Meet the AI that busts open classic songs to make new tunes

Mining the songs of the past for the future of music

Whatever kind of music you listen to, the art of remixing is an integral part of popular music today. From its earliest roots in musique concrète and dancehall artists in 60s Jamaica to the latest Cardi B remix, repurposing and rearranging songs to create new material has long been a way for musicians to discover new and exciting sounds.

In the early days of electronic music production, music was remixed by means of physical tape manipulation, a process mastered by pioneering sound engineers like Delia Derbyshire, King Tubby and Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry. And the process largely remained unchanged until the advent of digital music.

Nw, remixing is on the verge of another big transformation – and AI company Audioshake is leading the charge. We spoke to Audioshake co-founder Jessica Powell about how the company is using a sophisticated algorithm to help music makers mine the songs of the past to create new material, and about potential future applications for the tech in soundtracking funny Tik-Tok videos, advertising, and making virtual live music concerts sound great.

From small stems grow mighty tracks

Speaking to TechRadar in between appearances at a conference in Italy, Powell told us how Audioshake’s technology works.

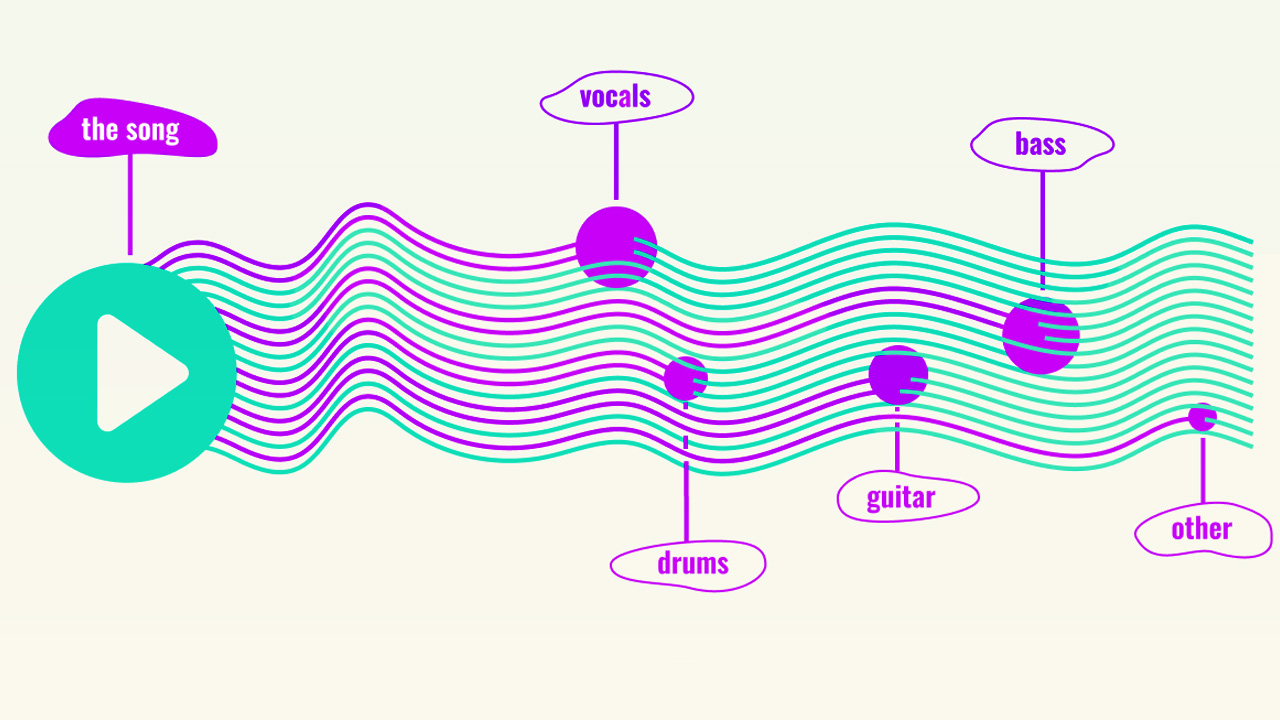

“We use AI to break songs into their parts, which are known by producers as stems – and stems are relevant because there’s already lots you can do with them, like in movies and commercials,” she explained.

Working with these stems allows producers to manipulate individual elements of a song or soundtrack – for instance, lowering the volume of the vocal when a character on screen begins speaking. Stems are also used in everything from creating karaoke tracks, which cut out the lead vocal completely so that you can front your favorite band for three minutes, to the remixing of an Ed Sheeran song to a reggaeton beat.

And, as Powell explains, stems are being used in even more ways today. Spatial audio technologies like Dolby Atmos take individual parts of a track and place them in a 3D sphere – and when you’re listening with the right speakers or a great soundbar, it sounds like the music is coming from you at all angles.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

So, if stems are used so widely in the music industry and beyond, why is Audioshake even needed? Well, record labels don’t always have access to a track’s stems – and before the 1960s, most popular music was made using monophonic and two-track recording techniques. And that means the individual parts of these songs – the vocals, the guitars, the drums – couldn’t be separated.

That’s where Audioshake comes in. Take any song, upload it to the company’s database, and its algorithm analyses the track, and splits it into any number of stems that you specify – all you have to do is select the instruments it should be listening out for.

We tried it for ourselves with David Bowie’s Life on Mars. After selecting the approximate instruments we wanted the algorithm to listen out for (in this case, vocals, guitar, bass, and drums), it took all of 30 seconds for it to analyze the song and break it up into its constituent parts.

From there you can hear each instrument separately: the drums, the droning bass notes, the iconic whining guitar solo, Rick Wakeman’s flamboyant piano playing, or just Bowie’s vocal track. And the speed in which Audioshake is able to do this is breathtaking.

“If you’re a record label or music publisher, you can kind of create an instrumental on the fly,” Powell explains. “You don’t have to go into a DAW (Digital Audio Workstation) like Ableton or Pro Tools to reassemble the song to create the instrumental – it’s just right here on demand.”

So, how does it work? Well, the algorithm has been trained to recognize and isolate the different parts of a song. It’s surprisingly accurate, especially when you consider that the algorithm isn’t technically aware of the difference between, say, a cello and a low-frequency synth. There are areas that do trip it up, though.

Heavy autotune – Powell uses the example of “artists like T-Pain” – will be identified as a sound effect as opposed to a vocal stem. The algorithm can’t yet learn from user feedback, so this is something that needs to be addressed by developers, but the fact that these stems can be separated at all is seriously impressive.

The right to record

Sadly, Audioshake’s technology isn’t currently available to the humble bedroom producer. Right now, the company’s clients are mainly rights holders like record labels or publishers – and while that might be disappointing to anyone who’d love to break apart an Abba classic ahead of the group’s upcoming virtual residency in London, the tech is being utilized in some really interesting ways.

One song management company, Hipgnosis, which sees songs as investment opportunities as much as works of art, owns the rights to an enormous back catalogue of iconic songs by artists ranging from Fleetwood Mac to Shakira.

Take Van Gogh’s Sunflowers. We’re not just going to go and pop out a sunflower if you don’t want us to.

Jessica Powell, co-founder of Audioshake

Using Audioshake, Hipgnosis is creating stems for these old songs and then giving them to its stable of songwriters “to try to reimagine those songs for the future, and introduce them to a new generation”, as Powell puts it, adding “You can imagine some of those beats in the hands of the right person that can do really cool things with them.”

Owning the rights to these songs makes these things possible – and opening up the technology to the public could be a legal quagmire, with people using and disseminating artistic creations that don’t belong to them. It’s not just a legal issue, though; for Audioshake it’s an ethical issue too, and Powell makes it clear that the technology should work for the artists, not against them.

She says the company “really wanted to make sure that we respected the artist’s wishes. If they want to break open their songs and find these new ways to monetize them, we want to be there to help them do that. And if they’re not cool with that, we’re not going to be the ones helping someone to break open their work without permission”.

“Take Van Gogh’s Sunflowers,” she adds. “We’re not just going to go and pop out a sunflower if you don’t want us to.

The sound of the future

Traditional pop remixes are just the start, though. There are lots of potential applications for Audioshake that could be opened up in the future – and TikTok could be one of the more lucrative.

The possibilities created by giving TikTok creators the opportunity to work with stems to mash up tracks in entertaining ways could be an invaluable tool for a social media platform that’s based on short snippets of audio and video.

There’s also the potential to improve the sound quality of livestreamed music. When an artist livestreams one of their concerts on a platform like Instagram, unless they’re able to use a direct feed from the sound desk, the listener is going to hear a whole load of crowd noise and distortion.

“Watch something on Instagram Live and you don’t even stick around – you’d almost prefer to watch the music video because it’s bad audio,” says Powell. Using Audioshake (and with a small delay) you could feasibly turn down the crowd noise, bring the bass down, and bring the vocals up for a clearer audio experience.

Looking even further into the future, there’s the potential to use the technology to produce adaptive music – that is, music that changes depending on your activities.

“This is more futuristic, but imagine you’re walking down the street listening to Drake”, says Powell. “And then you start running and that song transforms – it’s still the Drake song, but it’s now almost like a different genre, and that comes from working with the parts of the song, like increasing the intensity of the drumbeat as you exercise.”

It sounds like adaptive music is a little way off, but we know that audio can already be manipulated based on your environment. Just look at adaptive noise-cancelling headphones like the Sony WH-1000XM4, which can turn the level of noise cancellation up as you enter noisy environments – and other headphones models have similar features that automatically adjust the volume of your music based on your surroundings. The XM4’s Speak-to-Chat feature is another example, with the headphones listening out for the sound of your voice.

The applications for running headphones could go even further than this. With the Apple AirPods 3 rumored to have biometric sensors that will measure everything from your breathing rate to how accurately you can recreate a yoga pose, adaptive music could even be used to bolster your workouts when your headphones detect a drop-off in effort – and stem-mining technologies like Audioshake could make it easier for artists to monetize their music in this way.

While adaptive music is unlikely to reach our ears for a few years yet, the idea of breaking open songs in order to make them more interactive and to personalize them is just as exciting as the next generation of musicians mining the songs of the past to create new sounds. Here’s hoping that one day, humble bedroom musicians will be able to mine these songs too, like plucking flowers from a Van Gogh vase.

- Read our guide to the best music streaming services available now

Olivia was previously TechRadar's Senior Editor - Home Entertainment, covering everything from headphones to TVs. Based in London, she's a popular music graduate who worked in the music industry before finding her calling in journalism. She's previously been interviewed on BBC Radio 5 Live on the subject of multi-room audio, chaired panel discussions on diversity in music festival lineups, and her bylines include T3, Stereoboard, What to Watch, Top Ten Reviews, Creative Bloq, and Croco Magazine. Olivia now has a career in PR.