I wasn’t a Bob Dylan fan until I watched the Oscar-nominated A Complete Unknown in a 29-channel, 14,500-watt McIntosh and Sonus faber home theater

Dylan goes electric

A Complete Unknown is an Academy Award-nominated biopic that details Bob Dylan’s meteoric rise as an artist in the early 1960s. To be honest, until I saw the film at a private screening in the McIntosh House of Sound’s jaw-dropping statement theater, he was never among my favorite musicians. Surprisingly – or maybe not so surprising – I left the House of Sound theater that night a huge Dylan fan.

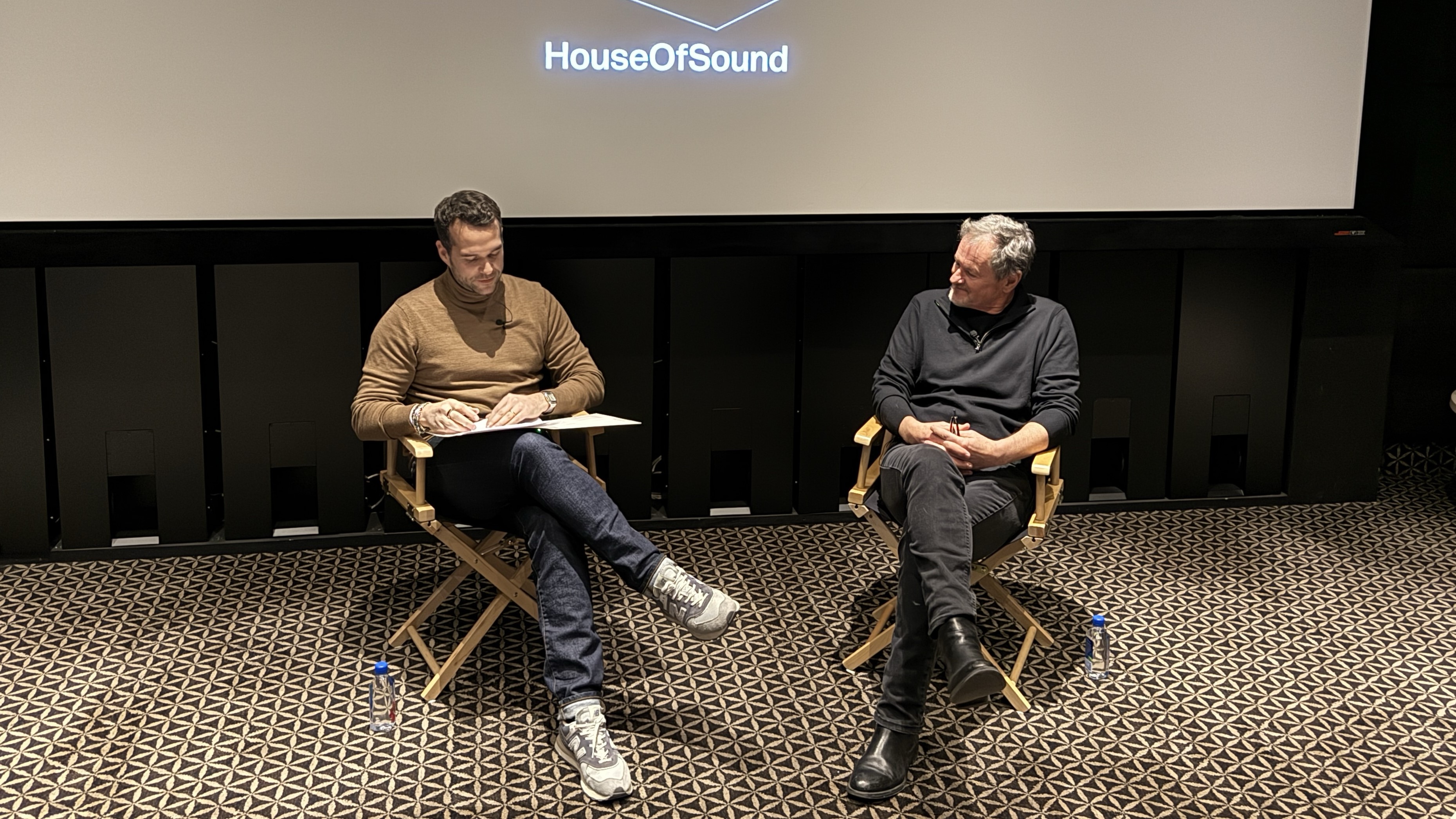

McIntosh had granted me a private pre-movie interview with five-time Oscar-nominated production sound mixer Tod Maitland, who was responsible for recording all of A Complete Unknown’s soundtrack, including dialogue, singing, instruments, and environmental sounds. Maitland, who is highly accomplished in his field, has worked on over 100 movies, including I Am Legend, The Greatest Showman, JFK, Joker, Seabiscuit, Tootsie, and West Side Story.

I had previously visited the 11,000-square-foot, luxuriously appointed House of Sound to experience the movie Top Gun: Maverick. With its massive banks of McIntosh amps and Sonus faber speakers, the theater is a 29-channel, 16-subwoofer audiophile oasis. A McIntosh home theater processor feeds nine monoblock and ten stereo amplifiers that output a total of 14,500 watts. There are 21 Sonus faber Arena speakers spread throughout, ten of which are ceiling-mounted. Sonus also makes the theater’s 16 Arena S15 subwoofers, with four used for LFE (low frequency effects) and twelve timed to work with the Arena speakers.

For video, the theater features a Sony 4K projector, a 204-inch Screen Research screen, and a Kaleidescape movie player.

Recording A Complete Unknown

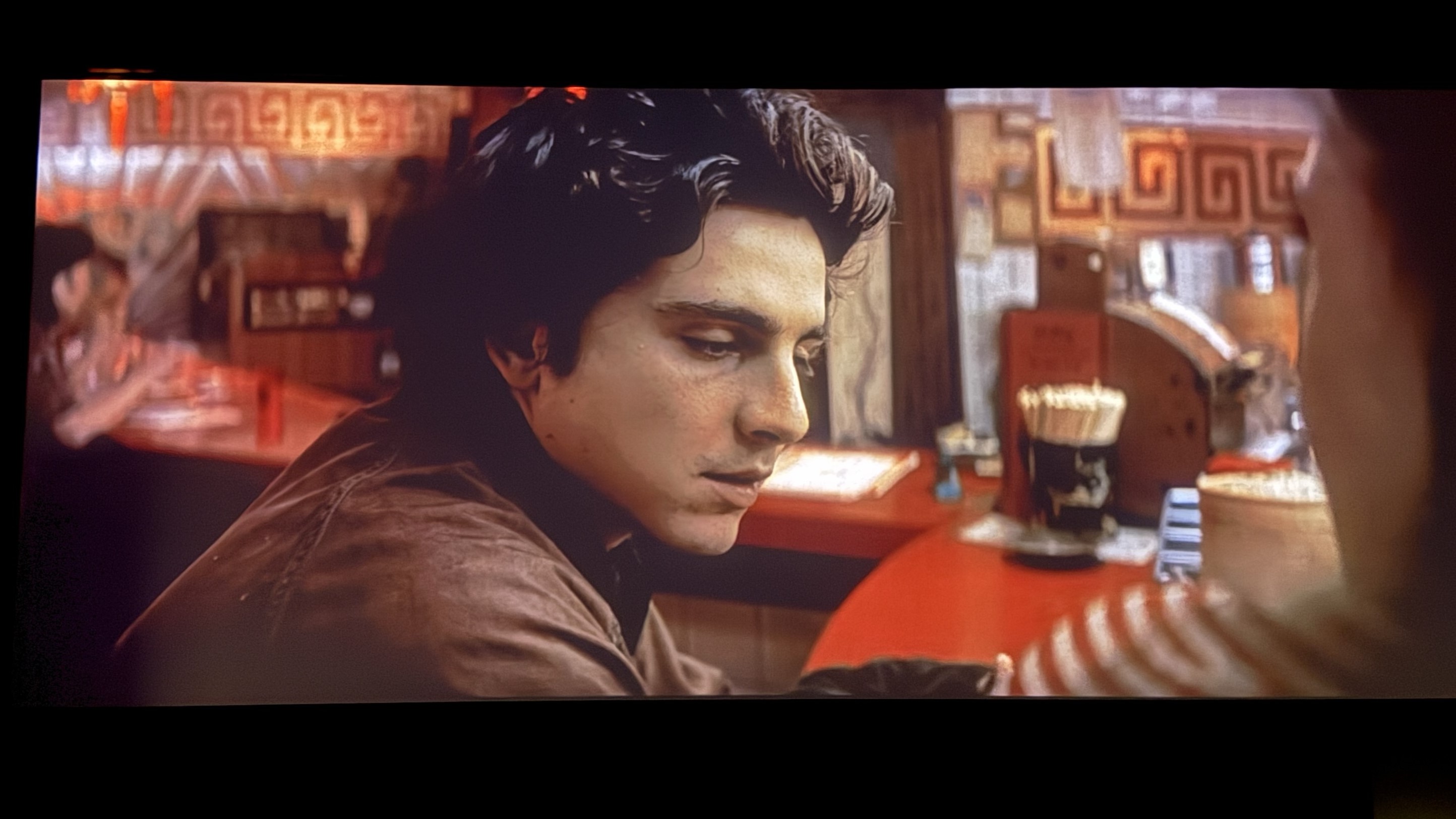

A Complete Unknown was released in December 2024 and stars Timothée Chalamet as Dylan. The movie garnered a total of eight Oscar nominations for best picture, actor, director, supporting actor and actress, adapted screenplay, costume design, and yes, sound.

With its beginning set in the early 1960s, the movie details Dylan’s path to superstardom, including the transition of his music away from its acoustic folk roots to electric rock and roll, which at the time was considered by many to be subversive. The film also explores Dylan’s often strained romantic relationships, including with Joan Baez, and generally reveals him to be a bad-ass.

My first question for Tod Maitland was what, if anything, did he do to get Chalamet to sound like Dylan, to which he replied, “Nothing.” According to Maitland, Chalamet “did it all by himself” and without rehearsal.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Next, I asked Maitland what he did to give the movie’s sound such a 1960s feel. He explained that for the film’s numerous concert scenes, he located and used 42 different vintage microphones, each one appropriate for a specific period in time. According to Maitland, the earliest period mics that were used sounded very “midrangy” but grew sonically more full as the years progressed.

When I asked Maitland what his biggest challenge was in working on the film, he replied that of the roughly 40 songs Chalamet performed, in about a dozen of them, the scene dictated that he not be in front of a microphone. Chalamet also held his guitar high up on his body, just as Bob Dylan did, and this meant the spot where Maitland would normally locate a lavalier microphone was now unavailable. To get around this problem, Maitland ended up placing a tiny lavalier microphone in Chalamet’s bushy hair, which required some negotiations with A Complete Unknown’s hair technicians.

Following my interview, I joined other members of the press in the theater to attend a discussion between Maitland and David Mascioni, the McIntosh Group’s Director of Brand Marketing. To keep things relatively brief here, the discussion focused on the complex way a music-based movie’s audio gets captured.

According to Maitland, the process typically involves recording all of the instrumentals first and then having professional singers add vocals. The actors are then trained to sing those vocals and perform on instruments based on the musicians’ work. Eventually, it's back to the studio to record the cast singing the tracks, where the sound production manager can feed the prerecorded vocals and instrumentals to an actor’s earpiece. Subsequently, in post-production, the production engineer can use either the prerecorded or “live” recordings, jumping between them as needed.

On A Complete Unknown, Chalamet decided just ten minutes before the film’s first big scene to go live with everything. They discarded all of the prior pre-recorded work and ended up going live throughout production. According to Maitland, Chalamet’s talent and commitment (he spent five and a half years preparing for the film) were the reason they were able to take this highly unusual path. Maitland assumed he would be replacing “a whole lot of” the live guitar sounds and vocals, but he mostly replaced only a small part of Chalamet’s live harmonica work. Even when Chalamet was off camera and other actors were being filmed, Maitland stated, Chalamet was still playing “to keep the energy going on the set.”

Screening time

When it came time for the movie, I could not believe the theater’s sound quality, even with my prior eye-opening experience there watching Top Gun: Maverick. Chalamet’s performance and musical chops in A Complete Unknown were spellbinding and, in a testament to the theater’s McIntosh and Sonus faber gear, the timbre of his voice was spot on. This made it easy to suspend disbelief and accept that he was, in fact, Bob Dylan.

One constant in the movie is that Dylan gets around mostly by motorcycle. In the theater, the sounds of these bikes, which grow increasingly expensive as Dylan becomes more successful, were mesmerizing both in their volume and level of sonic detail.

During the many concerts reenacted in the movie in venues both large and small, I was able to locate the expansive horizontal and vertical placement of clapping and other crowd noises. The sound of Dylan's, um, Chalamet’s, guitar notes were warm and vibrant. Indeed, virtually all of the sonic images were reproduced at an impressively large scale.

The film's environmental sounds were also exceptional. Whether it was someone talking across the street from where Dylan was standing, a car horn honking, or fans screaming as they chased him, each small detail was audible.

During the concert scenes, I repeatedly had to resist the urge to clap and several times lifted my hands to do so. That’s something I have never done before when watching a movie!

Watching A Complete Unknown at McIntosh’s House of Sound opened my eyes to Bob Dylan’s unique and great talent, which is something I knew of but never before paid sufficient attention to. The experience also reminded me that a movie with great sound can be a moving experience that stays with you for a long time. That’s a lesson that never gets old, even for this lifelong audiophile and film lover.

You might also like...

Howard Kneller is an equipment reviewer, columnist, photographer, and videographer. He is a co-founder of The Listening Chair with Howard Kneller, a multi-platform audiophile ecosystem. His popular YouTube channel features not only reviews and factory tours but audio show coverage from around the world. Over the past 15 years, Howard has contributed to AV publications such as Copper, The SoundStage! Network, and Sound & Vision.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.