The World Cup in motion: the infrastructure behind the greatest show on earth

From stadiums, fan zones and trains to mobile networks, sports science and VAR

Are you ready for a festival of football? From 14 June until 15 July 2018, 12 stadiums in 11 cities across Russia will host the 21st FIFA World Cup.

The first World Cup to be held in Europe since Germany in 2006, it's estimated that Russia 2018's infrastructure budget alone is over US$100 billion.

This is what it's being spent on.

To find out more about the Honor 10's incredible AI camera, watch this:

Russia 2018: stadiums and fan fests

There are 12 stadiums across 11 cities, with the final destined to be played at the 80,000 capacity Luzhniki Stadium in Moscow, which is also home to the Spartak Stadium. Brand new, purpose built-for-2018 stadia include the US$280 million Volgograd Arena (where England play Tunisia on 18 June), the US$290m Nizhny Novgorod Stadium (where England face Panama on 24 June), the US$330m Rostov Arena, the US$300 million Mordovia Arena in Saransk, the US$320 million Samara Arena, and the Saint Petersburg Stadium. The latter an cost eye-watering US$1.5 billion.

Others include the radically upgraded Ekaterinburg Arena, which is the furthest east of all the stadia, Sochi's Fisht Stadium that was used in the 2014 Winter Olympics, and the Kazan Arena in Kazan, which features the world’s biggest outdoor HD screen (4,030 square metres) on its outer west side.

Perhaps the oddest stadium, at least geographically, is the brand new US$300m Kaliningrad Stadium (where England will face Belgium on 28 June). Kaliningrad is a Russian enclave sandwiched between Poland and Lithuania, and completely cut-off from mainland Russia.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

The centre of each host city will also have a FIFA World Cup 2018 Fan Fest for those without tickets, with each big enough for between 15,000 and 40,000 people.

Russia 2018: travel infrastructure

The distances between the host cities are huge. For instance, Volgograd is a whopping 600 miles from Moscow. It's hoped that fans will either fly or take overnight trips on Russian Railways since organisers have laid-on 440,000 free seats for ticket holders with official Fan ID. Traveling between the host cities, 728 long-distance trains will ply 31 routes. Not surprisingly, all railway stations will have airport-style security.

FIFA estimates that this World Cup will generate over 2.1 million tonnes of carbon dioxide, made-up of international travel to Russia and travel between the host cities. FIFA will offset the 11.2% it directly controls, plus 2.9 tonnes per ticket holder traveling from abroad that signs-up. Why? 'To score goals for the climate', of course.

Russia 2018: broadcast TV infrastructure

Russia 2018 will be filmed in 4K HDR, but almost everyone around the world will watch it in Full HD. The host broadcast for Russia 2018, HBS, will have 37 cameras at each match, eight capable of dual UHD/HDR and 1080p/SDR output, and another eight delivering dual 1080p/HDR and 1080p/SDR output. There will also be eight super-slow-motion and two ultra-motion cameras, a cable-cam and a cineflex heli-cam, and some occasional 360-degree cameras to produce experimental content for VR headsets.

However, few countries around the world will use much of that; the UK doesn't have a broadcast infrastructure fit for 4K, so the BBC and ITV will both broadcast matches in 1080i. The BBC is putting some 4K HDR footage on its iPlayer service, which it’s done before using the HLG (Hybrid Log-Gamma) HDR format. This will be limited to certain televisions, however.

Thanks to Fox Sports, US fans will be able to watch 36 matches on Fox, and 28 on FS1, all in 4K HDR, and extra channels for watching on phones and tablets including a a stat channel, cable-cam channel, and a tactical-camera channel. That’s despite the US not having qualified for Russia 2018.

Russia 2018: refereeing and VAR infrastructure

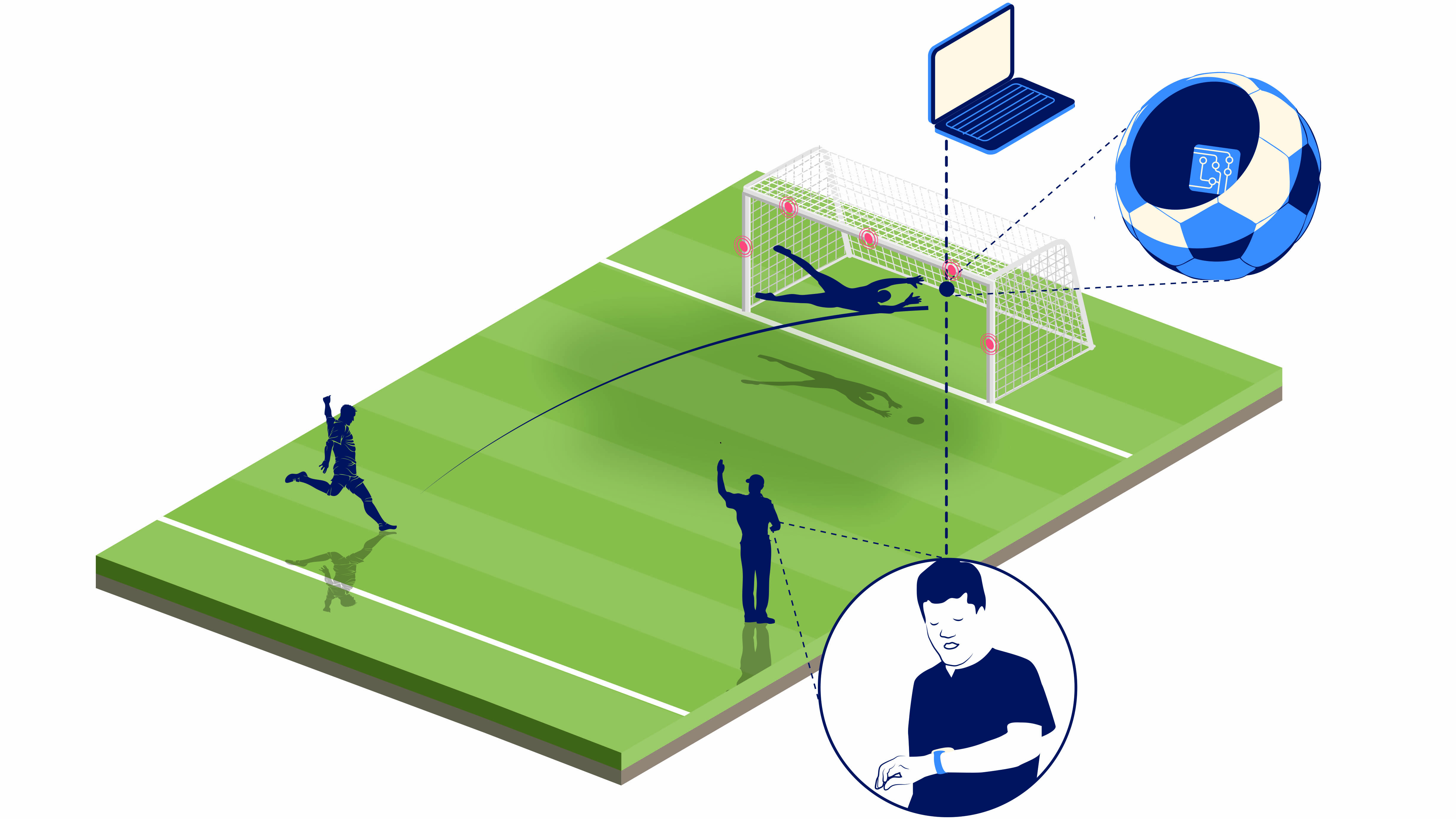

As well as the record 32 participating teams, the World Cup in Russia will host 36 referees and 63 assistant referees, representing 46 different countries. Thirteen of those will act solely as Video Assistant Referees (VAR), with the controversial technology to be used for the first time at a World Cup in Russia. Already tested in a handful of games in England, Germany and Italy, it's now official that every match will have a VAR plus three assistants.

The vast majority of the fans in the stadium will have their smartphones at the ready.

Warren Dumanski

Infrastructure-wise, it largely uses existing TV technology, with the extra match official sitting in the TV truck watching multiple slow-motion replays to help correct wrong decisions. VAR’s scope is limited to correcting 'clear and obvious mistakes', such as goals, penalties, direct red cards and mistaken identity, but the delays it creates make it very likely that VAR will be hugely controversial.

It’s all very easy to see what’s going on when you’re watching on TV, but VAR trials in the UK have resulted in very confused spectators. "The vast majority of the fans in the stadium will have their smartphones at the ready, looking to find out why that goal was disallowed, or what happened to get that player sent off," says Warren Dumanski, General Manager at telecom software company TEOCO.

"Unless the stadium’s communications capacity is being actively managed and flexed to allow the live audience to keep track of developments on their mobile, the stadium audience will remain frustrated." So how good are Russia's mobile networks?

Russia 2018: mobile network infrastructure

World Cups require massive bandwidth. The 2014 World Cup final at Rio's Maracanã stadium in Brazil broke all records for data sent by fans at the ground, with SindiTelebrasil reporting that mobile phone networks in the vicinity handled the equivalent of 2.6 million photos.

Although there will be free WiFi around stadiums, fans shouldn't expect much bandwidth from Russia’s four federal mobile networks when traveling around the country. "The Russian Federation was in the bottom 20 of 88 countries we analysed in 4G availability," says Kevin Fitchard, Lead Analyst at mobile analytics company OpenSignal, whose State of LTE report from February 2018 compared 4G performance in 88 countries. "Russia's average 4G download speed was 15.8 Mbps, a full megabit slower than the global LTE connection average of 16.9 Mbps." Compare that to the astonishing 40 Mbps average download speeds available in South Korea at the recent Winter Olympics.

Russia 2018: sports science infrastructure

Sports science infrastructure has been part of the game for a long time. All teams at the World Cup will use a FIFA-approved cameras-only platform called Electronic Performance & Tracking System (EPTS), with most teams adding Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems (MEMs) devices with GPS to the backs of players’ shirts. These devices track players' movements, collecting close to 1,000 data points per second to track the 'load' and intensity of movements by players.

For matches, one pitch-side coach and one analyst in the stands each get a tablet. The tablets show display live footage, replays, and basic player metrics, with the MEMs devices delivering rich data on heart-rate response and micro-movements. "Take the Zlatan Ibrahimovic goal from 2006 when he dribbled past five players to score, he never really travelled that far at any particular pace but that doesn't mean the movement wasn't demanding as he twisted and turned so much to break through a number of the opposition to score," says Rob Heyworth, a Sports Scientist at Catapult Sports, which which provides MEMs devices and analysis to 10 World Cup teams, including Argentina and Sweden, to use in training.

"The only way to capture this unique movement is to use inertial sensors attached to the players which collect data in 3D, 100 times per second to give us a clear image of the amount of work a player has done."

MEMs is seens as critical in World Cup where matches are played with only a three or four day turnaround to control each player's 'load' (and, hence, their tiredness) and keep them injury-free.

Russia 2018: security and cybersecurity

In case you hadn't noticed, there's a kinda Cold War-esque political tension thing going on between Russia and 'The West'. There has also been some concern over fans' safety, but if the Winter Olympics in Sochi in 2014 is anything to go by, security will be very tight. Fearing any kind of trouble – from rioting to terrorism – the Russian government has already banned drones near World Cup stadiums, and will close roads around controlled zones for fans. However, cybersecurity could still be an issue.

It’s vitally important that attendees and players alike go to the games with a strong level of cyber-awareness.

Caitlin Huey

However, there’s more to worry about than physical security. “Cyber threats also pose a significant risk to the games and should be a keen focus for organisers, teams and attendees alike," says Caitlin Huey, Senior Threat Intelligence Analyst at EclecticIQ. Phishing, website defacement, targeted malware campaigns and rogue wireless networks are all expected (there were targeted campaigns at the 2014 World Cup), but individual fans also need to be aware.

"Cybercriminals may attempt to steal personally identifiable information, banking and credit card information, deface or disrupt a local government or event sponsors' web presence, and more," says Huey. "It’s vitally important that attendees and players alike go to the games with a strong level of cyber-awareness, and practice cyber-security best practices including avoiding public or free WiFi, ignoring unsolicited emails and SMS messages, and enabling device encryption.”

Will Russia 2018 be the biggest World Cup ever? Yes, but not for long; by 2026 there will be 48 teams competing rather than the current 32 teams, with FIFA considering bringing that expansion forward to Qatar 2022. Either way, for football fans Russia 2018’s US$100 billion bill will be money well spent.

(Main image: chain45154, Getty Images)

TechRadar's World Cup coverage is brought to you in association with Honor.

Jamie is a freelance tech, travel and space journalist based in the UK. He’s been writing regularly for Techradar since it was launched in 2008 and also writes regularly for Forbes, The Telegraph, the South China Morning Post, Sky & Telescope and the Sky At Night magazine as well as other Future titles T3, Digital Camera World, All About Space and Space.com. He also edits two of his own websites, TravGear.com and WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com that reflect his obsession with travel gear and solar eclipse travel. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners (Springer, 2015),