Weren't we supposed to have 3D printers everywhere by now?

One day our 3D prints will come

Remember 3D printing? It was supposed to be massive by now. The technology would improve so quickly, and prices would fall so sharply, that we'd soon be sitting around printing guns, pirate copies of cars and extra legs.

But we don't all have 3D printers churning out all manner of household goods, and there aren't plentiful websites giving us blueprints to make the things we need. However, 3D printing is changing the world – it's just doing it in places you might not expect.

3D? Over my dead body

A funeral parlour isn't the most obvious place for a 3D printer, but the Longhua funeral parlour in Shanghai offers a very unusual service: 3D printing of body parts for damaged or disfigured corpses.

It's believed to be the first such service in China, and the cost of a replacement face is 4,000 to 5,000 yuan (around £450-£540, $650-$780, or AU$890-AU$1,070). It sounds weird, but it's a valuable service for grieving families who want an open-casket funeral.

But it's the living who really benefit from 3D printing: in February, an Australian man became the first person to have 3D-printed vertebrae installed.

He had a tumour in his neck that would have rendered him paraplegic, but replacing the affected vertebrae with bone from elsewhere in his body would be exceptionally difficult and dangerous.

The solution: a world-first, with 3D-printed vertebrae providing a perfect fit.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

As neurosurgeon Ralph Mobbs put it: "It was as if someone had switched on a light and said 'crikey, if this isn't the future, well then I don't know what is'."

Heads, shoulders, knees and toes

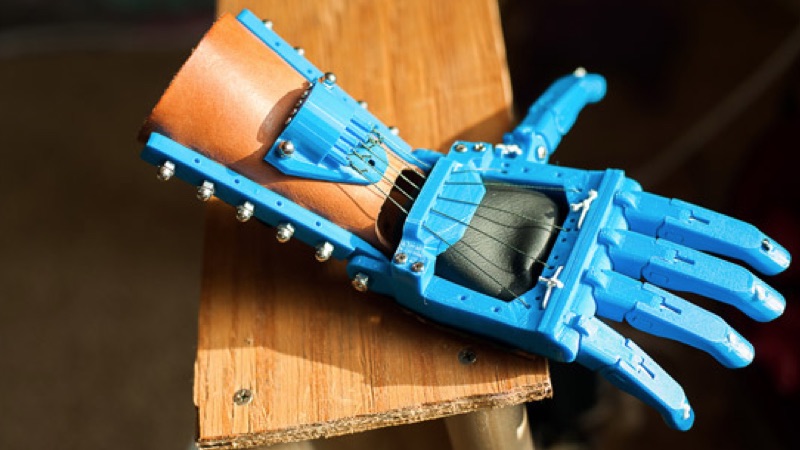

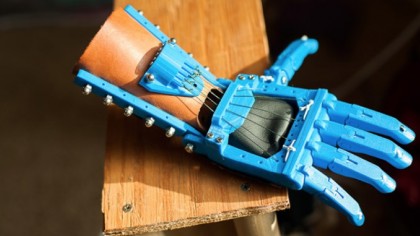

3D-printed prosthetics are transforming lives around the world, not least because they make such prosthetics much cheaper.

As professor John Schull of Rochester Institute of Technology told PBS: "A prosthetic arm these days costs about $40,000. One in 2,000 kids are born with some kind of an arm or hand abnormality.

"They don't get prosthetics because it makes no sense to spend $40,000 on something they're going to outgrow in a year. With a 3D printer, we can start making these things almost for nothing. Instead of $40,000, you can do it with about $10 or $20 worth of plastic.

" ...it's not as sturdy as a $40,000 titanium artificial arm. On the other hand, if you outgrow it or break it, you can make another."

The next step is to have 3D-printed organs for transplants, and that's getting closer too: also in February, US researchers published details of a 3D 'bioprinter' that can print muscle, cartilage and bone.

It's not quite ready for human use – so far the tests, while successful, have been on animal subjects – but the potential is enormous.

3D printers can save lives indirectly too. In Nepal, the aid organisation Field Ready used its 3D printer to make parts for water systems, ensuring safe water and sanitation for 200 people displaced by earthquakes.

Field Ready's engineering adviser Andrew Lamb told The Guardian: "It's that process of identifying the need, doing the design and then printing it out and fitting it out – and doing all that in less than 12 hours in a remote area. It's a pretty important step forward, I think, for the use of this kind of technology."

Lamb believes that relief agencies and other non-governmental bodies will soon be taking 3D printers into disaster areas as a matter of course, making everything from water fittings to spare parts for the Toyota 4x4s so many people rely upon.

That's all very impressive, but when will we be able to 3D-print Teslas via the Pirate Bay?

Where are the pirate printers?

Piracy has often been described as 3D printing's killer app, with 3D printers doing to manufacturing what Napster and the MP3 did to CDs – and the possibilities become more outlandish by the day.

Writer, broadcaster, musician and kitchen gadget obsessive Carrie Marshall has been writing about tech since 1998, contributing sage advice and odd opinions to all kinds of magazines and websites as well as writing more than a dozen books. Her memoir, Carrie Kills A Man, is on sale now and her next book, about pop music, is out in 2025. She is the singer in Glaswegian rock band Unquiet Mind.