The A to Z of photography: JPEGs

All you need to know about the standard file format for digital photos

JPEG has become the standard compressed image format for digital photos, with JPEG images able to be displayed by and edited using practically any program on any machine. Pronounced 'jay-peg', the format uses so-called 'lossy' compression to reduce image file sizes to the point where they take up little space on your computer, and can be transferred in seconds.

But this compression comes at a price, which is why enthusiast photographers and professionals often avoid JPEG files when they can, or use them simply for convenience when they need to share shots quickly or send finished photos to clients, colleagues or publishers.

'Lossy' versus 'lossless'

It's the 'lossy' compression process that can cause problems, because it means you're losing some of the image data. Some compression processes are 'lossless', which means no actual image data is lost, it's simply packed into a tighter 'space'. Many cameras shoot 'lossless' raw files that have all the quality of an uncompressed image file but take up less space, while the TIFF image file format offers a couple of different 'lossless' compression formats.

But even compressed raw and TIFF files are way bigger than JPEGs, making them impractical in many situations, while compatibility issues can arise with raw files. 'Lossy' JPEGs remain the quickest and most efficient format for sharing digital photos with the widest range of devices and users.

But even though this 'lossy' JPEG compression does involve the loss of some image data, it's not always noticeable, and you're in control of just how much compression is applied.

JPEG quality

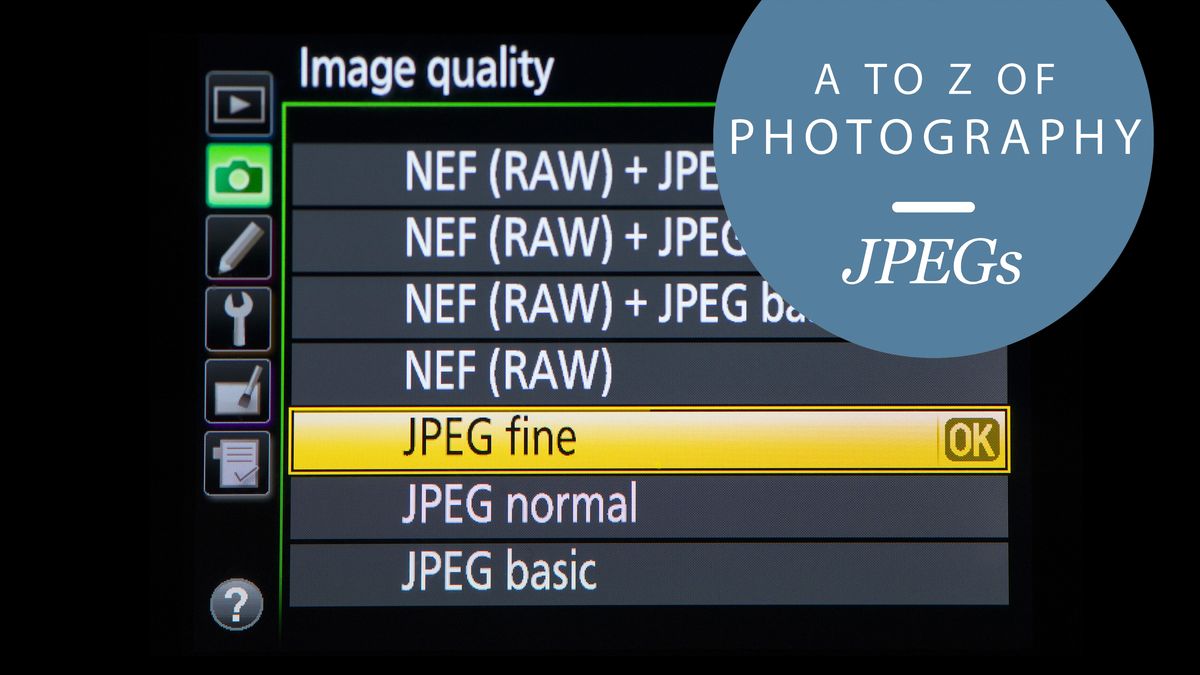

Digital cameras offer different 'quality' settings for JPEG images. Typically these might be Basic, Normal and Fine. Some cameras offer a Super Fine option, while some offer a Low setting instead of Basic. The point is that you can choose just how much compression is applied.

With a Fine-quality JPEG, the chances are you won't be able to see any image degradation at all with the naked eye. With a Normal quality JPEG you may be able to make out some slight softening of fine detail, and perhaps some faint artefacts around object edges, but to the casual observer there won't be any real difference. Low-quality JPEGs will start to show some degradation, but sometimes it's a necessary evil – if you need to send an image over a slow internet connection for example.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You get the same image quality choice when you save a photo as a JPEG in an image-editing program like Photoshop. Here, you might get a choice of Low, Medium, High or Max quality, or a setting out of 10 (or 100). It's the same principle – the higher the setting, the better the quality but the larger the file.

So if JPEGs are so good, what's the problem?

With JPEGs there are two things to be aware of. The first is that the camera has to ditch a good deal of the data actually captured by the sensor when it processes the image. If you've got the exposure right and you don't need to make any big changes to the color rendition or the white balance, or carry out any heavy photo manipulations later, then that's fine – you didn't need that extra data anyway.

But enthusiasts and pros often like to make substantial changes and image manipulations later, and with JPEGs there's not much room for manoeuvre before the quality starts to suffer. That's why many photographers shoot raw files instead, and process them on a computer rather than leaving it to the camera.

The second problem is that while saving an image as JPEG once is unlikely to do any harm, repeatedly editing and saving a JPEG photo will progressively degrade it until the loss in quality becomes objectionable. That's why many serious photographers shoot raw files, and only convert to the JPEG format right at the end of their editing workflow, when they're ready to share finished images with the world.

When to use JPEGs and when not to

To sum up, JPEGs are fine if you're not heavily into image-editing and you just want to share your adventures with your friends, maybe with an Instagram filter thrown in here or there. And they're also fine if you're a purist who believes that photographs should not be manipulated, and likes their camera's rendition just as it is.

Otherwise, if you're really quality-conscious and do lots of manipulation, you should shoot raw files, and save JPEG versions of your edited images only when you need to share them.

Rod is an independent photographer and photography journalist with more than 30 years' experience. He's previously worked as Head of Testing for Future’s photography magazines, including Digital Camera, N-Photo, PhotoPlus, Professional Photography, Photography Week and Practical Photoshop, and as Reviews Editor on Digital Camera World.