who were given a properly balanced version of Tetris – not too fast, not too slow, but perfectly Baby Bear – reported lower levels of negative emotions about their impending ‘hot or not’ judgment.

Tetris, in its almost primal simplicity, is a great way of achieving flow. As the rhythm of dropping tetrominoes speeds up, the idea that you’re controlling this by pushing buttons, or separated from the blocks by a flat screen, or even that you’re playing a game at all, can start to melt away.

“It’s a cool, magical feeling but normally you’d need to be really good at the game, or you’d have to play the game for a really long time to experience that,” says MacDonald. “We wanted to lower the barrier to entry so that anybody playing it, even if they’re not that good at Tetris, they could have that feeling.”

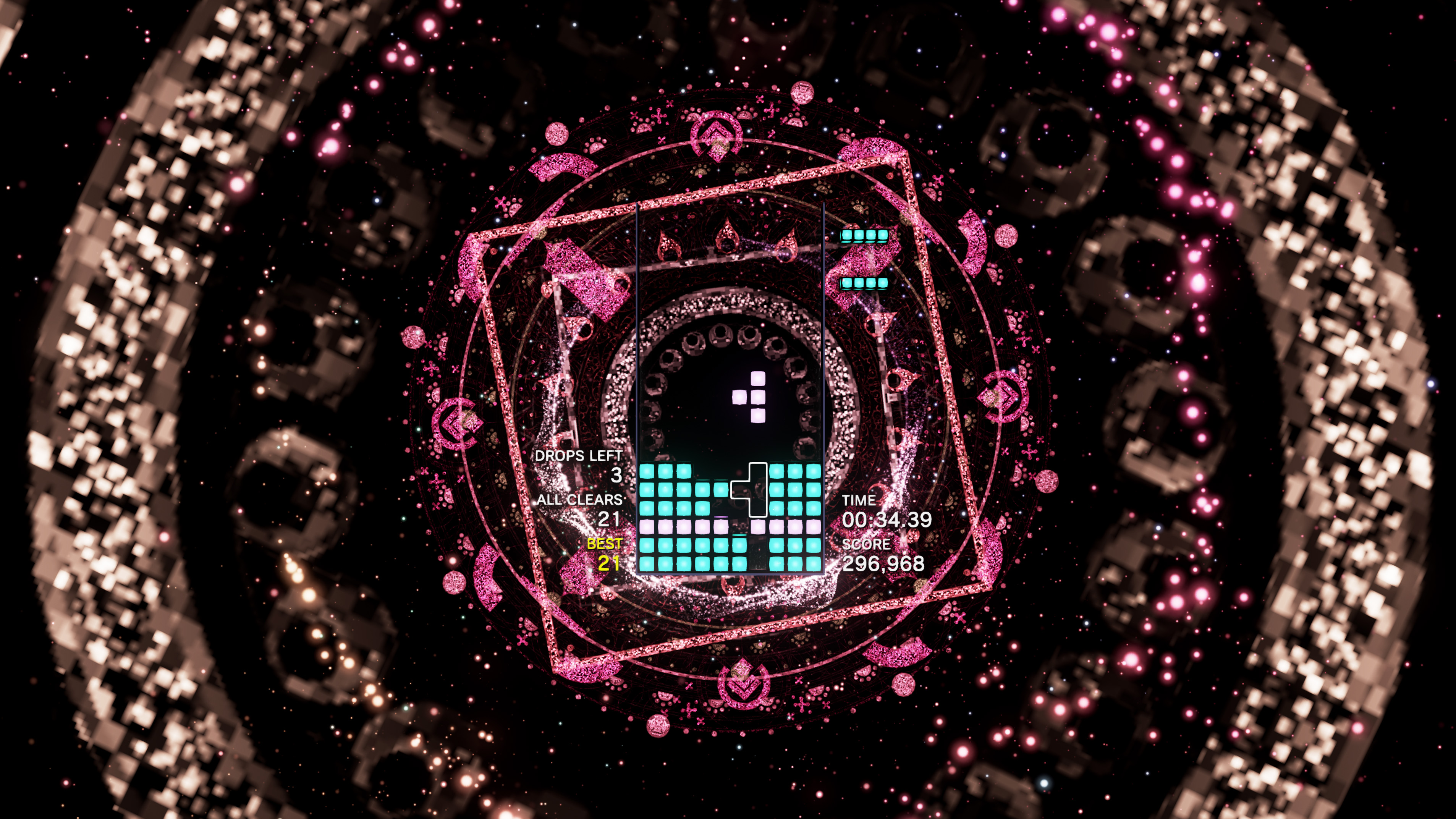

One of the ways that Tetris Effect does this is its Zone meter, which gradually fills up as you play. Squeeze a trigger and everything slows down, the music and particle effects fading away so you can concentrate on putting everything in its right place. It’s the concept of being ‘in the zone’, of hitting that flow state, neatly literalized into a mechanic within the game.

This is how the best players experience Tetris all the time, it seems. In 1992, neuroscientist Richard Haier led studies that showed how practiced players required less mental activity – a lower glucose metabolic rate, to be precise – to play the game at harder, faster levels. Tetris had made their brains more efficient.

It can even affect the shape of your grey matter. In 2009, Haier was part of another experiment, based on MRI scans of teenage girls’ brains. After a three-month period, the girls who had been playing Tetris on a regular basis showed significantly thicker cortexes than those who hadn’t spent the time lining up those seven blocks over and over again.

Stuck in your head

It’s when you step away from Tetris, however – just put down the controller and get on with your day-to-day life, or retire to bed – that things start to get really interesting.

Players often report seeing tetrominoes in their dreams, being able to play the game in their head during quiet moments, or sorting real-world objects into those four-tile patterns. If you haven’t experienced it for yourself, this might sound fantastical – but again, there’s plenty of scientific evidence to back it up.

A 2000 study at Harvard Medical School found that over 60% of players reported Tetris invading their dreams. When they expanded the study to include people suffering from anterograde amnesia, meaning they couldn’t form new memories – think Memento, the Christopher Nolan movie – something remarkable happened.

After seven hours of Tetris, spread across three days, the amnesiacs also reported seeing tetrominoes in their dreams – even though they had absolutely no memory of actually playing the game itself, or of the researcher who taught them how to play it.

“I see images that are turned on their side,” one of the amnesia sufferers told a researcher. “I don't know what they are from. I wish I could remember, but they are like blocks.”

This is the remarkable staying power of Tetris. It’s not the only game or activity that can do this, though. Similar effects have been reported with Rubik’s cubes and jigsaw puzzles. I personally have experienced it after lengthy sessions of Guitar Hero, those five coloured lines still racing towards me as I drifted off.

These all, notably, have something in common with Tetris. They’re relatively simple tasks of spatial reasoning, involving bright colours and clean shapes, and in the last example, a constant sense of rhythm.

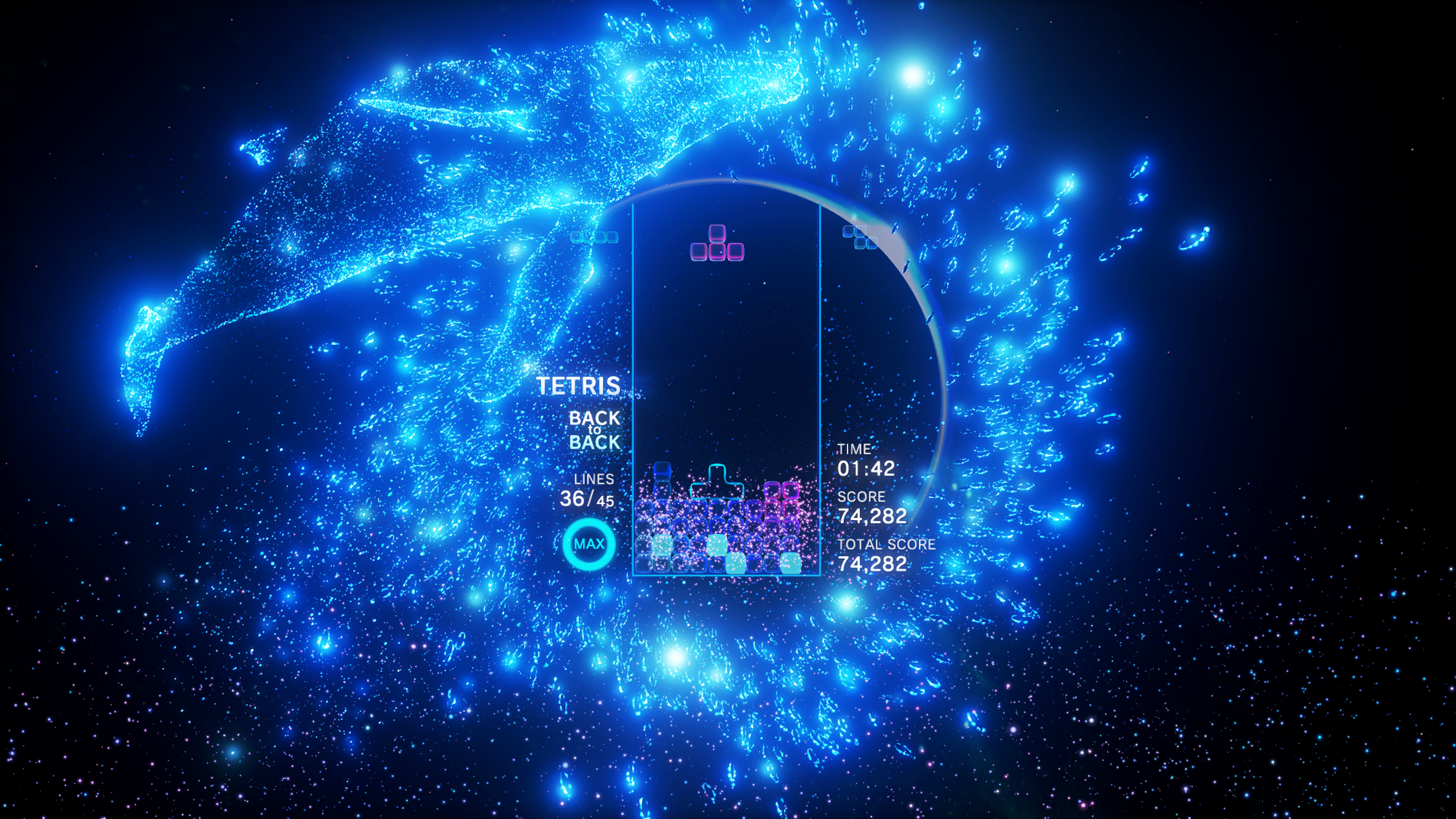

Once again, Tetris Effect is doubling down on this effect. As you rotate blocks and clear lines, the game surrounds you with glittering spectacle. You might find yourself on a beach at dusk, or soaring above a forest in the rain, or dashing through a minimalist cityscape. The last one in particular, with the hard right angles of its tower blocks and glittering grids of an overlaid subway map, is an effective illustration of the kind of Tetris-like patterns you might see in the real world.

As you play, each stage reacts in a unique way. Rotating a block will trigger a sound effect relevant to the world you currently find yourself in. Clearing a line will reward you visually – causing a fire to flare up and bathe the blocks in orange light, or dolphins to leap from the glittering ocean below you. Keep clearing, and the stage itself will start to change, revealing new aspects or transporting you to somewhere different.

And under it all lies that stage’s trademark song, which also develops as you play, making it all feel like you’re conducting the world’s greatest light show.

“With this game, hopefully what lingers is not just the stuff that lingers with a typical Tetris game,” says MacDonald. “What we want you to be thinking about is not just the gameplay, but a really striking image you saw – or the music, like an earworm song that you can’t get out of your head.”

So, even if the blocks don’t get you, the music might. I’ve spent the past fortnight obsessed with Tetris Effect’s opening track, “I’m Yours Forever”, and as I listen to hour-long edits of the song on YouTube, I can see the pulsing blue lights of the stage it soundtracks, imagining myself assembling shapes in time to its beat.

I’m reminded of something Alexey Pajitnov, the creator of the original Tetris, says in the Wired article that first coined the term ‘Tetris Effect’: “Playing games is a very specific rhythmic and visual pleasure. For me, Tetris is some song which you sing and sing inside yourself and can't stop."

For all the science underpinning Tetris Effect, this quote is the perfect summary of what the game achieves. It takes the most perfectly simple game and shows how it can be as catchy, magical and brain-chemistry-altering as a great pop song. Just don’t be surprised if you’re still humming its tune days later.

Alex Spencer is a purveyor of high-quality words. He is a freelancer at Polygon, Kotaku, Edge, RPS, etc.