Are bad hardware and games ruining virtual reality?

Some say smartphone-based systems could kill-off the entire concept, others disagree

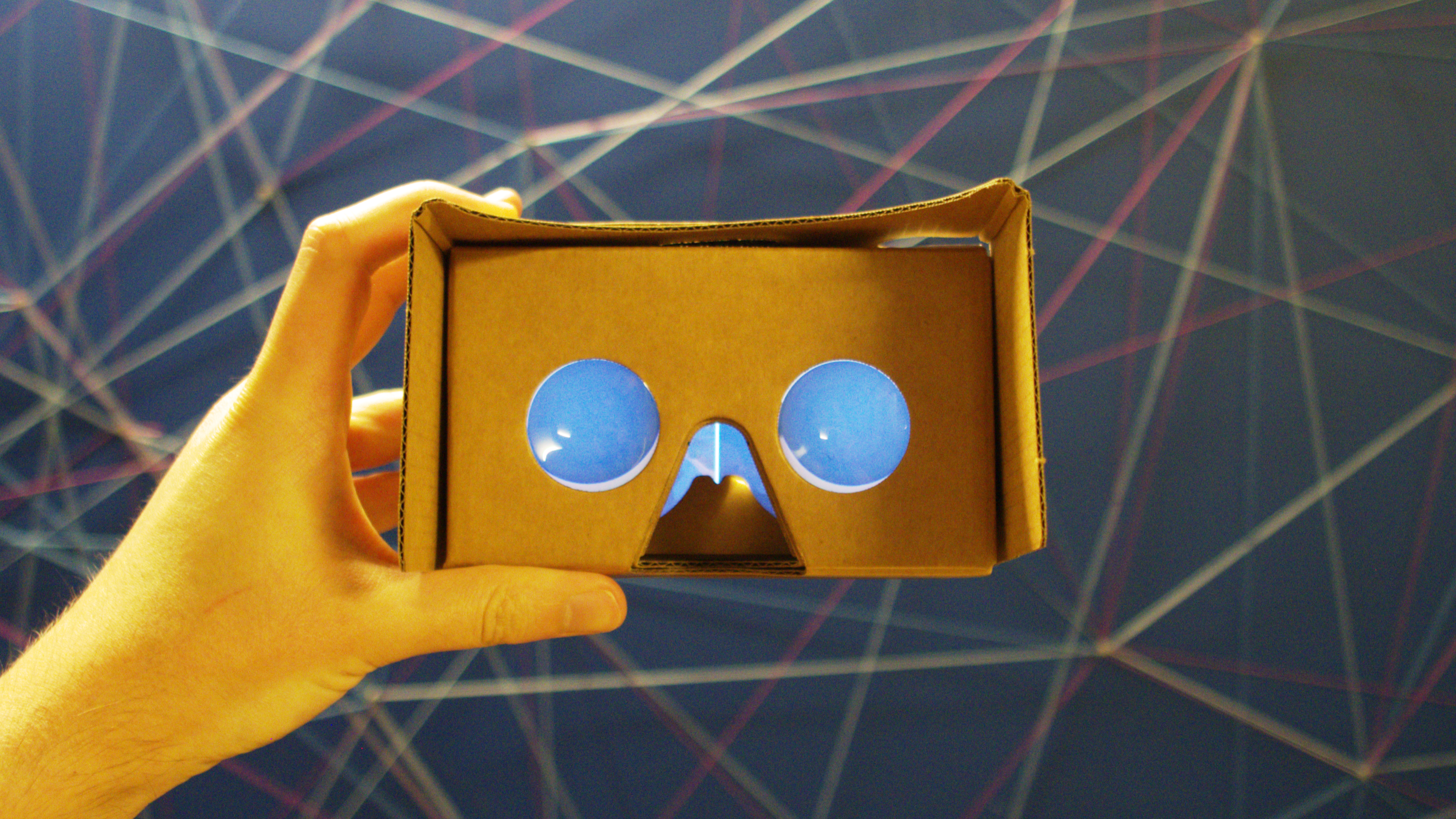

After decades of hype, is virtual reality being strangled at birth? Dedicated headsets like Oculus Rift, HTC Vive and Sony PlayStation VR look super-exciting, but most people are getting their first taste of VR as an online 360 video via something a lot more rudimentary.

A survey in July by European IT market analysis company Context revealed that Sony PlayStation VR is the headset UK consumers are most likely to purchase, but Google Cardboard is the one they've tried out the most.

Are 'ad hoc' VR viewers and smartphone-based systems like Google Cardboard and Samsung Gear VR the only way VR will catch-on, or are they ruining everything? We've asked a few experts to weigh-in on the debate.

The three types of VR

Let's go over the basics first. Not all VR content and hardware is equal, but it's important to understand the three different flavours; computer-generated environments, recorded 360 video, and a mixture of the two. Even 360 video can come in two forms, monoscopic and stereoscopic, which give different levels of immersion.

"In mono you can see content all around you, while with stereo you get depth perception, which offers greater immersion and placement inside an environment," says Alex Mahon, CEO at VR software company The Foundry. "Currently, this only lets you look around – it's a passive experience that you watch."

This is what Google Cardboard and Samsung Gear VR deal in, and some think that this should be called 'immersive video' rather than associated with VR, which adds many more dimensions.

"In a computer generated VR environment you can add interactive elements, a bit like a game," adds Mahon.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

The role of 'ad hoc' VR viewers

"VR viewers like Cardboard and, to a lesser extent Gear VR, offer a way for casual users to get a small insight into the one aspect of the gamut of VR technologies, that of the display," says Warren Lester, Products Manager – Engineering at Vicon. "The danger is that these devices propagate misconceptions about VR in general."

After all, the viewers that push a 'VR lite' experience are all about accessibility, not quality. "Cardboard and platforms such as YouTube 360 and Facebook 360 have made VR accessible, and an experience that you can share with others," says Mahon. "The availability of Cardboard and GearVR has turned VR from a niche technology to something everyone can get their hands on and explore."

That's true, but Google Cardboard is 360-degree film. No more, no less.

"There is a place for both 360 degree video and VR, and they share some technologies, but they're like chalk and cheese," says Lester.

So could Google Cardboard confuse people?

"There's the potential for it to confuse people who haven't yet seen full on head-tracking VR," says Jason Kingsley OBE, games developer and founder of Rebellion games. "If people try Google Cardboard and are underwhelmed, we have to be careful they don't assume 'that's VR', and write it off."

However, Kingsley thinks that Samsung Gear VR's ongoing partnership with Oculus, as well as the growth of Google's DayDream, will mean that the baseline of VR content will constantly increase and improve. Samsung's Gear VR is a little different as a proposition, positioned somewhere between Cardboard and 'proper' VR hardware.

"The Samsung Gear VR is interesting as it offers the potential of far wider reach than the tethered HTC and Oculus, yet can still provide an impactful experience, which can be either at home or at retail," says Matt Gee, Head of Digital Transformation, nowlab, Isobar.

However, Kingsley thinks that these mobile viewers are a world apart from dedicated game platform tech, saying: "the lower prices of the likes of Gear VR means they can't yet match the screen fidelity and more advanced features."

The importance of quality

It's yet to hit the mainstream, but we're entering a crucial time for VR in terms of getting people excited. "Given the immersive and immediate nature of VR, users are far more unforgiving of bad experiences," says Kingsley. "If the frame rate isn't up to scratch, or if the alignment is off even slightly, your brain will tell you, so offering experiences of the highest quality is an absolute must."

For Kingsley – as it is for many other VR enthusiasts – that means PC, or console-based VR will always be better than a smartphone, purely because of the increased power.

"Developers can create more ambitious projects, not just visually, but also in terms of gameplay, interaction, audio, and so on," he says, pointing out that the audience that owns a PS4 or gaming PC invests far more money in games than Android phone owners.

"It makes sense to concentrate VR development on those platforms, even if cheaper mobile VR headsets become more widespread," he says.

Not everyone agrees that high-power VR is necessarily better than smartphone-based systems, however.

"At this point I do not believe that Oculus Rift or HTC Vive offer a particularly different experience," says Dmitry Bagrov, UK MD of global technology consulting firm DataArt. "There is nothing especially different about these platforms, and right now they are not offering much of a 'wow' factor."

But Bagrov does think that the game-changer will be the Sony's PlayStation VR, which the company plans on releasing on October 13.

"Exclusive content is the key here, and as Sony has the capacity to create this, the competition between smartphone reliant and purpose built systems will really start to kick-off."

The spread of smartphone VR

While most agree that VR consoles and headsets can offer much the best VR experiences, it's the smartphone that remains in pole position.

"Smartphone VR will become the widest used VR medium in time, especially as viewing becomes more integrated into handsets," says Gee. "The accessibility of entry-level VR through Cardboard and smartphones will produce a dearth of throwaway content, but the significant levels of investment and involvement from the tech giants, Hollywood studios, broadcasters and brands suggest the medium is here to stay."

There's also a feeling that smartphones, while not the ideal hardware for VR as it stands, will vastly improve.

"VR technology today is really not very complex – it's currently driven by price-performance more than deep technology innovation – so there is much room for improvement," says Mahon, who doesn't believe that smartphone-based VR is a threat to the 'format' as a whole.

"Poor experiences aren't yet holding back VR, because the audience is still quite limited, and most people are experiencing VR for the first time," she says.

"As early adopters, many are interested in a deeper level than just being entertained."

Navigating the virtual rapids

VR is currently something of a minefield, a jigsaw of different sources and various hardware.

"What we need with VR right now is an iPhone based approach – high quality content delivered in a closed ecosystem," says Bagrov. "Gaming with VR will be huge, as will be graphic entertainment (no need to elaborate), simply because the money and demand will be there," he says adding that Sony could be the real winners.

"Sony will be to VR what Apple was to smartphones."

No pressure, then.

Jamie is a freelance tech, travel and space journalist based in the UK. He’s been writing regularly for Techradar since it was launched in 2008 and also writes regularly for Forbes, The Telegraph, the South China Morning Post, Sky & Telescope and the Sky At Night magazine as well as other Future titles T3, Digital Camera World, All About Space and Space.com. He also edits two of his own websites, TravGear.com and WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com that reflect his obsession with travel gear and solar eclipse travel. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners (Springer, 2015),