Apple vs Google: The battle of the beacons

The tech world now has two kinds of 'lighthouses'

Smartphones don't just connect to nearby cell phone towers. Proximity beacon technology has been around a few years in the form of Apple's iBeacon, which allows an iPhone or iPad to connect to objects – called beacons – using Bluetooth.

Retailers, museums, sports stadiums and anywhere else with large numbers of smartphone users can now use beacons to provide hyper-local information down to the exact aisle, exhibit, or seat. Airports, zoos, concert halls and shopping malls are now being fitted with Bluetooth-powered beacons that let smartphones pick up adverts, notifications, and even navigate indoors. However, since its launch in 2013, the iBeacon infrastructure has been built up with only iOS users in mind. Step forward Google's Eddystone.

What are proximity beacons?

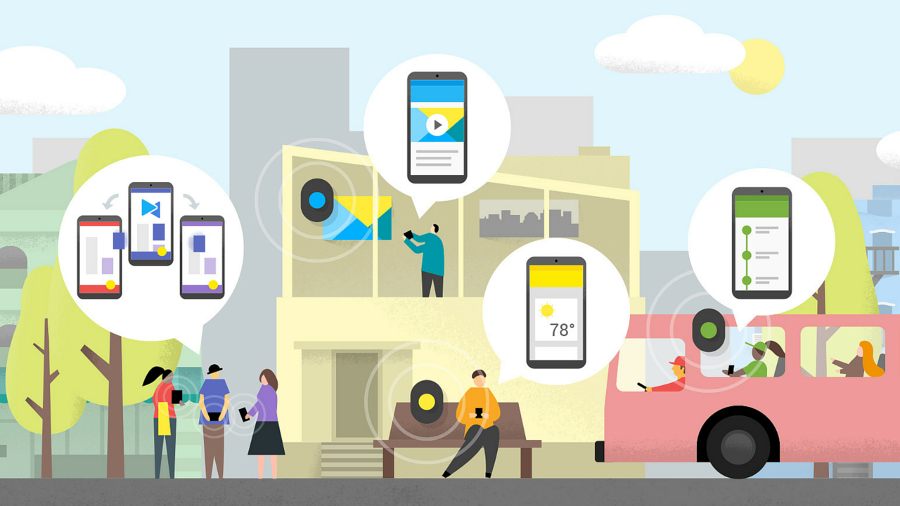

A beacon is a miniaturised Bluetooth radio that can be placed almost anywhere. Google wants us to think of beacons as lighthouses (for some reason Eddystone is named after a lighthouse in Cornwall, England), helping us navigate with precise location and context.

"A beacon can label a bus stop so your phone knows to have your ticket ready, or a museum app can provide background on the exhibit you're standing in front of," writes Google in a blog post. Such environments could have a fleet of beacons ready to push information to a smartphone when it passes by. Eddystone and iBeacon use Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE), a wireless communication standard that can broadcast uniquely identifiable messages when in 'advertising mode'.

What is Eddystone?

Crucially, Eddystone is much more than just iBeacon for Android. It's an open format, available on GitHub under the open-source Apache v2.0 license. Not only can it be used to communicate with both Android and iOS devices, but Eddystone can work with web browsers as well as apps.

Eddystone-ready beacons can broadcast URLs, so if you're in a museum you can get notifications straight to your phone without first having to download that museum's custom app. However, whether it will be able to instruct, say, the native Passbook app on an iPhone to get a plane ticket ready when you arrive at the airport remains unclear.

How does Eddystone compare to iBeacon?

Both Eddystone and iBeacon have a similar goal – contextual information – and both rely on BLE tech. But as well as being open, extensible and interoperable, Eddystone is designed to go much further than iBeacon.

Are you a pro? Subscribe to our newsletter

Sign up to the TechRadar Pro newsletter to get all the top news, opinion, features and guidance your business needs to succeed!

"We've learned a lot about the needs and the limitations of existing beacon technology," says Google, "so we set out to build a new class of beacons that addresses real-life use-cases, cross-platform support, and security." Security is everything for Eddystone, which includes a feature called Ephemeral Identifiers (EIDs). These EIDs require authorised clients to decode them, and regularly change. Google suggests that EIDs will make it possible for people to securely locate their beacon-laden luggage, or find lost keys.

Eddystone also promotes better location, not just allowing smartphones to communicate with nearby beacons, but to translate into more useful, real-world measurements; Eddystone can talk in latitude and longitude, too. That could make it useful in wild areas and national parks where hikers and walkers struggle with phone signals, at least for sporadic events (as such it seems a marketing shoe-in for the Brecon Beacons National Park).

Google has also promised that Eddystone will integrate into Google Maps and Google Now to offer better, more targeted and faster access to real-time public transport schedules – something that's already being trialled in Portland, Oregon.

- 1

- 2

Current page: Introduction and Eddystone vs iBeacon

Next Page Global picture and crowd-sourced dataJamie is a freelance tech, travel and space journalist based in the UK. He’s been writing regularly for Techradar since it was launched in 2008 and also writes regularly for Forbes, The Telegraph, the South China Morning Post, Sky & Telescope and the Sky At Night magazine as well as other Future titles T3, Digital Camera World, All About Space and Space.com. He also edits two of his own websites, TravGear.com and WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com that reflect his obsession with travel gear and solar eclipse travel. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners (Springer, 2015),