EVs explained: everything you need to know about electric vehicles

It's time to ditch fossil fuels

From the day it was announced, back in March 2016, the Tesla Model 3 has been billed as the car to take electric vehicles mainstream.

Starting at $35,000, it has a claimed 220 miles of range, is fitted with all of the hardware necessary to drive fully autonomously (Tesla says), and might one day be spoken about by historians in the same breath as the Ford Model T and Citroen 2CV.

At least, that was the case two years ago. Now, as Model 3 production finally speeds up and there’s a chance it might be available in the UK and Europe by the very end of the year, Tesla finds it no longer has the EV market to itself.

General Motors, Ford, Jaguar Land Rover and the Volkswagen Group are all poised to launch electric vehicles of their own, and they will do so with a century of experience behind them.

This gives us the perfect opportunity to take stock and evaluate the current situation with electric cars.

How do EVs work?

Fundamentally, electric cars work in broadly the same way as ones powered by petrol, diesel or even hydrogen. There is a fuel source, a drive unit, and a gearbox to provide motion forwards and backwards. Above this there are passenger and luggage compartments.

Electric vehicles (EVs) are still cars, and anyone who has driven an automatic vehicle will feel immediately at home behind the wheel of one.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

There is a distinct lack of engine noise, of course, and the initial acceleration of EVs is often greater than that of an similarly sized internal combustion car. Or, in the case of the Tesla Model S P100D, EVs can literally be the quickest accelerating cars on sale today.

Due to their huge weight, the batteries of EVs are fitted to the floor. This not only offers a large and mostly flat space for the cells to sit, but also helps to lower the car’s centre of gravity.

Although they weigh comfortably over two tonnes, the Tesla Model S and Model X offer decent handling because of the heavy battery being low down.

They, like other EVs, also benefit from extra cabin space thanks to there being no transmission tunnel between the seats.

Are EVs different to drive?

The biggest different between internal combustion engine (ICE) and EV cars during everyday driving is the latter’s regenerative braking system, which captures kinetic energy (caused by the forward motion of the car) and feeds it into the battery whenever you lift off the accelerator.

EVs still have a brake pedal, but it can be used less often due to extra retardation caused by the regen system.

Whenever people ask us about electric cars, or when we've with someone when they drive an EV for the first time, we explain how regenerative braking is the biggest difference during everyday driving.

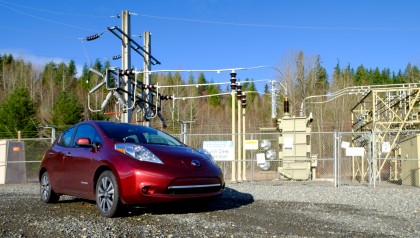

Nissan currently advertises the new electric Leaf by talking about its ‘one-pedal’ operation, where the accelerator is used to speed up and slow down.

This is true, in a way, but the Leaf - as with all cars - still has a brake pedal. It just doesn’t need to be used very often, because electric cars slow down far more abruptly than ICE cars do when you lift off the accelerator.

The best way to think about it is this: lifting off the accelerator a little causes the car to slow gradually, while lifting further or fully off the pedal causes it to slow more sharply, and the brake lights will come on.

Indeed, we’ve often found we can leave a motorway and use only the accelerator pedal to slow down to walking pace by the time we reach the junction.

It only takes a few hours with an EV to drive with one pedal almost all of the time. You only really need the brake pedal in emergencies, when coming to a complete halt, or when driving on a cold morning, before the battery pack and regen system has had time to warm up.

Why electric?

There are many reasons to consider an EV over an ICE car. The obvious one is the lack of localized emissions.

We say localized because, while the car doesn't have an exhaust so can’t contribute to city center smog like a petrol or diesel car, there is still pollution caused during the construction of the car - and in many cases the production of the electricity it runs on, too.

There are many debates to be had here, regarding the environmental impact of producing electricity from a gas or coal-fired power station, and what happens to the lithium battery pack once the car is no longer roadworthy, but that is for another article.

Other benefits of EV ownership include no need to buy engine oil, and less of a need for replacing the disc brakes and pads, because of the regenerative braking I mentioned earlier.

EVs are also quiet, very easy to drive, have automatic gearboxes, and filling the battery with electricity is cheaper than using petrol or diesel to go a similar distance.

If you install a charger at home (as almost all EV owners do) and power this with solar panels, then you can reasonably expect some car journeys to cost you nothing at all.

In some cases you will find parking is reduced or free (as is the case in some London boroughs to promote EV adoption), and there is also no London Congestion Charge or road tax.

In the US, federal tax incentives range from $2,500 to $7,500 for each EV purchased, but this offer will only last until each manufacturer has produced 200,000 electric vehicles.

Tesla will reach that milestone in 2018, and from there the incentive value will gradually decrease. Unless the system changes, many of the 400,000-plus Model 3 reservations holders will receive no discount at all.

It is also worth remembering these are all measures to try and incentive EV ownership, so once EVs become the norm it is likely that these discounts will be adjusted or abolished.

Some public chargers are free, and so too is Tesla’s Supercharger network providing you own a qualifying car, or bought your car with a referral code from a fellow Tesla owner.

What about hybrids?

Hybrids come in several different configurations. First there is the regular hybrid, like older generations of Toyota Prius, which uses both a petrol engine and small electric motor.

The car charges its battery pack using brake regeneration, and can drive itself solely on battery power for short periods of time.

You may well see Prius drivers set off from traffic lights in silent electric mode, but the engine will kick in when they accelerate more firmly. Hybrids like these cannot be plugged in to charge the battery.

Plug-in electric vehicles (PHEV) are becoming increasingly common and act as a half-way house between ICE and full electric.

They can run like a regular hybrid, only topping up the battery when coasting and braking, but can also be plugged in to a public EV charger.

These cars can often cover the daily commute without using their engine, and PHEV technology already appears on a wide range of vehicles, including the VW Golf GTE, Mini Countryman Hybrid and Range Rover P400e.

There’s still an internal combustion engine to maintain, but a nightly charge of the battery means you might not need to use it very often if your commute is short. For example, the Golf GTE and new Range Rover each have an electric range of 31 miles.

Potential lifestyle changes

Living with an EV requires some lifestyle changes. Because public chargers are owned and operated by a number of different companies, you will need to obtain a membership - and often a contactless membership card - for the ones you think you’ll need to use.

It’s a frustrating situation and feels shortsighted - imaging not being able to buy petrol from BP because you only have a membership with Shell - but hopefully this will become simpler as EV adoption spreads.

Next you will need to work out how far your EV can go, and how factors like the temperature affect this. EVs lose charge more quickly in cold weather than in the summer, as the battery takes a longer time to warm up and, just like any lithium battery, is less efficient when the temperature falls.

Manufacturers all provide range claims for their EVs, just like they offer MPG figures with ICE cars - but your mileage will certainly vary. And because EV chargers are less common than petrol stations, you’ll need to put some effort into planning any unfamiliar journeys before setting off.

Also, because chargers are sometimes already in use, or broken, it’s worth having a contingency plan to keep the range anxiety at bay.

Maps of public EV chargers are widely available, and the satellite navigation of some EVs - like the BMW i3 - can guide you to the nearest charger.

Teslas all take into account the company’s Supercharger network whenever you use the sat-nav to get somewhere, and take charge time into account when working out your estimated time of arrival.

For now, owning an EV is only really possible if you have off-street parking at home and space to install a charger. This means those who live in town and city centers - and residents in apartment blocks - will likely be out of luck, unless you are happy to always use public chargers, or perhaps your office has one you can use.

In short, owning an EV requires more journey planning, and those journeys will take longer than with an ICE car when charging en route is required. But these drawbacks are slowly being eradicated, and will continue to fade as EV adoption grows.

Once home chargers are more widely installed - and chargers are included in the car park of new apartment blocks - charging your car at night will become as instinctive as plugging in your phone.

Alistair Charlton is based in London and has worked as a freelance technology and automotive journalist for over a decade. A lifelong tech enthusiast, Alistair has written extensively about dash cams and robotic vacuum cleaners for TechRadar, among other products. As well as TechRadar, he also writes for Wired, T3, Forbes, The Independent, Digital Camera World and Grand Designs Magazine, among others.