Nvidia in 2021: year in review

Team Green had an eventful year with its fair share of struggles and triumphs alike

2021 was a busy year for Nvidia, one which came with its fair share of successes and excitement; but it was also a difficult time for the company in many respects.

In this article, we’re going to look at the big victories for Team Green this year – like the RTX 3080 Ti, and the strides forward taken with GeForce Now, to mention a couple – as well as the trickier aspects of 2021, like GPU stock levels and the continued notable absence of low-end Ampere graphics cards.

- These are the best graphics cards around

Desktop dominance maintained

It’ll be no surprise to anyone to learn that Nvidia was the dominant force in the discrete GPU world throughout 2021. Going by figures from analyst firm Jon Peddie Research, Team Green held a market share of around 80% – sometimes a little more, sometimes a little less – throughout the year (with AMD having the remainder).

The status quo, then, was very much maintained in this respect, although Intel still remained easily dominant with laptop GPUs (thanks to integrated graphics on the majority of laptops that don’t have discrete graphics, of course). Team Blue could upset the apple cart next year with its Arc Alchemist GPUs which are expected to seriously challenge Nvidia, particularly at the budget end of the market, but we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

Nvidia kept its big lead in desktop graphics cards this year thanks to the quality and powerful performance delivered by Ampere, both in its existing range of GPUs that came out during 2020, and one new model in particular which turned up in 2021.

In total, Team Green launched three fresh Ampere offerings this year, namely the RTX 3060 which was unveiled as a lower-end option at CES in January, and the pepped-up RTX 3070 Ti and 3080 Ti which followed in May.

That RTX 3060 was admittedly a welcome fresh option at the more affordable(ish) end of the spectrum, but it represented something of a slightly shaky value proposition – particularly when you consider stock shortages and price inflation, something we’ll come back to later in this article. And as we pointed out in our RTX 3060 review, its 3060 Ti sibling (launched at the end of 2020) really made more sense for not a lot more money (and still does: for any extra outlay, you’re getting a good whack of extra performance).

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Similarly, the RTX 3070 Ti didn’t add up very well in terms of value, in fact arguably even more so than the RTX 3060. In our review we declared that it didn’t provide enough extra oomph over the vanilla RTX 3070, and that the RTX 3080 offered a lot more punch for not much more money (in terms of MSRPs, that is).

So, while there was some disappointment with the new desktop Ampere launches, the jewel in the crown proved to be the RTX 3080 Ti. This was basically as capable as the mighty RTX 3090 in gaming, but not as expensive (but still, of course, very pricey). It was the big winner for Nvidia’s desktop GPUs in 2021, for sure, although that said, if you were hunting for a good graphics card, you’d probably have taken any of the top-end products at a (relatively) decent price if you could get them (again, as mentioned, we’ll come back to those availability and stock issues).

Ampere hits gaming laptops

2021 also saw the release of RTX 3000 GPUs for gaming laptops, with the emergence of the RTX 3080, RTX 3070 and RTX 3060 mobile versions (with Max-Q variants) at the start of the year in January, followed by the RTX 3050 Ti and 3050 in May.

Broadly speaking, the first clutch of mobile GPUs were seen as a laudable step up in performance from last-gen Turing laptop graphics cards, so thumbs-up there. The complication with these new offerings was the variety of different power configurations within the same models of GPU, meaning that the same graphics card gave different performance levels based on thermals, cooling and so on of the notebook. Indeed, a well-cooled laptop could conceivably offer better performance than a badly-cooled one where the latter has an RTX 3000 GPU which is a tier higher.

The RTX 3050 followed down the line, and was regarded as a decent stab at an affordable laptop GPU. More so than the 3050 Ti which seemed to not offer all that much more in terms of overall performance – and crucially, to be lagging behind the RTX 3060 mobile by some way (meaning it was better to push the budget a little bit further to get the 3060 if at all feasible).

Overall, Nvidia made solid progress with mobile GPUs to beef up gaming laptops considerably, albeit with some models not being quite so compelling.

DLSS keeps up momentum

DLSS (Deep Learning Super Sampling) is Nvidia’s nifty tech which uses upscaling (and AI) to reduce the demands made on your GPU, essentially boosting frame rates with not much impact on visual quality (broadly speaking).

Team Green pushed forward considerably with DLSS in 2021, bringing it to loads more games, and some big-name titles at that. These included Battlefield 2042, Call of Duty: Warzone, Rainbow Six Siege, Doom Eternal, Red Dead Redemption 2, Back 4 Blood, Outriders, Marvel’s Guardians of the Galaxy, Diablo 2 Resurrected, Horizon Zero Dawn, and more (Baldur’s Gate 3 got DLSS in early access, too).

In total, at the end of 2021, Nvidia counts over 140 games (and apps) which now support DLSS (remember, it has to be baked into the game by the developer in order for it to be supported). Nvidia also made further moves to drive DLSS adoption by implementing a plug-in for Unreal Engine, and the Unity engine, so devs can easily incorporate the tech when working with these game engines.

Furthermore, DLSS support for Vulkan and then DX11 plus DX12 games came to Proton, which is Valve’s compatibility layer that allows Windows games to be played under Linux (and will be the driving force behind the Steam Deck). This represents a potentially sizeable boost in performance for DLSS games that might suffer with some slight headwinds due to running via said compatibility layer.

On top of all that, we saw DLSS speed up the first virtual reality games, and it came to ARM-based laptops too (with ray tracing in tow). So there were a number of firsts throughout the year, as well as a hefty increase in supported games, and continued AI-powered refinement of DLSS itself (which is up to version 2.3 now).

What’s also very noteworthy is that in September, Nvidia revealed a new AI-powered GPU twist in the form of DLAA, which is Deep Learning Anti-Aliasing. It basically does the same thing as DLSS to provide a souped-up form of anti-aliasing (smoothing over jaggies in graphics). DLAA has only thus far been used in testing with the Elder Scrolls Online MMO, but we can expect to hear a lot more about this tech next year if it proves to be an effective way to smooth over visuals and give a more realistic overall look to games with a minimal performance hit.

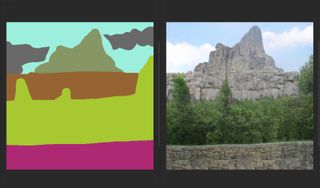

Not-so-blank Canvas

Nvidia unleashed Canvas on the world in June, a free app (in beta) which uses an RTX graphics card in a really clever way for creatives. You simply sketch and doodle rough shapes on the left side of the screen using different material brushes (like ‘stone’ or ‘river’), and on the right, the application fills in AI-generated imagery. The end result is that it’s easy to swiftly create photorealistic images, and if you’ve not seen this in action, it’s one of the coolest things Nvidia achieved during 2021 away from gaming.

Another interesting development for creatives came earlier in the year, in April, when the GeForce Experience software received the ability to quickly and conveniently optimize settings in various creative apps, including Adobe Lightroom and Illustrator. (This is in much the same vein as the optimal settings Nvidia provides for different supported games).

ARM deal stalled

Last year, Nvidia purchased ARM for $40 billion in a huge deal (both literally and figuratively), but in 2021, this big acquisition effectively stalled. Various regulators launched investigations on competition grounds (like the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority watchdog, and the EU), and there have been widespread concerns from tech giant rivals (such as Microsoft, Google and Qualcomm) that an Nvidia buyout could mean that it might become a great deal more difficult to use ARM’s intellectual property.

Most recently in December, in the US the FTC has filed a lawsuit to block the big deal due to it being ‘anticompetitive’, with Director of the Bureau of Competition, Holly Vedova, stating that: “This proposed deal would distort ARM’s incentives in chip markets and allow the combined firm to unfairly undermine Nvidia’s rivals.”

That’s the latest frustration to hit Nvidia with this acquisition, and probably the biggest stumbling block yet – all eyes are on how this case pans out. Team Green has insisted from the very beginning that it will “maintain ARM’s licensing model and customer neutrality” which is “essential to ARM’s success.”

GeForce Now dream stream

Nvidia’s streaming service forged ahead this year, ending 2021 with a total of over 1,100 games available to play, and bringing out a new flagship membership with some considerable benefits.

To put this in perspective, that library of 1,100+ titles is up from 500 games which were present when GeForce Now officially kicked off and left beta. You may recall that a number of major publishers exited stage left post-beta, too, and there are signs that some big names might return to the fold. For example, in October we saw a handful of EA games go live for GeForce Now, and so further products may follow (previously, only Apex Legends was available to stream).

It was a big year for extending coverage in terms of device support, too, as Nvidia introduced GeForce Now to LG smart TVs and Google’s Chrome web browser, along with support for M1 Macs. Further improvements were made to the macOS app in December, in particular to get it to run games in the right aspect ratio for MacBooks, meaning the service can now effectively turn a MacBook into a gaming laptop.

The biggest news, though, was the flagship subscription tier which began to roll out in the US in November (and December in the UK). The RTX 3080 membership delivers resolutions of up to 1440p running at up to 120 frames per second (on PC), and we recently tested it out, finding that it worked really well, running smoothly with a good level of visual detail (when we cranked the graphics settings, with no detriment to the gameplay).

We were seriously impressed on the whole, although it should be noted that you have to pay a fair bit more (double) for the RTX 3080 tier (as you might expect), and that it demands a 70Mbps internet connection for 1440p at 120 fps.

Cloud gaming, then, is starting to look like a genuine alternative to buying a pricey gaming PC, or indeed upgrading your ailing gaming rig with a new graphics card – seeing as buying a GPU has become such an uphill battle. A stupidly steep uphill battle at that; let’s talk about this next…

Stock crisis and GPU price inflation

Graphics cards were scarce throughout 2021 – continuing the theme of last year – and whatever end of the spectrum you were looking at, it was a struggle to find a GPU. And if you did find one, the odds are stacked that the retailer was asking a fair chunk more than the recommended price, or maybe even twice as much (or more).

Bots and scalpers reselling cards on the likes of eBay were clearly part of the problem, but the root cause was the ongoing component shortage which was a major issue last year, and will continue to be a blight on the GPU landscape next year, sadly. Nvidia simply couldn’t make enough graphics cards to supply the considerable demand, and CEO Jensen Huang admitted that these production shortfalls and inventory woes are going to continue through until 2023 (although CFO Colette Kress later hinted that the situation could improve in the second half of 2022).

The themes of scarce stock, scalping and inflated pricing have defined the graphics card market in 2021. Looking at 3D Center, a useful source of regularly updated GPU pricing levels based on major German retailers, asking prices are now double the recommended level.

Yes, as of the latest report for December 2021, you pay twice the MSRP – double what you should – for a current-gen Nvidia graphics card (well, any Ampere model save the 3070 Ti and 3080 Ti, newer cards which the report doesn’t include, but which are impacted by similar problems). The same is true of AMD GPUs, by the way, in terms of doubled asking prices, and of course Team Red is facing all the exact same issues with stock shortages and price inflation.

Note that there was a point where GPU pricing fell mid-year, but that was more a case of a correction from stupidly ridiculous prices in May, when Nvidia pricing reached triple the MSRP (again, all this is going by 3D Center, and just one set of figures, but the overall gist of huge price inflation is clearly visible in all regions, not just Europe).

There’s no two ways about it: 2021 was a terrible year to try to buy a graphics card from Nvidia (or indeed AMD), as if you could find the model you wanted – we’ve got plenty of help resources to that end, in terms of our current stock level guides, incidentally – your wallet would be battered for the privilege. And that was the case for higher-end graphics cards and cheaper boards alike – indeed, let’s talk about the budget market next, which was in even worse shape, in many respects.

Budget GPU gap

Budget graphics cards remained a very sore point in 2021, not just for Nvidia either, but obviously it’s Team Green we’re focused on here. With current-gen Ampere, the lowest-end desktop card was the RTX 3060, and as we’ve already discussed, it’s a shaky value proposition compared to the 3060 Ti – and with a recommended price of $329 / £299, it isn’t a ‘budget’ option (and of course, you can’t get one that cheap anyway). We still remember the days when a few hundred notes got you a next-to-flagship tier GPU…

Anyway, there were RTX 3050 and 3050 Ti laptop GPUs released as outlined above, but no desktop models, so anyone looking for a cheap Ampere graphics card was on a hunt for a non-existent board, basically. (As it stands at the time of writing, the desktop RTX 3050 (maybe even two versions of it) is rumored to be in the pipeline for the near future, in theory turning up in January 2022).

During this year, those wanting to buy a budget GPU from Nvidia have been left scrabbling around at the bottom of the barrel in a manner which would not have been imaginable pre-pandemic. Buyers have been looking at grabbing something like a GTX 1650 Super, a GPU from two years back; and paying through the nose for the privilege, too. Seriously overpaying, in fact (like double or even perhaps pushing towards triple the original launch price).

Sadly, 2021 was the year when, in some scenarios, it made sense, at least for more enterprising buyers, to buy a full PC just to strip out the GPU for their existing rig, and sell that new computer immediately on the used market (with their old GPU inside) to get a good chunk of their outlay back that way.

Pricing for even last-gen Nvidia GPUs being hugely inflated due to sheer demand led to some people looking further back to second-hand cards from older generations still (like GeForce 10 series, or even 900 series models), which represented better value for money as a stopgap solution.

In short, it’s been a terrible year to need a cheap graphics card, or any graphics card at all for that matter.

Turning to Turing

So, it’s no wonder we saw Nvidia trying some decidedly leftfield tactics late in 2021, namely resurrecting an old Turing model: the RTX 2060. Admittedly with double the video RAM and a bolstered core count (it’s loaded with the same amount of CUDA cores as the old RTX 2060 Super, in fact, although it has slower memory than the latter).

The broad idea was to relieve the pressure on RTX 3000 demand, and frustration about there not being nearly enough cards out there, by turning to an older-gen GPU which could theoretically be produced in numbers alongside cutting-edge Ampere boards as it’s an older (12nm) process.

This fudge tactic didn’t pan out, however. Nvidia launched the RTX 2060 12GB version quietly in early December, with cards just coming from third-party manufacturers. The problem being that there was no stock available right out of the gate. At the time of writing, we still haven’t seen the revamped RTX 2060 hit the shelves – by the time you read this, the GPU may have started to trickle out though, as Nvidia has promised availability from late December. So, in short, the GPU rereleased to help mitigate stock shortages suffered from an immediate stock shortage.

To make matters worse, what we’ve glimpsed of initial pricing makes it look like the RTX 2060 12GB is going to end up seriously expensive, and just not worth it anyway. We’ll have to see how pricing settles down, but in a world where the GTX 1650 Super commands a serious premium above its launch price as we’ve seen, we’re not holding out much hope for anything sensible to happen here.

Particularly as there’s another dark cloud here, and that’s the chatter that crypto-miners may fancy this GPU, which could hit availability even harder. This is because the 2060 12GB looks to be at least a serviceable prospect for mining Ethereum (the coin which gained serious traction this year), and doesn’t have the hash rate limiting imposed on RTX 3000 LHR (lite hash rate) models.

LHR was Nvidia’s bid to artificially hamstring Ampere graphics cards for miners this year, in an effort to make sure they got into the hands of gamers instead. But there have already been hacks that partially work around LHR restrictions (and mean that while miners lose some performance, the penalty is no longer as much as Nvidia intended).

Elsewhere in high-end Nvidia GPU land, firmware tweaks made by EVGA in December (and possibly other card makers in the future) have boosted mining performance (even though that wasn’t the intention). Any additional mining demand, of course, has only made things worse for gamers trying to buy an Nvidia GPU.

Finally, it’s worth noting that Nvidia’s efforts to produce cryptomining processors (CMPs) as an alternative to miners buying GeForce cards proved rather ineffectual, and sales of these CMPs slumped badly as 2021 rolled onwards.

Concluding thoughts

Nvidia held fast with its grip on the GPU market this year, continuing to dominate AMD in discrete desktop products – to no one’s surprise, of course – and strengthening its range of Ampere graphics cards principally through the launch of the excellent 3080 Ti. Of course, the RTX 3000 series was strong already, so it didn’t really matter that the other desktop additions (RTX 3070 Ti, 3060) were arguably much less effective.

On the mobile front we witnessed a whole slew of fresh RTX 3000 offerings which represented a very welcome step up for gaming laptops, and Nvidia backed this up by taking considerable strides forward with DLSS, spreading it further (to some big-name games, and various popular game engines) and wider (to Linux gamers via Proton, plus VR gamers). DLAA was revealed, too, and looks like a compelling sibling for DLSS.

Where things fell down was with the woeful stock levels of RTX 3000 graphics cards, which – compounded by scalpers, and miners – sparked huge price inflation. Of course, we can’t blame Nvidia for a global component shortage, and rival AMD was in the same boat here.

What was more frustrating, though, was the disappointing lack of any movement at all in the budget GPU sector. RTX 3050 models came out for laptops, but despite desktop versions being rumored since the very start of the year, they never emerged – which is quite possibly tied in with production capacity being stretched too thin as it was, we can speculate.

The RTX 3050 is expected to be just around the corner now, finally, possibly arriving in January 2022, but we really could’ve used it – and some quantity of the revamped RTX 2060 12GB for the matter – at the tail end of this year, just to give folks more options at the cheaper end of the scale. (Although doubtless RTX 3050 price tags would have been considerably inflated, it’s all relative – and would certainly beat paying through the nose for a GTX 1650 Super, which is what it came down to for some gamers as 2021 drew to a close).

If you couldn’t find a new GPU to bring a fresh lease of life to your gaming PC, mind, there was always another option: play Cyberpunk 2077 with ray tracing (or other super-taxing titles) on your Chromebook, MacBook, or anything – like your smartphone – with GeForce Now. Nvidia’s streaming service really impressed us, particularly the flagship RTX 3080 membership which rolled out this year, representing a whole new level of cloud gaming.

We can’t wait to see how Nvidia pushes forward with this streaming offering – hopefully bringing the likes of EA and other big-name publishers fully back into the fold – next year, coupled with what’s next for DLSS combined with DLAA, and of course next-gen RTX 4000 (‘Lovelace’) cards which are expected to debut later in 2022.

The other fascinating point of focus for the GPU arena early next year will be that purported RTX 3050, and how it will fare against AMD’s rumored RDNA 2 budget cards, and perhaps more importantly, Intel’s new Arc Alchemist products – with Team Blue thought to be preparing a big attack on the budget sector. Exciting times indeed.

- Check out all the best gaming laptops

Darren is a freelancer writing news and features for TechRadar (and occasionally T3) across a broad range of computing topics including CPUs, GPUs, various other hardware, VPNs, antivirus and more. He has written about tech for the best part of three decades, and writes books in his spare time (his debut novel - 'I Know What You Did Last Supper' - was published by Hachette UK in 2013).