The VFX wizards behind Planet of the Apes turned me into a chimp and it was bananas

Chimpin' ain't easy

Since starring as Gollum in The Lord of the Rings films, Andy Serkis has helped permanently change the way Hollywood approaches digital characters, and through his continuing work in the field of motion capture performance, the British actor has brought life to the kinds of characters that were once thought impossible to realize on-screen.

Gollum (and Smeagol) are undeniably iconic characters, but we'd argue that Serkis' work in the rebooted Planet of the Apes trilogy may very well end up being his crowning achievement. The actor's performances as leading-ape Caesar are so convincing that he completely disappears into his character, an intelligent ape-revolutionary who wants nothing more than for his kind to be left in peace.

While I'm all for giving the man behind the digital mask a much-deserved Oscar, the talented animators and visual effects artists at New Zealand-based Weta Digital deserve just as much credit for their part in taking Serkis' raw performance data and finessing it into the incredible achievement you see in the final product.

Given the number of dots placed on the actors' faces during the motion capture process, you'd be forgiven for thinking that the recorded facial data is simply transferred directly to a digital ape counterpart. In fact, countless man hours are spent matching that facial data, frame by frame, to the actor's digital 'puppet', the idea being that the end result should look as ape-like as possible.

The trilogy's third entry, War for the Planet of the Apes, releases on Blu-ray today (November 15) and to get a better understanding of what goes into the creation of the film's photo-realistic ape characters, I was invited to the Weta Digital studios in Wellington, New Zealand for a crash course in not only playing an ape, but animating one, too.

Getting into character

Weta Digital's motion capture studios are tucked away in a quiet, nondescript part of Wellington, not far from the capital city's hillside suburbs. Frodo Baggins would probably approve of the quaint nature of this major Hollywood player's surroundings.

After receiving a brief presentation from Dan Lemmon, Visual Effects Supervisor on War for the Planet of the Apes, I was whisked off to Weta's motion capture stages for the first part of my ape adventure.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Here, Lemmon would be directing me through a scene from the film. I would be walking alongside another ape through an enormous crowd scene filled with hundreds of simians in order to reach Caesar, Maurice and the rest of ape inner circle. Once there, I would deliver some kind improvised monologue to our ape leader and his confidants.

In reality, I'll be walking next to one other person on a mostly empty stage, dodging markers on the floor and delivering my speech to a tennis ball propped atop a big pole. The room is fitted-out with numerous infrared cameras, or 'passive markers', which work together to create a three-dimensional volume where our movements will be captured.

Before doing this, I'd need to be fitted for a 'mocap' (motion capture) suit, scanned into the computer, and then go through a short ape training session.

If you've ever seen any on-set footage of Serkis and his co-stars from the previous Apes films (Rise of the Planet of the Apes and Dawn of the Planet of the Apes), you'll know just how deeply, horrendously unflattering the mocap suit is. I proceeded to stuff myself into the ridiculously-tight outfit with some help from a Weta staff member.

Hideous and gray in color, there would be no hiding in this suit – all I could do was resign myself to the fact that I'd be spending the next couple of hours feeling incredibly uncomfortable.

The staffer explained that the suit needed to be tight to ensure that its various markers would be as close to my skin and as stationary as possible. If any of the markers were to dangle from the suit in any way, the motion capture process would be thrown off completely.

The markers, which consist of small silver balls, were then stuck on with Velcro patches around my chest, shoulders, elbows, wrists, legs and other areas on my body. For my fingers, Weta used some specially-made band-aids with silver balls sticking out of them.

Infrared light from the aforementioned cameras will be reflected from the markers and picked up by Weta's computers, which in turn will translate my movements and form the basis of my motion capture performance.

Suited up and ready to roll, I was then led to a room to be scanned and scaled into Weta's computers. This involved standing on a tall platform, moving my arms and legs around in a variety of ways and twisting my body around. The data from my scan was then applied to a 3D puppet which would act as my on-screen self.

Moving over to the stage once more, I met with motion capture actor Allan Henry, who proceeded to take me through the basics of ape movement. Though we wouldn't be using the more advanced arm extensions in this scene (useful for moving quickly in a traditional ape-like fashion), I still needed to be shown how to walk like an upright chimpanzee.

Henry explained that the apes in the film place most of their weight on their quadriceps, pushing their hips forward as they walk. It was also important to flow into each step and avoid any heavy stomping, as the apes in the film tend to move in a smooth and graceful manner. Perhaps thrown off by the spear I'd decided to use as a prop in the scene, this wasn't as easy as it sounded.

To my surprise, the team at Weta seemed pretty happy with my first take. Pacing is one of the most important aspects when walking through a shot with pre-determined camera movements, and it appeared that I'd at least nailed that part. In my mind, it didn't feel as though my steps were as fluid as they should be, though.

It was only upon viewing the scene on a nearby monitor that we noticed my ape partner hilariously walking straight through a horse – most likely because my own walking around the markers on the floor had steered him off the set path. A second take went a lot better (though we did notice some clipping through weapons) so we decided to move on.

Face time

Though the scene above was captured without the full head-mounted facial capture rig that's normally used for performances like these, I was given the opportunity to try one on and test it out – specifically, the exact rig Steve Zahn used in War of the Planet of the Apes while portraying the film's standout new character, Bad Ape.

"With each performer, we take a 3D scan of their head and the helmet is built to be an exact fit for their head," said David Luke, Motion Capture Tracking Supervisor at Weta. This ensures "a nice clean fit, so they don't get any pinch points on the helmet or anything."

Once I'd gotten over the shock of my huge head actually fitting inside Zahn's helmet, I noticed the camera pointed directly at my face. To my right was a small monitor sitting in the portrait position, which showed an extreme close-up of my face in a fisheye-like manner.

I was then instructed to move my head around, up, down, left and right. "You'll see that no matter how much you move your head around, your face is always bang in the center of the screen with all that head motion isolated from it," explained Luke. "That means that we can extract your facial motion easily without the body motion affecting it."

Seeing my face from the perspective of a camera pointed right at my nose was certainly confronting (ugh, remind me to pick up a blackhead removal mask) and would certainly be distracting if the monitor were present during a shoot. Luckily, this wouldn't be the case on set, so the actors can just focus on giving as truthful a performance as possible.

You may have noticed from the image above that there were no dots applied to my face in this particular instance. This was solely due to time constraints, though I was given a brief rundown of how the process works.

"For each performer, we have this vacuum-moulded mask, again based on a 3D scan of their face, and on the very first shoot day, we'll go through and mark up a network of dots on their faces," Luke stated.

According to Luke, each of the dots is used to mark the "key points on the face that help to describe the full range of facial poses, so all of these dots need to be visible from this camera at all times, and the mask ensures that each day, the dots are in the exact same place."

"So when we roll on a take, we will capture that information, and then we can take that media and, depending on what we're doing with it, we can either just use it for reference to 'key frame' animate against, or we can use it to help drive a puppet."

Facial animation masterclass

With the above information fresh in my mind, I headed over to the motion capture stage to get a hands-on tutorial on facial animation from Animation Supervisor Dennis Yoo.

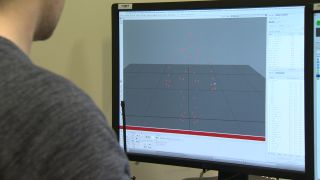

Using the facial animation software Maya by Autodesk, we kicked things off by placing a 3D model of the character Bad Ape right next to the face of Steve Zahn, the actor who played him in War for the Planet of the Apes. As the 3D model's body movements were already taken care of, our job was to match its facial expressions to that of Zahn.

With the CG model scaled to an acceptable size and angle, we could now begin the process of matching the position of his facial features to the raw footage of Zahn with dots all over his face.

Alongside the faces was a huge list encompassing all of the areas of Bad Ape's face that could be manually adjusted and tweaked. From here, the job involves moving through the scene, almost frame-by-frame, to ensure that the model's face matched the actor's as closely as possible.

We started off by making sure that Bad Ape's jaw was in the right position. Next, I adjusted his brow, cheeks, lips and mouth into positions that I felt were a close approximation of Zahn's own expressions using a number of sliders.

The sliders allow for 100 points of articulation, allowing the animator to really fine-tune each part of the ape's face. The trick is not to go overboard in either direction.

Once I was satisfied with that particular second of footage, it was time to hit 'play' on the scene to see it in motion. Given the nod of approval from Yoo, we continued on and repeated the process on a few other moments from the scene.

In working with Yoo and this software, I learned that a performance can still be tweaked at the facial animation stage. A very slight lowering of the inner brows, for example, can suddenly give Bad Ape a stern expression on his face.

"If you wanted to make him look sad, grab your inners [brows] and slide that forward, you'll see what happens to his facial expression." Following Yoo's instruction, I did just that. "It looks sad, doesn't it?" asked Yoo. He absolutely did, and with just a few mouse clicks, the scene suddenly took on a different feel.

Still, while minor adjustments like these are possible, it ultimately comes down to what the actor does on the day of shooting.

Evolution

The visual effects work in the Apes films has been stellar since the first picture in the trilogy (2011's Rise of the Planet of the Apes) but the team at Weta Digital has still gone to great lengths to evolve its technology, both in terms of digital effects and physical equipment, from film to film.

“We don’t tend to recycle tools – we tend to make them evolve, make them better and better or adjust them to the specific workflows that the movie might need," Alessandro Bonora, the team's Lead Facial Modeller, told us. “We don’t go ‘Oh the movie is done, let’s just create a new tool.’ We try to make things that work down the line – as in, we think always of the future." He continued, "If we make a tool right now, we’re thinking that in ten years, that tool is going to be quite different.”

The results of that approach certainly speak for themselves.

"The way [the apes] look, the way the fur renders, the rendering quality as well as the lighting, they're disarmingly realistic looking these days," said Animation Head of Department Daniel Barrett.

"We've had advances ourselves, and while our rigs are similar, and feel the same to use, they're actually much quicker," explained Barrett. "So we've had big speed increases, which makes for a happier animator, you know, the quicker you interact with your rigs, the more time you can spend looking for detail and getting that stuff right."

Visual Effects Supervisor Dan Lemmon was also keen to reiterate how Weta's mocap and animation technology has evolved over the course of the trilogy. "There's been a lot of advancement, but I think the biggest thing, is that a lot of the technology has gotten a lot better, certainly what we call 'rendering', which is the light simulation engine that basically makes the characters appear as the way that you see them in the movie," he explained.

"That engine has gotten better and we've ended up writing what we call our own 'ray tracer', which is something that allows us to simulate the way the light goes through the scene in a way that's a lot more realistic," said Lemmon. "You can visually see the difference between this last movie and the two that came before it."

He continued, "I think from 'Rise' to 'Dawn', we had a big jump in quality, and then from 'Dawn' to 'War' a big jump in quality as well, and that just comes down to rolling in these new techniques."

"But even more importantly, I think we as artists and craftspeople learned a lot along the way," said Lemmon. "So when we were making 'Rise', it was sort of uncharted territory for us – we were trying to figure out how we can make these ape characters connect with our human audience in a way that we understand what they're feeling and the emotions that they're communicating, and how much do we put human characteristics on to that ape face, and how much do we keep it more like an ape."

According to Lemmon, "It took a lot of trial and error to figure out where that line was and how to walk it."

"I think now, certainly on this last movie, we were able to create a whole bunch of new characters that were every bit as rich as the characters that we'd been building over the course of three movies, so that was pretty cool."

Making my ape debut

Having experienced an express version of what it's like to perform on a motion capture stage, I came away with a deeper understanding and even more respect for the accomplishments of Andy Serkis and the team at Weta Digital.

The physical demands of the job, as well as the commitment that goes into giving a powerful, emotional performance in such unusual conditions, cannot be overstated.

Likewise, the artistry and attention to detail shown by the visual effects department at Weta Digital is incredible. These professionals make magic happen on a daily basis, and with War for the Planet of the Apes, they've surpassed themselves once again.

And on that note, I'll leave you with the finished version of my ape performance, in which I get to hold a spear and crack a tech-themed joke. Though my face is not animated in the footage below, I like to think that the transformative power and burning intensity of my acting is undeniable. At the very least, you could call it a chimpressive debut.

- Earlier this year we saw how dead actors are being resurrected by VFX

- ILM condensed 40 years of VFX into a single video

War for the Planet of the Apes is out now to Blu-ray, DVD & Digital. Get it here on iTunes and here on Google Play.

Stephen primarily covers phones and entertainment for TechRadar's Australian team, and has written professionally across the categories of tech, film, television and gaming in both print and online for over a decade. He's obsessed with smartphones, televisions, consoles and gaming PCs, and has a deep-seated desire to consume all forms of media at the highest quality possible.

He's also likely to talk a person’s ear off at the mere mention of Android, cats, retro sneaker releases, travelling and physical media, such as vinyl and boutique Blu-ray releases. Right now, he's most excited about QD-OLED technology, The Batman and Hellblade 2: Senua's Saga.

Most Popular