Get ready for FIVE new missions to Mars

We could soon know a whole lot more about the Red Planet

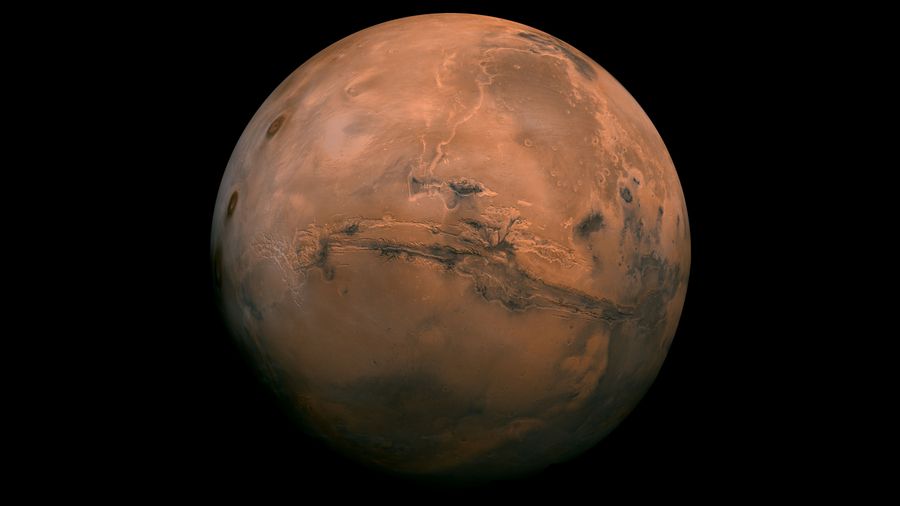

Main image: Mars is getting more attention than ever. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

The fourth planet from the Sun has been in the news quite a bit recently. First NASA announced that its Curiosity rover had found that methane and organic molecules both exist on Mars, and then there was the dust storm that engulfed most of the planet, causing Curiosity to take a very dirty selfie.

We humans are endlessly fascinated by Mars. It's the only other planet in the solar system that we could ever colonize, and it could once have supported ancient life… and yet getting humans to live there successfully will be hugely challenging. The need to know what astronauts can expect when they land on the Red Planet is why space agencies are currently planning no less than five new missions to Mars. Here's what they'll do…

- Do you have a brilliant idea for the next great tech innovation? Enter our Tech Innovation for the Future competition and you could win up to £10,000!

NASA InSight

Launch: May 5, 2018 Touchdown: November 26, 2018 Official mission page

Already halfway through its 301 million mile (485 million km) journey to Mars, NASA's newest lander is due to arrive in November. However, unlike its famous rovers Curiosity and Opportunity – now six and 14 years old, respectively, and still doing science – InSight won't move at all. Since geologists know very little about Mars’ interior, InSight will take the Red Planet's temperature, measure its tectonic activity, and reveal its deeper structure.

InSight – shorthand for Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport – will be looking for one thing in particular: Marsquakes. Its scientific tools will measure the intensity of waves traveling through the rock, with scientists expecting to see between 12 and 100 Marsquakes during the two-year mission. The seismic data collected will be used to figure out how Mars was formed 4.5 billion years ago, while a heat flow probe thrust into the Martian surface will take the planet's temperature.

Also blasting off with InSight in May 2018 was the MarCO or Mars Cube One mission, comprising two small 'cubesats' that will attempt to report back to NASA on InSight's landing.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Read more: The first-ever mission to study what's under the Martian surface

NASA Mars 2020 rover

Launch: July/August 2020 Touchdown: February 2021 Official mission page

You might think that with a couple of rovers, the stationary InSight, and no less than three orbiters (Odyssey, the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) and MAVEN, NASA would have enough Mars missions on its plate. But no. Based on the design of Curiosity – by now way over its intended operational limit – Mars 2020 is another rover, but this one will collect rocks and soil samples.

Crucially, it will do so in an area likely to have been habitable in the distant past. It will use a robotic arm and a drill to study rocks, and put the really interesting ones in a box for a possible future 'sample return' mission currently being discussed by NASA (see mission 5).

To that end the Mars 2020 rover won't just look for signs of past microbial life, but will also measure weather, wind, radiation and dust, and also demonstrate technologies that will help humans once we get there, such as those for testing oxygen-producing technology and looking for underground water.

So far, so sensible – but Mars 2020 has something special up its sleeve, in the shape of a reconnaissance drone that it will test in the thin Martian atmosphere.

Read more: A helicopter for Mars and four other audacious concepts for space exploration

ISRO Mars Orbiter Mission 2 (MOM 2)

Launch: 2021-2022 Touchdown: 2021-2022 Official mission page

India is going planet-mad. As well as planning a mission to Venus in 2020, the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) will send an orbiter to Mars in 2021. It won’t be India's first launch to Mars; in 2014 it sent the Mars Orbiter Mission (MOM) – also called Mangalyaan – whose Mars Colour Camera (MCC) continues to send stunning photographs back to ISRO's Bengaluru mission control.

The follow-up, MOM 2, doesn't have an official launch date or a payload, but since MOM's instruments largely failed to confirm the existence of methane in the Martian atmosphere, it's highly possible that MOM 2 will see a repeat of the experiment with better tech.

Since all of the other planned Martian missions are concentrating on the planet's surface and subsurface, MOM 2 could have a big role to play in uncovering secrets about the atmosphere. MOM 2 will launch from Satish Dhawan Space Centre (SDSC) in Andhra Pradesh, India.

ESA ExoMars Rover

Launch: 2020 Touchdown: 2021 Official mission page

Think there are tensions between Europe and Moscow? Not in the world of space exploration, where scientists thankfully have a much more universalist (no pun intended) outlook. ExoMars is a joint mission comprising a European Space Agency (ESA)-built six-wheeled surface rover complete with drill and cameras, and a platform built by Russia's Roscosmos space agency.

While InSight will be the first mission to study what's under the Martian surface, ExoMars will be the first mission to actually drill down and get samples. It will use a two-metre drill to create a borehole, study the mineralogy down there, and take some samples to study in its onboard chemical lab. What's it looking for? Organic molecules, of course – evidence of buried life.

Another part of the mission, the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter, arrived at Mars in 2016, but its Schiaparelli lander crashed on descent.

Mars Sample Return (MSR)

Launch: Late 2020s Touchdown: Late 2020s Official mission page

Land a rover near cache of rocks left by the Mars 2020 rover. Use a new rover to collect the cache and bring it back to the landing platform. Strap it to a rocket, launch it, and wait for it to travel back to Earth and drop it into the ocean for NASA to collect. Although its only a proposed mission with no confirmed date, NASA is awfully keen to get its hands on some Martian rock for the first time, so that it can perform detailed chemical and physical analysis well in advance of sending astronauts to the Red Planet.

This is high-profile stuff – bringing back a sample from another planet is what planetary scientists have long dreamed of. However, it's not simple. Not only would the Mars 2020 rover need to collect many surface samples and put them in pen-sized canisters for possible retrieval, another mission would be needed to deliver both a rover and a Mars Ascent Vehicle (MAV) rocket to the surface. After some of the samples had been retrieved, they would have to be blasted from the surface – something never attempted before. And, lastly, a third mission would have to scoop the samples out of orbit and put them in an Earth-re-entry vehicle for splashdown, quarantine and scientific study.

Does that all sound rather tricky? It is – and it's why some think that a mission so logistically complex is exactly the kind of thing NASA and ESA should attempt well ahead of any manned mission to Mars. No wonder, then, that it's now being talked up by the two space agencies.

After all, if we're ever going to send people to Mars, we'll need as much information as we can get about what the Red Planet is really like – and, more importantly, how humans can survive it.

TechRadar's Next Up series is brought to you in association with Honor

Jamie is a freelance tech, travel and space journalist based in the UK. He’s been writing regularly for Techradar since it was launched in 2008 and also writes regularly for Forbes, The Telegraph, the South China Morning Post, Sky & Telescope and the Sky At Night magazine as well as other Future titles T3, Digital Camera World, All About Space and Space.com. He also edits two of his own websites, TravGear.com and WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com that reflect his obsession with travel gear and solar eclipse travel. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners (Springer, 2015),