The Screenfridge was developed by Data Vision Europe in association with ICL and Electrolux. The press release unwittingly provides several reasons why it didn't take off.

"The fridges will be market tested within the next six months and could go on sale by next year," Data Vision Europe wrote. In fact it took a bit longer than that: the Screenfridge finally went on sale in 2006, not 2000.

"It is estimated they will cost £700 to £800 more than a standard fridge/freezer," the press release continued. The Screenfridge was £5,000.

"To cap it all, the proud owner can then put his or her feet up and watch TV on it," the blurb trumpeted. The Screenfridge had a 15in display stuck to the front of a fridge. It's hardly a Sony Bravia.

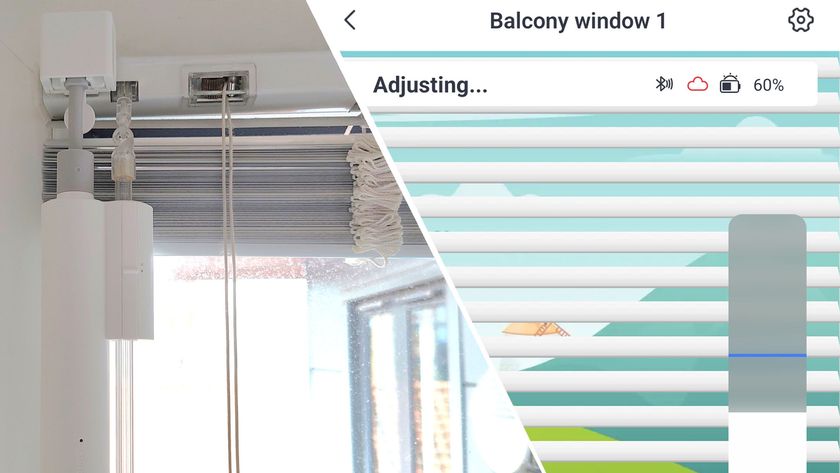

Our favourite bit, however, wasn't in the press release: it was when The Daily Telegraph was shown around the Screenfridge showhome in Stockholm, a state-of-the-art development where the front door could be opened or locked remotely, blinds automatically shielded the inhabitants from the sun and motion detectors turned off the lights and air conditioning whenever they detected that nobody was at home.

"This is not about gadgets for gadgets' sake," project manager Mikael Klein told the newspaper – before admitting that "people do not want things like Screenfridges per se." As The Daily Telegraph pointed out, the technology wasn't exactly affordable either.

"The price of all the appliances, sensors and remote control devices has not been set yet, but Mr Klein estimated that it would double the cost of the £280,000 house." That's a lot of money to spare the drudgery of closing curtains, switching off lights and writing a shopping list before you go to Tesco.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

So, will the automated home remain in the same category as jetpacks, flying cars and living on the moon – ideas that fire kids' imaginations but never become reality? Perhaps not.

However, there are several problems that automation needs to address if we're ever going to welcome it into our homes.

High-tech home time

There are several reasons why automated homes aren't in every suburban street. The first and most obvious one is money: cutting-edge kit costs a fortune.

For example, Electrolux's Trilobite 2 robot vacuum cleaner costs around £775, while Husqvarna's robot lawn mower, the Automower, has an RRP of £1,499. When you can buy a decent Dyson mower for around £130 and a top-end Flymo costs £115, then you need to be exceptionally cash-rich and time-poor to even consider buying a robot version.

ROBO-VACUUM: The second-generation Trilobite from Electrolux is still thwarted by stairs

Price isn't the only issue, though. Robot vacuum cleaners, like Daleks, can't climb stairs – and it seems that they're not too great at the vacuuming bit either. In 2004, the Wall Street Journal reviewed the first Trilobite and two other robot vacuums and the verdict was summed up in the headline: "The only thing latest robot vacuums cannot do is clean."

Of course, the technology has advanced since then, but not by much: in 2008, Register Hardware reviewed the iRobot Roomba 560 robotic vacuum cleaner.

"Roomba certainly didn't pass the wife acceptance test," Lewis Page wrote. "The machine takes its time, going over every bit of floor repeatedly before it's satisfied, but the results after it eventually gives up are frankly unimpressive. In some rooms, the time taken to get rugs and so on out of the machine's way and put them back afterwards meant that an ordinary vacuum actually demanded less user time as well as doing a much better job."

The conclusion? "As a plastic pal that's fun to be with, the 560 is great – as a way of cleaning floors, not so much."

Another issue with intelligent appliances is that it's easy to overcomplicate things. For example, our washing machine is computerised: it has sensors to judge the weight of the load and to adjust washing programmes accordingly. Sounds good? Every third wash, the sensors decide that the load isn't balanced properly and the machine goes on strike, flashing up an error message and beeping.

Our last machine was as dumb as rocks, but it never got in a huff at our laundry-loading skills – and we never had to reboot it like a badly behaved PC. Adding automation adds cost and complexity, and it's often hard to see the benefit.

Take the idea of the intelligent fridge that does its own shopping. You'd need to enlist the supermarkets, decide on a standard way for fridges to place shopping orders – which isn't very likely to happen, not least because automation removes the opportunities for the up-selling, cross-selling and bundling that supermarket websites are so good at – and train your fridge.

'Aaagh! That hummus is awful!' you cry, hurling the pot into the bin. 'We're out of hummus!' the fridge happily exclaims, ordering more from Tesco.

Current page: The cost of automation

Prev Page Why don't we all have automated homes? Next Page Why connected homes are more realistic