TechRadar Verdict

The Netgear Orbi 5G WiFi 6 Mesh System delivers enough connectivity for a mansion and 40 people in it. 5G functionality assumes you have service for that technology, and a 24/7 internet service is critical.

Pros

- +

Great specification

- +

5G connection and fail-over

- +

Simple to deploy

Cons

- -

Expensive

- -

Limited Ethernet ports

- -

Not neighbour friendly

Why you can trust TechRadar

Wireless networking equipment has evolved significantly in the past ten years, and it is used more now than it ever has been before.

And, with that use comes both a reliance on it working effectively throughout our homes, possibly in ways that, due to the nature of the technology, are unrealistic.

Originally designed to solve the challenges of WiFi inside office buildings, Mesh has become distributed into more mainstream products, like the new Netgear Orbi hardware covered in this review.

What can spending a substantial chunk of change do for your home WiFi performance?

- These are the best Wi-Fi extenders

- Consider also the popular Google Wifi

Price

The NBK752, or Netgear Orbi 5G WiFi 6 Mesh System to give its full title, has an eye-watering MSRP of £1,099 in the UK and $1099.99 in the US.

That cost is for the 2-pack option, where you get a single NBR750 router and a single RBS750 satellite module. A three-pack with two satellites (NBK753) is available, and also individual RBS750 satellites, increasing the space covered and expanding the system. The triple pack is $1299.98, and any additional RBS750 satellites are $199.99. That price gives you little incentive to buy the satellites bundled in the triple pack, since the purchase price is identical to adding them later.

If this all seems expensive, you probably don’t own the mansion this is designed to provide the coverage for.

Design and features

The Orbi line has from the outset projected this curved persona that makes the components look like vases rather than electronics. Sadly, you can’t put flowers in these, and for the best performance, they need to be in full view.

Our recent review of the Orbi Mini gave us hope that these devices were getting smaller, a promise that was dashed by the NBK752 as it’s the NBR750 router part is the biggest Orbi component we’ve encountered so far.

Weighing a hefty 1247g and measuring 246 x 196 x 86 mm, we’d be concerned if this was mounted on a wall and fell on us. However, unlike the business-orientated Orbi lines, this product has no wall mountings in the box, although you can buy these at additional cost.

The RBS750 satellite is slightly slimmer than the router, measuring 231 x 183 x 71mm and a svelte 861g.

In the box, you get the two components, power supplies for each and a single LAN cable, along with some cursory documentation.

We noted that the PSU for the router is a different design than the one for the satellite, and the router PSU outputs 42W versus 30W on the smaller PSU.

That these are so close in spec and even have the same barrel connector, and yet completely different tooling was made to make each strongly hints at a missed commonality for the Netgear engineers designing these.

The rear of the NBR750 router has three Ethernet ports, one allocated to a WAN broadband connection, two SMA LTE antenna connectors and a Nano-SIM slot for a mobile SIM card.

Amazingly, no SMA LTE antenna are provided at all.

Netgear tells us that the unit will work without them, and only those with connection issues need to invest further. These antennas aren’t expensive, but they’re not an accessory that Netgear sells.

The limited number of Ethernet LAN ports is a concern. With only two on the NBR750 router and only one spare if you want to use a wired backchannel to the satellite, owners might have to buy an extra switch to breakout the wired network to more than one device.

That’s not great, but with only two LAN ports on the RBS750 Satellite, one that might be used to wire it back to the NBR750 and the other needed to chain another RBS750 potentially, you might end up with none free.

Most routers come with four LAN ports, and we’ve even seen designs with eight or 2.5GbE for greater backbone bandwidth, but Netgear has chosen to go in the opposite direction here.

In use

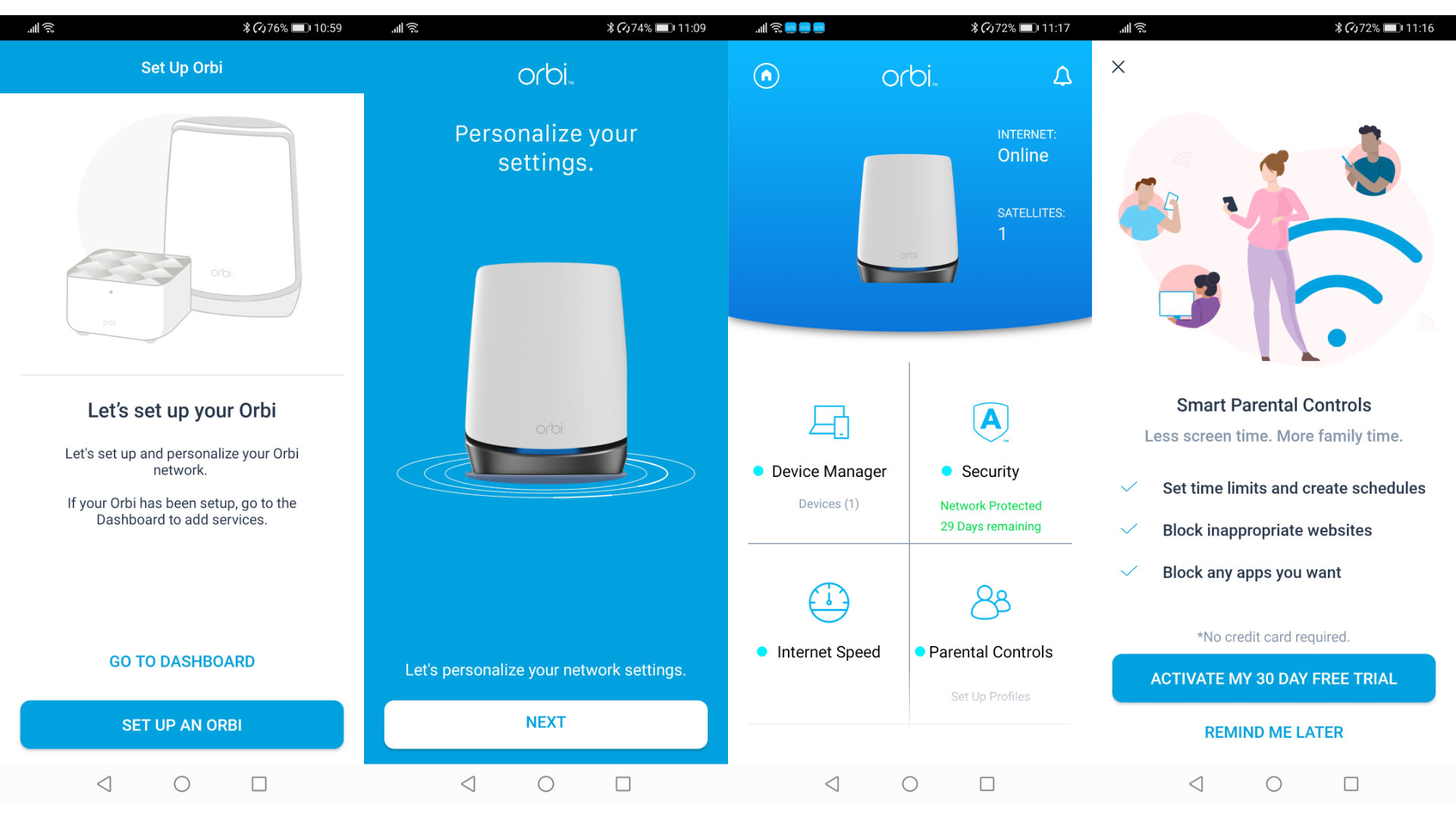

Netgear switched a while ago to use a mobile application to configure their wireless products, available for both Apple and Android phones.

While this does guide a new owner through the setup process effectively, it is also a means to try and sell you Netgear subscription services.

Of these, the subscription being pushed the hardest is a security solution, Netgear Armor, that, after a free trial period, costs $99.99 a year. Alongside that, Netgear has a premium parental control solution for those that like to throw money at their parental responsibilities for another $69.99 (£49.95) per annum.

It always amuses us that a hardware maker like Netgear gets its customers to install an application that then does a ‘security check’ that advises, entirely coincidentally, that you spend more with that company. Who would have guessed?

The Orbi application is an effective tool for getting the hardware operational, but we could have done without the blatant marketing opportunities at every turn.

Performance

We’ve talked about the reality stretching nature of wireless specs in many of our reviews, but if you didn’t catch those previously here, we go once again.

The router and satellite are rated for AX4200 MU-MIMO, inferring that it is capable of 4.2Gbps of wireless speed. Except no one client can get that performance, and even if it was possible to bond the tri-band (2.4GHz and two 5GHz channels) solution used here into a single data stream using a device that could aggregate them, the router only has 1Gbit LAN ports.

A good proportion of the total bandwidth can only be used if WiFi devices are communicating across the router, and not to the Internet or LAN connected devices.

If the connection is via the satellite and it is backhauling over WiFi to the router, the total potential bandwidth is reduced by that router to satellite communications.

Most connected devices will be using the internet or a local NAS connected to a wired network, and those will be the bottlenecks that define what speed client devices will experience.

If you have 100Mbit broadband or 150Mbit 5G, then that’s the best internet performance that one client can experience, even if they can talk to the router or satellite at 1200Mbps.

What AX4200 more accurately represents is the number of simultaneous users that can get higher speeds because of multiple channels, but again, the usefulness of this could easily be undermined by poor broadband or 5G performance downstream.

The final issues that need to be discussed are signal propagation and what 4,000 square feet of coverage can mean in practical terms.

By implication, 4,000 square feet could be an area of 63 ft by 63ft, or 100ft by 40ft, or variations that add up to that area depending on how you space out the router and satellites. For those living in a business or home that is smaller, say only 100ft wide, the WiFi signal will extend out at least 25ft, and possible further, onto adjacent properties. That will occupy channels that they might want to utilise but can’t because of the reach of this system.

If both properties alongside decide to deploy similar hardware, performance is impacted more widely, and everyone that bought this equipment to get better connections is effectively back to square one.

In short, the performance of this equipment is excellent when used in isolation and with client hardware that can exploit the multi-frequency capabilities of WiFi 6, but for exactly the same reasons, your neighbours might find it much less helpful.

Final verdict

We're not sure what the percentage of homes in Europe are close to 4,000 sq ft, with the average UK home being a modest 729 sq. ft. And, even in the USA, the average home is still only 2,500 sq. ft, making this solution overkill for average homeowners in most regions.

For those curious, the common definition of a mansion is 5,000 sq. ft or more, so this hardware is better fitted to those that own one of those.

Using this gear in a smaller house with close neighbours is probably inconsiderate since the signals from it will propagate and reduce the overall performance of WiFi in their homes.

The other issue with this hardware is the concept, promoted by the mobile phone industry, that 5G is equivalent to broadband in performance terms.

The best realistic 5G performance you are likely to see would be around 225 Mbps, even if you are located right next to the mast. That’s well below the 1Gbit speeds that many fibre broadband providers now offer, and only a fraction of the bandwidth in the WiFi available through this equipment.

It can connect to 4G services if 5G aren't available, but that performance is predictably less.

As a fail-over solution, it might make sense, unless whatever stops your broadband working also impacts the backhaul from the 5G mast local to you, like a power cut.

For business users, this type of disaster recovery model has business justification, but for home users annoyed that they can’t watch Netflix 24/7 it seems excessive not only in hardware outlay but paying for a parallel 5G broadband account for those limited times when you might need it.

The hardware price also seems excessive, since the version of this equipment without the 5G capability is less than half the cost at £499.98 ($449.99). Adding this one feature bumps the price up by the cost of a Google Pixel 6 (128GB), and it has no screen, camera, or way to play Angry Birds.

In short, the equipment is predictably excellent at what it does. But we’re unsure about the economics given the excessive cost of the hardware and high overheads for having 5G internet access. Unless you can get a special bundle deal from your Internet provider and have a good 5G service near your mansion, this might not be for you.

- Also take a look at the best Mesh Routers 2021 for the home

You might also want to check out the Asus ZenWiFi AX (XT8) review

Mark is an expert on 3D printers, drones and phones. He also covers storage, including SSDs, NAS drives and portable hard drives. He started writing in 1986 and has contributed to MicroMart, PC Format, 3D World, among others.