Natural language processing: is this the end of the written word?

How speech recognition is powering a spoken-word revolution

To some the Spike Jonze movie Her was excruciating, to others it was a glimpse into the future, but imagine if the film's personal assistant Samantha had suddenly uttered to Theodore: "Sorry, I didn't catch that?" It would have killed the romance dead.

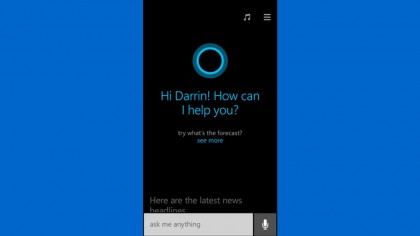

Siri and Google Now's conversational styles are nowhere near Samantha's, but their development is part of a movement that is threatening to eclipse the written word. Our handwriting has never been worse, typing on a keyboard is beginning to feel archaic and even constantly tapping out text messages and web search terms is likely to bring on finger cramps and sore hands.

With iOS devices now allowing the sending of voice messages and predictions for self-driving cars and voice-activated doors, lights and elevators (cue the internet of things), it's clear that the future will be spoken, not written.

The technology behind this shift in how we interact with our surroundings is natural language processing, a technology that enables computers to understand the meaning of our words and recognise the habits of our speech.

Where will we see natural language processing first?

As well as Siri and Google Now, you may already have used it on the Xbox One and the Samsung UE65HU8500

but so far voice recognition has revolved around a very small list of phrases and words. A proper conversation this is not. "Magic words have caused these technologies to rely on structured menu systems in which voice command simply replaces traditional inputs," says Charles Dawes, Global Strategic Accounts Director at Rovi. "These do not provide a satisfactory experience, forcing users to learn how to talk to the device and causing speech to become stilted and unnatural."

Automatic speech recognition systems on TVs have so far relied on built-in microphones that could be some way from the viewer, though mosts are moving to apps. "The prevalence of smartphones and tablets offers operators the opportunity to sidestep this issue by enabling search and recommendations for the TV via the second screen," says Dawes. "The development of these devices has boomed, and the processing power offered by most on the market provides an ample base upon which to build conversation capabilities."

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

But there are many other places we're already seeing natural language engines used. Barclays Wealth uses it to verify an account holder, airline JetBlue is using intelligent voice advertising, and Ford is using natural language for drivers to control in-car systems such as the phone, music, temperature, navigation and traffic updates.

How does natural language processing work?

Once it's recognised what someone has said, it's then all about context, and disambiguating similar terms. "A viewer could say 'what time is the City game on tonight?', and voice technology would have to make a decision about the context – football – and the preference of the user based on their history. Do they support Norwich City or Manchester City?" says Dawes. "The technology must also be able to deal with sudden changes. For example, it must recognise that if the same viewer then asks 'are there any thrillers on tonight?' they are searching outside the context of sports."

Jamie is a freelance tech, travel and space journalist based in the UK. He’s been writing regularly for Techradar since it was launched in 2008 and also writes regularly for Forbes, The Telegraph, the South China Morning Post, Sky & Telescope and the Sky At Night magazine as well as other Future titles T3, Digital Camera World, All About Space and Space.com. He also edits two of his own websites, TravGear.com and WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com that reflect his obsession with travel gear and solar eclipse travel. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners (Springer, 2015),