The rise of the internet has made generating rumours easy. Post the right thing to the right forum and the baying masses will do your work for you.

There's no burden of proof any more. If it sounds true, it is. Automatically.

Take Google's recent foray into the undersea world. When it added seabed geography to its Google Earth global mapping software early in 2009, a few plucky users spotted a section of crisscrossed lines off the coast of the Canary Islands, just like the embossed road layout of a modern American city (or a particularly wet Milton Keynes).

The strange find was close enough to Plato's suggested site for Atlantis for mythology fans to immediately leap upon it as evidence of a startling breakthrough.

Atlantis had finally been found! In reality, this was an artefact of Google's sonar-based depth scanning technology, and even The Sun managed to rein in its excitement enough to explain that it was all a big mix up.

We're watching you

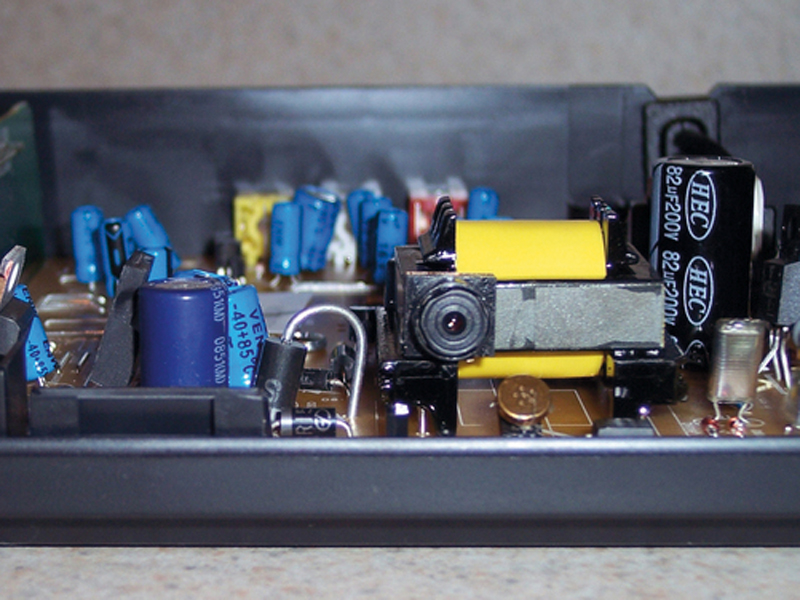

Americans have recently been making the enforced switch to digital terrestrial TV, buying government-subsidised DTV converters in the process. One software engineer, 28-year-old Adam Chronister, was inspired by conspiracy rumours to open up his new DTV box.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

He made a YouTube video documenting his horrifying finds – a camera and microphone, pointing directly into his front room. Is the US government using the DTV conversion process to spy on every American citizen? No.

Chronister took the camera and microphone from an old mobile phone and attached them to his DTV box with hot glue. But the hoax video made its way round forums, blogs and even the website of a popular conspiracy radio show before Chronister came forward and owned up.

One of the main reasons these rumours stick is plausibility. Why wouldn't there be a camera in a DTV box, installed for some future interactive service not yet announced? Camera interaction is becoming commonplace in computing, after all.

Atlantis could easily have been designed in the modern American style of a floating island in the middle of nowhere, later sunk 3.5 miles into the sea, remaining undiscovered until some canny observer found it on Google Earth. Well, OK, perhaps not that one.

Damaging reputations

This plausibility is what makes it so easy to generate and spread rumours online. When highly trafficked blogs post unsourced rumours – as TechCrunch did when it erroneously announced that Last.fm was sharing its user data with the RIAA – people tend to listen, rightly or wrongly. The effects can be truly devastating.

Last.fm systems architect Russ Garrett was forced to make a statement on the site's forums, stating "We've never had any request for such data by anyone, and if we did we wouldn't consent to it. That goes against everything that we stand for. As far as I'm concerned, TechCrunch have made this whole story up."

As newspapers close and the media consolidates, these incidents become more commonplace. Happily, though, the mainstream media is beginning to get a grip: The Sun was cautious when it ran the Atlantis story, and the conspiracy enthusiast DJ Alex Jones publicly shunned the DTV hoax on his radio program.

Only the news small fry, clamouring for traffic, were desperate enough to publish straight rumour as fact.

The best way to avoid falling prey to rumours is this: pick your sources carefully. And then cross-reference them. Twice.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

First published in PC Plus Issue 281