How the Myanmar VPN ban is plunging citizens into online darkness

People are reportedly facing arrests and fines for using VPNs

People in Myanmar have been left in digital darkness as the military junta banned VPN usage. The move comes as yet another way to control the flow of information within the country.

According to local media, mobile networks, and internet service providers, the military Junta has enforced the ban since the end of May—the Associated Press reported. Citizens lamented that some of the best VPN services stopped working, failing to connect them to censored social media platforms, including Facebook and WhatsApp, as well as other popular websites.

Soldiers have reportedly inspected the phones of random pedestrians on the lookout for illegal VPN apps, too. Some residents suffered fines of up to 3 million kyats ($1380), or arrests if they couldn't pay, across some major cities just for having a VPN installed.

"For the last three years, the military has sought the latest technology and tools to tighten its control over peopleʼs access to information," Wai Phyo Myint, Asia Pacific Policy Analyst at Access Now, an international human rights organization, told me. "This latest VPN ban has a severe impact on access to the internet for people in Myanmar and it is one of the strictest restrictions we’ve ever seen; very few countries in the world have ever experienced restrictions on such extreme scale and scope."

An information crackdown

Since the military junta seized power in 2021, people in Myanmar have been suffering attacks both in the digital and real world.

Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, WhatsApp, and similar social networks are blocked. Independent news sites or online projects like Wikipedia are also censored. Authorities regularly use internet shutdown as a weapon, too. Access Now reported that 11 of the 37 internet shutdowns enforced in 2023 were "tied to documented grave human rights abuses or war crimes." All this takes place with the ongoing conflict between the military and rebel groups flaring up in the background.

A VPN, short for virtual private network, is security software that encrypts internet connections and spoofs IP address locations. The latter skill is exactly what you need to bypass online geo-restrictions applied to websites and apps. It's not surprising that, in such a disconnected environment, VPNs have become the main source of news for the Burmese people, with authorities trying hard to strap them from this tool.

Are you a pro? Subscribe to our newsletter

Sign up to the TechRadar Pro newsletter to get all the top news, opinion, features and guidance your business needs to succeed!

Wai Phyo Myint explains that, since May 30, many VPNs, including popular ones such as Psiphon and NordVPN, have been banned. "It seems the military is keen on blocking even more VPNs," she told me. "Initial research from local digital rights groups has shown that VPN access varies from one platform to another, and both paid and free services have been affected."

All this translates into an information blackout across the country. For instance, a 60-year-old woman told Radio Free Asia that news is now delayed by at least "four or five days."

Wai Phyo Myint said that, according to local groups, the ramifications of the VPN ban have been wide and deep. Yet, the limited internet access makes it difficult to determine the true scale of the ban’s impact on people's well-being.

"What we do know is banning VPNs further isolates the people in Myanmar from accessing information that could be life-saving during a crisis or surge of violence; it stops people from connecting with loved ones and their community in a safe and secure way, and it stops free reporting of the press on potential human rights abuses," she added.

Many internet users in #Myanmar are encountering difficulties in accessing VPN services and even entering these websites. A new level of techno authoritarianism in the country is emerging as the junta intensifies its state surveillance.To access VPN websites, it is necessary to…June 1, 2024

According to local sources, Chinese tech experts are allegedly working with army generals, from the Transport and Communications Ministry, and a Myanmar technology company (Mascots Technologies & Telecommunication) on VPN censorship tactics. Rumors are circling that these tactics are mainly targeting Western VPN providers, too.

This external support may explain the newly boosted censorship capabilities of Myanmar authorities. David Peterson, General Manager of Proton VPN, confirmed that the Burmese military government is quickly becoming more sophisticated in its censorship capabilities. "Starting out with blocking the use of VPNs at an ISP level, Myanmar is now blocking VPNs at a nationwide level, a rapid step-up in the censorship 'playbook' we have seen time and again in countries like Russia, Iran, and China," he told me.

At the same time, the military junta just released MySPACE, its very own social networking platform, which, an IT expert told Radio Free Asia, authorities plan to use to collect people's information. Access Now believes the two moves might be correlated.

"The military’s MySPACE app was launched at the same time the ban was imposed, I don’t believe this is a coincidence. And it’s not the first time the military has tried to replace platforms like Facebook and YouTube with its own versions, through which they can control communication data including peopleʼs personal information and online content," Wai Phyo Myint told me.

However, she doesn't expect these tactics to be successful. People are aware of the security risks of using these local platforms, with the public consistently boycotting military-developed products in the last three years.

Fighting back against restrictions

While the situation is certainly dire for people in Myanmar and their digital rights, there might still be workarounds to keep access to the open web.

For instance, Peterson said Proton VPN is fully operational in Myanmar at the time of writing. "Proton has invested significantly in anti-censorship technologies, and we are working tirelessly to ensure that citizens in Myanmar continue to be able to access the free and unfiltered internet," he added.

The provider uses different technical methods and tactics to fight back against government-imposed restrictions. This includes its very own Stealth protocol to disguise VPN traffic into something that looks like regular web traffic. Peterson assures the team is working hard to maintain the connectivity on both paid and free plans. Free VPNs are, in fact, reportedly more vulnerable to restrictions than premium services.

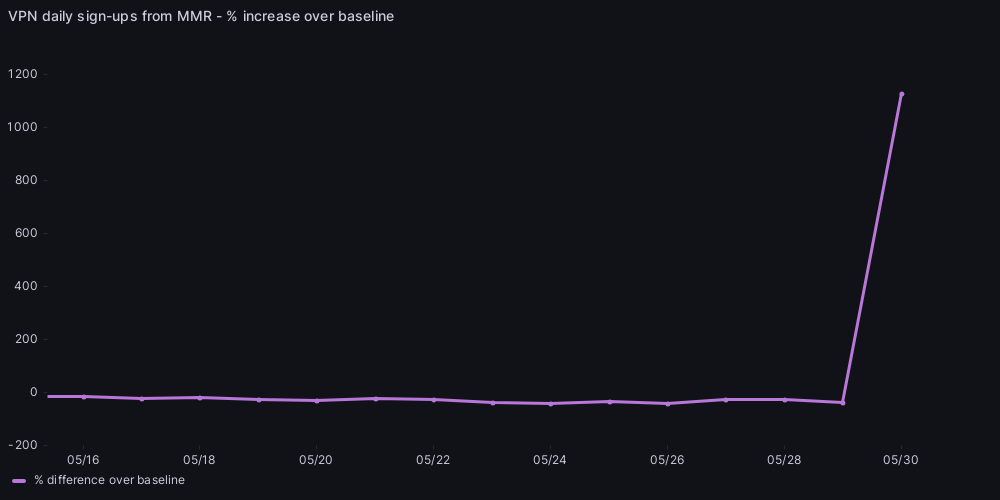

As the graph below shows, Proton VPN sign-ups have increased in recent weeks, peaking at 1200% above baseline on May 30th. While a high level of sign-ups continue today, Peterson explains that the numbers might be even higher as "we have signals indicating that citizens in Myanmar are signing up for VPNs using proxies and other VPNs."

Wai Phyo Myint from Access Now also suggests citizens exchange information on what VPNs still work regularly. She also recommends contacting VPN providers directly or through other organizations to see what options are available.

The Tor browser is also getting more users in Myanmar, an indication that the circumvention tool might be still working in the region. Again, the provider invites users to reach out in case it fails to connect.

"Access Now calls on the international community to dedicate resources towards ensuring people in Myanmar have access to alternate technologies that help them connect to the internet and exercise their right to free speech, assembly, and access information," said Wai Phyo Myint. "We also demand telcos and tech providers to stop doing the junta’s bidding and undermining people’s rights by restricting people’s access and imposing shutdowns and bans."

Chiara is a multimedia journalist committed to covering stories to help promote the rights and denounce the abuses of the digital side of life – wherever cybersecurity, markets, and politics tangle up. She believes an open, uncensored, and private internet is a basic human need and wants to use her knowledge of VPNs to help readers take back control. She writes news, interviews, and analysis on data privacy, online censorship, digital rights, tech policies, and security software, with a special focus on VPNs, for TechRadar and TechRadar Pro. Got a story, tip-off, or something tech-interesting to say? Reach out to chiara.castro@futurenet.com