Should Netflix come with a warning label?

Binge-watching is a new phenomenon we need to be wary of

‘Binge-watching is the new mindfulness.‘

That was a theory posited at a recent panel debate on the growing trend of hammering through ‘box-set‘ TV series in marathon viewing sessions, and it immediately set off an alarm in my mind.

Mindfulness? Really? Should we class binge-watching as a chance to switch off, meditate and calm our minds… or as another form of addiction that’s being spread across all demographics as access to online streaming platforms grows at a rapid rate?

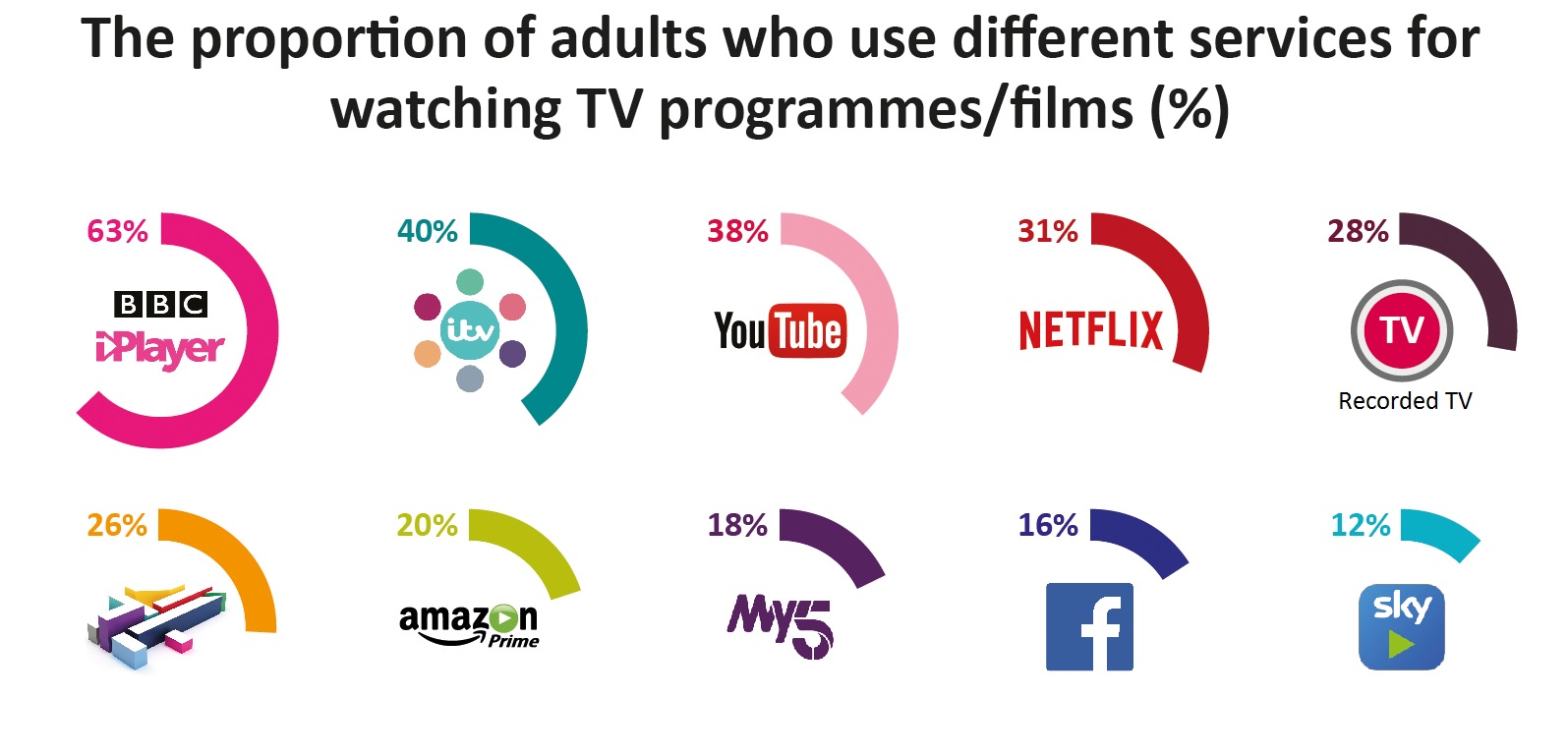

According to a recent report by UK telecoms regulator Ofcom, there are 40 million people in the UK alone using online services to watch multiple episodes in one sitting, so there’s clearly an appetite for this ‘new’ way of consuming content.

The panel that was convened to discuss the topic of binge-watching was certainly well qualified. It featured key players from Samsung, UK mobile network Three and Netflix, all of whom have a decent idea of how the streaming market looks at the moment, at an event to promote the network’s new unlimited media streaming plan.

An interesting question was posed: should Netflix come with a warning before streaming begins, in the same way as news programming warns of flashing images?

The case was made that streaming services are possibly having harmful effects on health, for example by altering the sleeping patterns of people desperate to watch ‘just one more’ episode of their favorite shows… and that making content even more accessible on the mobile could only compound that issue.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

That theory was backed up in the Ofcom report, which said a third of adults using the streaming services were caving into the temptation of watching another episode, and that this was costing them sleep. As a result many were trying to ration their viewing, find something else to do or even canceling their access altogether.

How much is too much?

The question of whether binge-watching is harmful to health isn’t something that can be easily or conclusively answered. It’s incredibly subjective, and depends in part on how you define bingeing.

Some people will stream a series over several weeks, their self-rationing automatic. For others, the craving to devour a series in one sitting is all-consuming, meaning they’ll push the boundaries to watch it as quickly as possible. That can include forgoing sleep – and that’s something that does carry associated health risks.

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine has issued advice on making sure binge-watching doesn’t affect your daily life – although Netflix apparently treats the fact that people will lose out on sleep as a positive, rather than a risk factor.

Sleep is my greatest enemy.April 17, 2017

Chris Whiteley, Director of Partnerships at Netflix and Three CEO Dyson agreed that most users are aware of their limits when it comes to binge-watching, but emphasized that self-regulation was important.

Whiteley went on to say that he didn’t see over-consumption as a huge problem, pointing to the fact that the streaming platform encourages people to “binge responsibly”, that the platform is “giving freedom and putting choice in people’s hands“ and that the brand is trying to use ratings and content warnings to allow people to decide when and how much to watch.

“We’d much rather people made the decision themselves (whether or not to binge),“ he said. “People are pretty smart.“

David Dyson, CEO of Three UK, also pointed out that online streaming services like Netflix aren’t the beginning of bingeing.

“I didn’t see [such] warnings on the front of a book, saying excessive reading could make you blind by 18,” he said. “People will generally know their limits.”

Born to binge?

This is one of the key points in the debate over whether binge-watching offers a positive or negative effect on health – people will always be drawn to what they enjoy.

Video games, after all, can come with a warning about excessive use despite being something you’d imagine people would self-regulate – and yet books don’t.

However, until recently TV had never offered the same all-or-nothing consumption option as books, with weekly scheduling dictating how quickly you’d move through a storyline. It wasn’t until the DVD box set appeared that people started to gorge on content.

Hilda Burke, who's an integrative psychotherapist, couples counsellor and life coach, says the shift in how series are being delivered could be giving rise to a new kind of temptation.

“I think it's simply the 'supply'. If you only have one episode per week shown, like in the old days, your consumption is naturally limited to that one episode per week,“ she says. “With a whole bunch of episodes dropped at once, the only thing between yourself and bulk consumption is your self-control.“

But there’s a key difference between the way books and TV are consumed: reading is something you need to actively engage in, whereas lying back on a sofa and letting pixels fall into your eyes requires no effort at all.

You can even fall asleep and it’ll still rumble on – whereas with a book the only thing that might happen is you’re startled as the heavy tome strikes you in the face.

Even a DVD marathon has an active element within it – when your disc is finished, you need to decide whether to get off the sofa/out of bed and load the next one.

With Netflix not only is that proactive element removed, but the new autoplay feature is an ever-present temptress, cajoling you to move to the next episode without needing to do a thing, aside from tapping a button after a while to ensure you’re still watching.

And it's this that’s raising questions over our shifting viewing habits – that fact that we can be fed endless excitement by literally just sitting there.

A shifting future

It’s hard to say what place services like Amazon Prime Video, Netflix and other online services have in the digital, always-connected world more and more, of us inhabit these days.

But the recent fall in levels of mental well-being in the UK is a worrying trend, and it’s been hypothesized that our connected lives are to blame.

While boredom is generally perceived as a negative thing, it’s also the time when the brain switches off from constantly searching for the next reward, and that’s crucial to mental wellbeing.

Andy Puddicombe, co-founder of online meditation and mindfulness service Headspace, says that the increase in digital stimulation is causing users to seek counterbalance.

“It means that for many, the mind is in a constant state of activity, stimulation and distraction,” he adds. ”We might be able to manage this for short periods of time, but over an extended period the mind is simply unable to keep up, it gets tired and may even burn out. This is why it’s so important to build in some time to rest the mind.”

“Obviously meditation is a great way to do that, and many of the people who try Headspace do so at first as a way to cope with digital overload.”

The Ofcom study mentioned above proves that – in the UK at least – binge-watching is enjoyed far more by the younger generations, with 53% of young teenagers enjoying long sessions of series watching, compared to the 16% of over-65s.

Just what this access to so much content is doing to the human psyche still needs to be studied, but it’s hard to argue with the fact that today’s generation is being exposed to vastly more information than any that’s preceded it, and enjoying instant gratification through content. But why is that happening?

Are smartphones making us dumb?

The fact that our smartphones are the portal to all this content and information is creating some potentially excessive behaviours, with studies showing that social media especially is causing Pavlovian reactions amongst users; the constant scrolling and responding to the buzz or ping of a notification, and the sheer immediacy of connection to others, mean boredom is increasingly hard to achieve.

Some characterize this action as triggering the ‘pleasure chemical’ of the brain (often – mistakenly – referred to as dopamine), and our dependence on smartphones as a constant desire to trigger the sweet hit of that neurochemical.

While that’s been proved to be a myth, dopamine could still be to blame for the current decline in mental health, as its presence in the brain causes a ‘seeking’ effect in the subject. That seeking could be for food, information, movement, comfort, distraction… it’s a key motivator in how we live our life, and its absence has been linked to depression.

And constant access to information is only going to stimulate that seeking mechanism, with so much available and so readily, the tantalizing thought of learning, happiness or laughter always around the corner.

There's the suggestion that we’re all becoming devoid of self-control, the lack of enforced quiet meaning we never let our brains switch off and rest – which is an intangible need but one that you feel would be dangerous to lose.

Alastair Mordey is programme director at The Edge, an addiction rehabilitation center in Thailand. He says that device addiction is something the center encourages young men that seek help to break, asking them to leave their phones at the door when entering the facility.

“We encourage our young men to put down their mobile devices and engage in meditation and sports such as triathlon and kickboxing,“ he says. “Cardio[vascular] exercise encourages the growth of new brain cells, lowering depression and anxiety, and meditation increases the density of grey matter in the brain which increases the ability to concentrate.“

In researching the dopamine myth, we came across a viral video featuring Simon Sinek, one which mistakenly blames dopamine as partly to blame for it being so hard to manage the millennial generation.

While that’s been proven incorrect, the video does make a valid point: newer generations are being imbued with the belief they can achieve as much as they want, that they can be as socially mobile as they can handle, and with so much pleasurable information and entertainment around, it’s a feeling that quickly gets confirmed – but could leave them susceptible to struggling with failure in adult life.

So what does this all have to do with online streaming? Well, in order to deal with this information overload and the stress it can bring, many look to extreme escapism – ironically using the very device that could be causing it in the first place.

Binge-watching becomes an instant form of digital distraction, a chance for the mind to rest while digesting simple and enjoyable stories. Just because Netflix or Spotify is as instantly accessible as scrolling through Twitter, it doesn’t mean it’s the cause of the problem though.

A positive activity

There are undoubtedly positives to binge-watching and this instant access to so much content. Headspace’s website even has blogs on the positive effects of enjoying a series session with a loved one, enjoying shared laughter or engaging emotionally with a character and that providing insight into your own relationship.

In fact, it’s impossible to classify binge-watching as positive or negative - something Headspace’s Puddicombe believes is more to do with the binger than the activity: “We are all different, and what works for one person may well not work for another.

“If it makes us feel overstimulated, is a cause for insomnia, or means that our relationships start to suffer in some way, then that’s not going to be great for our health.

“But if you have the time, the freedom, the inclination, and you enjoy it, then I don’t see any real harm in it at all.”

It’s clear that mindfulness and the ‘always-on’ culture are at opposite forces, even if neither is necessarily detrimental to health. So to classify online streaming as mindful isn’t something the experts agree with..

“Under no circumstances could sitting down watching TV for hours on end while distracted by an engaging and exciting storyline be considered a form of mindfulness. Nice try though!” laughed Puddicombe.

That’s a view echoed by Smita Joshi, a mindfulness and meditation expert.

“Mindfulness requires that you focus in a way that soothes the mind as well as increases awareness. Binge-watching is more akin to escapism and deferral of the ‘what's so’ rather than becoming more ‘present’ to the entirety and lushness of the moment,” she said.

“So binge watching and mindfulness are not comparable and indeed, are quite opposite to each other. That said, binge watching is sometimes good to do, providing it's done in moderation, because it can help to mentally ‘switch off’. However, it should not in any way be confused with mindfulness or meditation.”

And it’s not like spending hours glued to entertainment is a new phenomenon - we’ve all spent hours mindlessly flicking through TV channels looking for something to watch.

Instead of that people are now being given things to watch they actually are looking forward to devouring. Netflix’s Whiteley says the company has seen a three day gap between users finishing one series and starting another, the time in between often filled with standalone shows, including documentaries or shows related to the series just watched.

The data created using online services allows the platforms to serve up ever-more relevant and enjoyable content to users when they want it, and giving platforms to filmmakers that wouldn’t have had access to such an audience.

“We’re giving people the freedom to watch what they like, when they like,” says Whiteley. “We get [content creators’] stories across - Netflix wants to be a global platform for storytellers to come and tell their stories.

“These stories are commissioned from all around the world - why should people wait three, six or 12 months [to watch it]?.

“Why shouldn’t someone be able to tell that around the world instantly? We can translate it into different languages - it might not have fitted into commercial broadcaster’s [preferences], but if you’re interested, we can get that in front of you.”

Kids are still the future

Perhaps the issue is simply just too recent to understand. Access to information has accelerated exponentially for the last 70 years, meaning each generation is faced with ever-greater opportunities for entertainment… which also brings a challenge for parents trying to ensure their children are growing up with healthy limits.

The worry exists that the younger generation doesn’t have to ‘graft’ for their entertainment or information in the way their elders did, and that will bring a reduction in boredom, stillness or the things that some believe offer our brains the chance to switch off or grow in creativity.

But the same accusation has been levelled at many different activities over the years, and used to demonise the activity rather than consider what it’s actually doing to society.

Hilda Burke agrees that the parent is still the key guardian in the development of children’s mental well-being: “I think there's always some sort of perceived threat to the 'youth of today'. Two generations ago the challenge was TV, then computer games, with a lot of doom-mongering around each in turn would be the ‘downfall of kids’.

"Meditation, when practiced regularly, can become a sacred inner sanctuary.

"Its allure is in the fact it refreshes the mind, energises the body and nourishes the spirit and for this reason, it gently and naturally draws the practitioner in to making it a long term habit.

"It becomes not something to do but a place within yourself where you can 'just be', something to counter all the frantic 'doing' in the digital world.

"With this in mind, meditation, once started, tends to ease its way into becoming a part of your day in an effortless way.

"Given this, meditation becomes a digital detox in itself."

- Smita Joshi, mindfulness and meditation expert

“The fact is, there'll always be something that 'threatens' children's well being or might turn them into lazy couch potatoes unfit for work or to just 'graft' more generally. It's nothing new.

“But by parents setting firm boundaries and modelling a more balanced way of consuming TV, children are likely to pick that up.”

The thing is - we are irreversibly plugged into this digital world as a society. We’re not all going to give up our smartphones to see how it makes us feel, we’re not going to stop checking social media no matter what health organisations warn and services are still going to keep offering high-quality entertainment with almost no barriers to consumption.

But that doesn’t mean it will be a bad thing - just a new thing, only our own guilt at taking such pleasure causing us to worry.

“We are so early in the evolution of this technology. I don’t think we have even come close to finding a healthy balance of how to use it yet,” says Puddicombe.

“Like so many things, we often have to see the two extremes before we find the middle. Part of the challenge right now is that we want everything immediately, but we don’t like how it makes us feel. It’s a bit like eating 10 tubs of ice cream, just because it’s in the freezer, but knowing that it’s not going to feel so good after.

“So this dynamic creates a lot of tension in our life. But I think in the future, there will be a better understanding, whereby people enjoy the convenience of instant, whilst aware of the dangers of overconsumption. That’s the best of both worlds.”

The positives are clear too - whether it’s children being able to virtually interact with a concept through a headset rather than reading it in a dusty old book, or being able to watch documentaries from the other side of the globe as easily as switching on the television, we shouldn’t instantly demonise things like binge-watching just because it seems ‘too easy’.

It’s impossible to predict how we’re going to consume media in the future, or the effect all this information is having on each subsequent generation. But as long as we don’t all live in individual cabins tailored to popular Netflix shows… we should be OK.

Gareth has been part of the consumer technology world in a career spanning three decades. He started life as a staff writer on the fledgling TechRadar, and has grew with the site (primarily as phones, tablets and wearables editor) until becoming Global Editor in Chief in 2018. Gareth has written over 4,000 articles for TechRadar, has contributed expert insight to a number of other publications, chaired panels on zeitgeist technologies, presented at the Gadget Show Live as well as representing the brand on TV and radio for multiple channels including Sky, BBC, ITV and Al-Jazeera. Passionate about fitness, he can bore anyone rigid about stress management, sleep tracking, heart rate variance as well as bemoaning something about the latest iPhone, Galaxy or OLED TV.