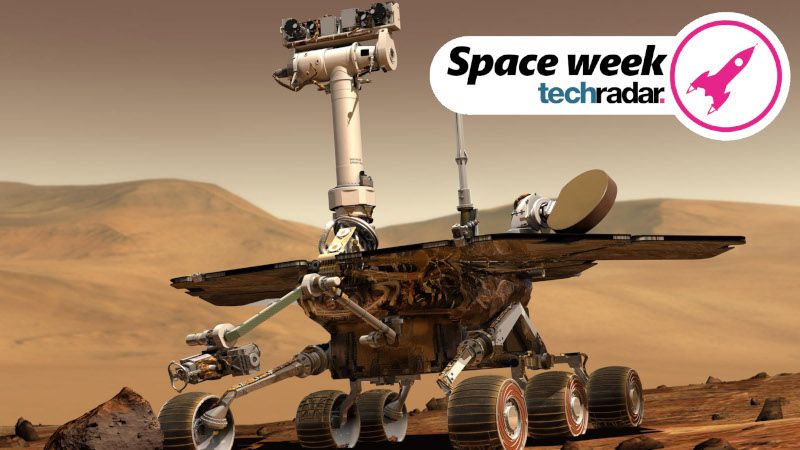

Why do we mourn our space robots?

Our surprising feelings for space-faring machines

The Opportunity rover’s mission was meant to last 90 Martian days – 100 tops – and travel 1,100 yards (1,000 metres). But the rover explored the red planet’s surface for nearly 15 years, exceeding its life expectancy by 60 times and travelling more than 28 miles (45 kilometres).

The little rover that could surpassed all expectations in its endurance and long-term scientific value, which is what made it bittersweet when Opportunity stopped sending signals back to NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in June of 2018. After repeated attempts to revive it, the Opportunity rover’s mission was officially declared over in February 2019.

To say the mission was a success would be an understatement, so why does it feel sad to bid farewell to rovers, diggers and spacecraft when they inevitably go quiet?

Oppy’s mission – and those who came before her

The Opportunity rover, formally known as Mars Exploration Rover B and informally known as Oppy, arrived on Mars on January 25, 2004, with its twin rover Spirit.

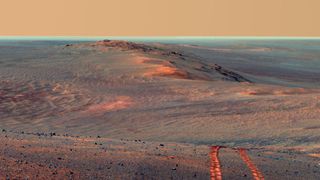

During its time on the red planet, Opportunity explored different regions and found evidence of past liquid water, known as Martian ‘blueberries’. It returned more than 217,000 images, including 15 360-degree color panoramas that are truly breathtaking.

In June 2018, a Mars-wide dust storm blocked out all sunlight to the planet’s surface and meant the solar-powered rover could no longer operate. The last time it phoned home to Earth was on June 10, 2018, when it sent images that showed the sun being slowly blotted out by the dust.

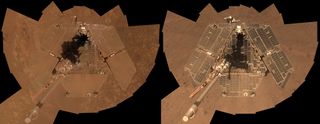

Between then and February 2019, NASA believed that strong winds could wipe the dust away from Oppy’s solar panels, which it had done successfully in 2014. After more than a thousand commands to restore contact, engineers at the Space Flight Operations Facility at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) made their last attempt to revive Opportunity on January 25, 2019. They sent final commands in the hope it’d ‘wake up,’ but it never happened. NASA has said that the rover will remain in a gully that’s been named Perseverance Valley.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

After this announcement, the outpouring on Twitter from the team at NASA, the wider science community and fans of the Opportunity mission was emotional – and it’s not hard to figure out why. Opportunity had kept going against all odds, provided a wealth of scientific data and allowed us all to experience life on the red planet for 14 years.

However, this wasn’t the first time we said goodbye to one of our intrepid spacecraft recently.

On November 15, 2018, the exoplanet-hunting Kepler space telescope received its final set of ‘goodnight’ commands. During its nine-year lifespan, Kepler discovered thousands of planets and gave us an extraordinary look at the galaxy as we’ve never seen before.

Last year, NASA’s Deep Space Network (DSN) also said goodbye to the asteroid-exploring Dawn spacecraft after it visited two of the largest objects in the asteroid belt before running out of fuel after an 11-year mission.

Back in 2017, Cassini plunged into Saturn’s atmosphere after bringing us incredible images of the planet that provided information about the complexity of the planet’s rings and icy moons.

NASA is still in contact with the twin Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft, but now they’ve entered interstellar space it’s taking longer and longer to contact them. Launched in 1977, they explored the outer planets: Jupiter, Saturn and Uranus. They’ve provided such a huge amount of scientific data about our solar system, and have inspired people for decades, it’s bound to feel like a huge loss when they venture too far to receive messages.

Each mission provided NASA with important scientific data about our solar system – and those beyond it. But they also provided us all with a look at exoplanets, asteroids, Saturn, Jupiter and Uranus. These spacecraft weren’t just robotic explorers, they gave us all a deeper connection to outer space.

Saying goodbye to a member of the team

Those who worked directly on these missions bear the brunt of the emotions when they end.

“When you work on a mission – especially on the operational side of it – the spacecraft becomes part of your daily life. You check in on it every day, you 'talk' to it every day. It’s like your robotic colleague,” Dr Tanya Harrison, a planetary scientist and the director of research for Arizona State University’s Space Technology and Science (NewSpace) Initiative said. “We all want people to love our space robots as much as we do.”

Many of the missions typically last for years, which means the team behind them have put a lot of time and energy into them – many have spent most of their careers working on the same one.

When the Opportunity mission officially ended – and in the lead up to the announcement – many of those who played a role in the rover’s journey shared their stories about what the mission meant to them. Some formed strong bonds with their team and met partners during the 15-year mission, others were inspired to pursue careers in science because of Opportunity.

The power of social media

The emotional goodbye to Opportunity spread far and wide. It wasn’t just those at NASA or those in the science community that bid farewell to the rover. The missions made mainstream news and people from all over the world shared their goodbyes.

A big part of this interest – and sense of ownership – comes from the sustained presence space agencies and spacecraft have on social media.

“ESA and JAXA have produced some really fantastic graphics and video for missions like Rosetta and Hayabusa that make you really feel for the spacecraft,” Dr Harrison said. “I actually teared up watching the ESA video of Rosetta losing contact with the Philae lander! Those sorts of things definitely resonate with people and make the science and tech more relatable.”

Providing people beyond the scientific community with updates, photos and future plans is important. It makes them feel part of the mission, gives them a glimpse into space and empowers everyone to learn more about science.

This enthusiasm proves to governments that investment in space exploration is worthwhile. The more interest, energy and backing we have for our future space efforts, the better.

Social media also provides a great opportunity for scientists to connect directly with fans of the missions, giving them access to one-to-one contact that would have been off-limits in the past. Dr Harrison said: “I love that Twitter gives me a way to answer questions from people about Mars rovers all around the world. It’s a total game-changer.”

“Being able to interact with the people working on these missions I think also helps to humanize scientists and engineers, showing that we’re not all old men in lab coats that don’t know how to talk to anyone at a comprehensible level."

Not only is this a fantastic way to connect for those who already have an interest in science and space, but it’s also important for representation. Being able to see who works on the missions and interact with them shows people, especially young people, that these roles exist and they’re not out of anyone’s reach.

These are the droids you're looking for

It’s always sad to see a mission end. But people seem particularly prone to giving rovers personalities and emotions. Many of us think of them as intrepid space explorers and robot geologists – see! But why?

“Rovers I think are even more prone to get attached to because they’re easy to anthropomorphize: They have ‘eyes’ and ‘‘arms’. You can picture them driving around doing science,” Dr Harrison said.

By design, these rovers certainly look more like pets and robots we’ve seen in TV and movies.

“The design definitely plays a role, especially when it comes to us anthropomorphizing rovers and Earthly robots. The more something looks like a thing we can relate to, the easier it is to feel for it,” said Dr Harrison.

Science fiction also plays a role in how we relate to real-life robots like Opportunity and can influence our views about science, technology and space in the real world. “I know I definitely got interested in robots as a kid because of Johnny 5 in Short Circuit," Dr Harrison added.

There’s no shortage of human-like robots or cute robots with personalities in science-fiction stories that speak to our favourite characters – and even become our favourite characters, like C3PO, R2-D2, Wall-E, Marvin the Paranoid Android and many more.

Sure these robots don’t look exactly like rovers, but these robot characters have set a precedent for us that they can fix things, travel with us and help us – they can become our friends.

To the Red Planet and beyond

Although this may be the end for Opportunity, it’s just the beginning for Mars exploration. The Curiosity rover is already on the red planet and the InSight lander has bold plans to probe the Martian surface and find out more about how the planet is formed.

Many of those who worked on the Opportunity mission are now planning for the upcoming Mars 2020 rover, which will run a range of tests when it lands to answer some of NASA’s burning questions about the potential for life on Mars.

As these rovers explore more of the surface of Mars, we can follow along with the journeys, discoveries and selfies via social media. Although Opportunity may be gone, our links to Mars haven’t been severed – there’s still a presence there that keeps the dreams of visiting other planets alive and well.

That’s why Opportunity, rovers and spacecraft are special to us – these robotic missions remind us of how human we are.

Thanks to Voyager 1 and 2 we’ve taken a tour of our solar system, thanks to Opportunity we’ve had a presence on Mars for 14 years and become familiar with the red planet’s surface. These missions keep us connected to the cosmos and give everyone a chance to see what space is like far beyond Earth and the places we’re able to visit ourselves.

Welcome to TechRadar's Space Week – a celebration of space exploration, throughout our solar system and beyond. Visit our Space Week hub to stay up to date with all the latest news and features.

Becca is a contributor to TechRadar, a freelance journalist and author. She’s been writing about consumer tech and popular science for more than ten years, covering all kinds of topics, including why robots have eyes and whether we’ll experience the overview effect one day. She’s particularly interested in VR/AR, wearables, digital health, space tech and chatting to experts and academics about the future. She’s contributed to TechRadar, T3, Wired, New Scientist, The Guardian, Inverse and many more. Her first book, Screen Time, came out in January 2021 with Bonnier Books. She loves science-fiction, brutalist architecture, and spending too much time floating through space in virtual reality.