The White House has rejected Intel's plans to increase chip production

The supply crunch is far from over

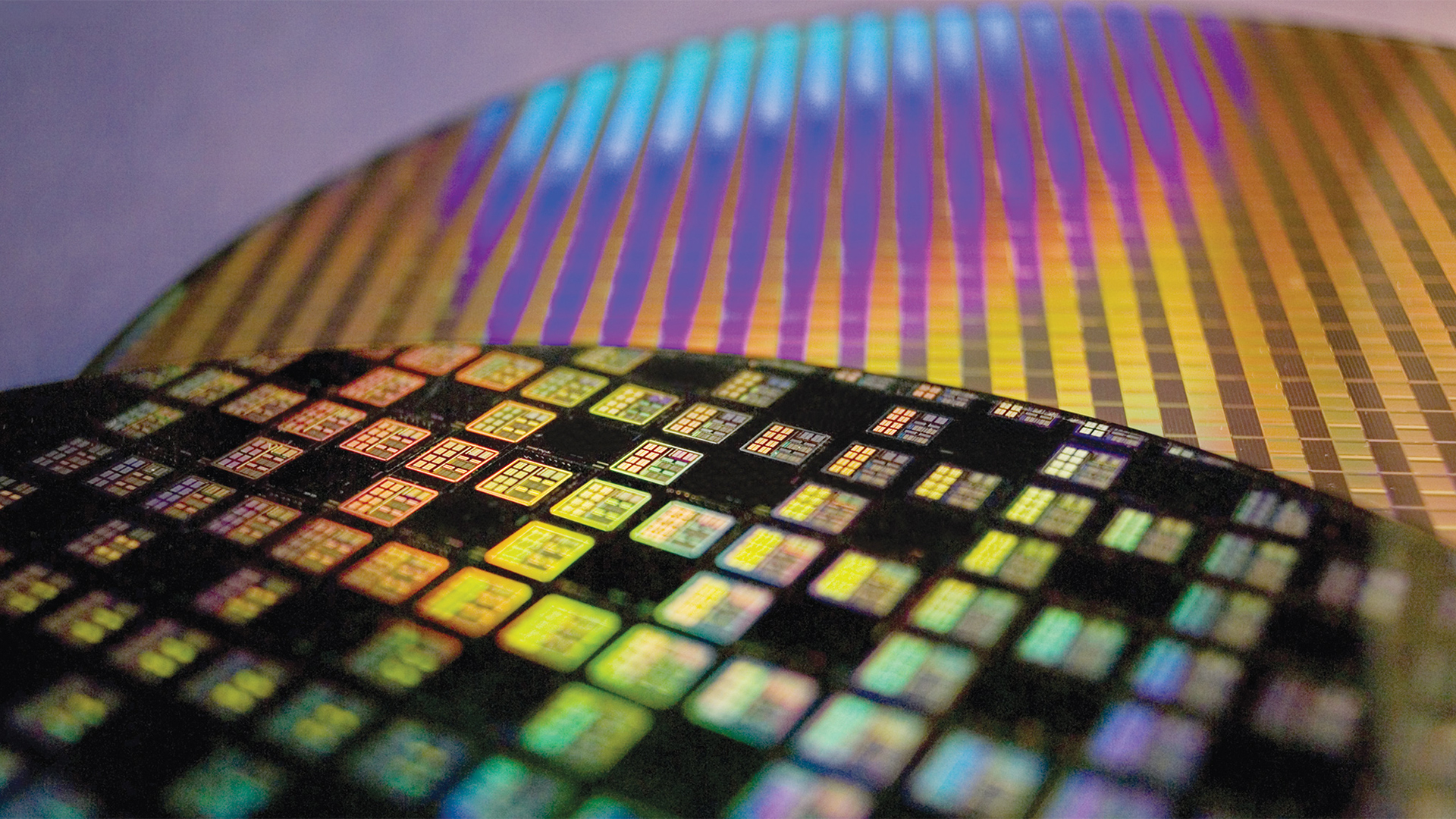

The US government has rejected Intel plans to use a Chinese factory to manufacture silicon wafers - meaning an ongoing chip shortage impacting everything from cars to computers won't be ending anytime soon.

Intel, the world's largest chipmaker, had sought federal assistance from the United States to increase current production output and additional research within the US, while also proposing to use a factory based in Chengdu to have something set up and running by late 2022. But the Biden administration has strongly discouraged the use of the Chinese factory, and Intel seems to be complying with the government's wishes, according to a report by Bloomberg, though the plans were discussed in private by anonymous individuals that have asked to not be identified.

While not directly connected, this comes not long after the White House announced it was considering restricting investments in China, with a representative claiming that the administration is “very focused on preventing China from using U.S. technologies, know-how and investment to develop state-of-the-art capabilities". This likely ties in with the ongoing national security concerns that have emerged since Chinese companies like Huawei and Xiaomi have been blacklisted from trading within the US.

Intel has since stated that “other solutions that will also help us meet the high demand for the semiconductors essential to innovation and the economy."

“Intel and the Biden administration share a goal to address the ongoing industrywide shortage of microchips, and we have explored a number of approaches with the U.S. government,” the company said. “Our focus is on the significant ongoing expansion of our existing semiconductor manufacturing operations and our plans to invest tens of billions of dollars in new wafer fabrication plants in the U.S. and Europe.”

With the current silicon shortage expected to last into 2023 by some industry experts, it's likely that we're going to have a hard time snagging in-demand tech such as PS5 consoles and Nvidia GeForce graphics cards for the foreseeable future.

Analysis: who made the right call?

Supply and demand is “the most extreme” it has ever been, according to CEO of semiconductor design firm Arm, Simon Segars, who warned the chip shortage may go on beyond Christmas 2022, with the wait for some silicon sitting at 60 weeks.

Are you a pro? Subscribe to our newsletter

Sign up to the TechRadar Pro newsletter to get all the top news, opinion, features and guidance your business needs to succeed!

“If you haven’t bought all your devices yet, you might be disappointed,” he said, speaking at Web Summit. “It has never been like this before.”

It would have been beneficial to lessen the pressure on the current market, with companies scrambling for available chips to such a degree that some customers likely won't get served until 2023. This affects everything from cars, to smart home tech, and is especially bad for high-demand products like game consoles and PC hardware in the run-up to Christmas.

The US government has every right to be cautious regarding overseas manufacturing in China, but the lack of a solution to the problem we're facing still stings. It feels unlikely that an immediate resolution can be found or made in time to alleviate the current production constraints, so without using outside manufacturing it's unlikely any home efforts will make a dent.

Currently, around 92% of all computer chips are manufactured in Taiwan, so regardless of if the US is planning to bring more production 'in-house', or looking to put stricter security measures into place before allowing additional production boosts, we're stuck playing the waiting game.

- We'll show you how to build a PC

Jess is a former TechRadar Computing writer, where she covered all aspects of Mac and PC hardware, including PC gaming and peripherals. She has been interviewed as an industry expert for the BBC, and while her educational background was in prosthetics and model-making, her true love is in tech and she has built numerous desktop computers over the last 10 years for gaming and content creation. Jess is now a journalist at The Verge.