It's rare that a truly new technology comes along, promising to revolutionise the world. Just as the printing press and spinning jenny empowered cottage industries with the ability to spread knowledge and manufacture goods, 3D printers promise to enable a next-generation industrial revolution of home-made and customised products.

In the industrial world, 3D printing is known as Additive Layer manufacturing, which should give you a hint as to how the process works. Thin layer after layer of material is built up, in a way that means a final fully-formed widget, hip bone, gun or part is produced.

It contrasts with traditional machine lathing, which has garnered the name Subtractive manufacturing, because material is removed to make a final part.

How to print in 3D

So how can you get started with 3D printing to become part of the revolution? The short and sweet answer is you'll need a 3D printer, suitable material for that printer, a 3D model to print and suitable software to do just that. Some of the big names in 3D printing are MakerBot, Up! Plus, Afinia and the most affordable RepRap design.

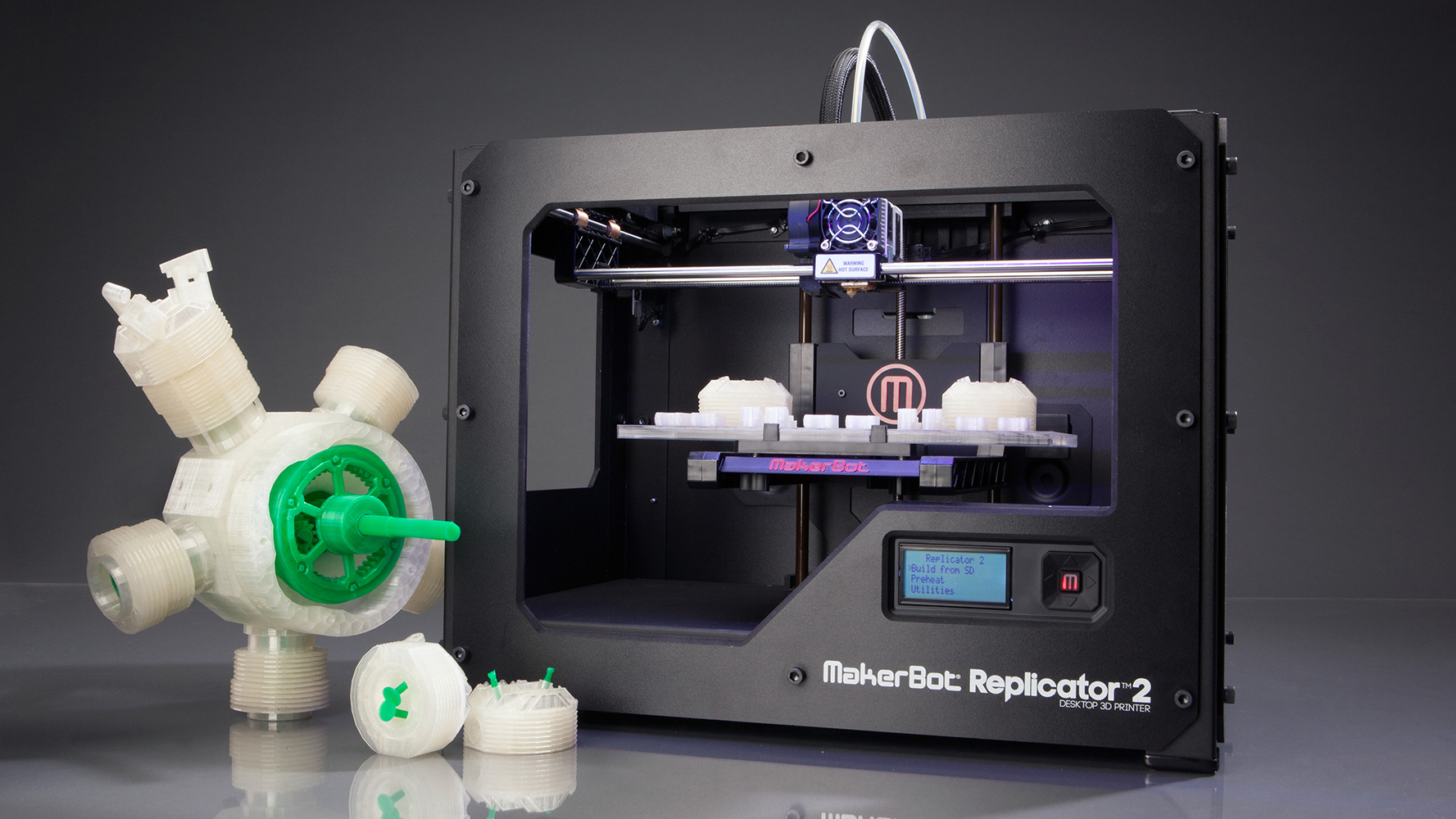

The MakerBot Replicator 2 is one of the best known 3D printers on the market, with a price tag of £1,800 / US$2,200 / AU$2,685, while 1kg (2.4lbs) of print filament costs around £52 / US$48 / AU$66. The MakerBot Replicator 2 has a print layer resolution of 0.1mm or 256dpi.

In old-school print terms this sounds almost archaic, but this is more than fine enough to print perfectly smooth, curved objects that can be as large as 285 x 153 x 155mm (11.2 x 6 x 6.1 inches).

The Up! Plus 2 printer is a good contrast because it retails for US$1,650 (around £1,055 / AU$1,735) and has a 0.15mm or 166dpi resolution and maximum print volume of 140mm cubed.

Are you a pro? Subscribe to our newsletter

Sign up to the TechRadar Pro newsletter to get all the top news, opinion, features and guidance your business needs to succeed!

Cheap 3D printers

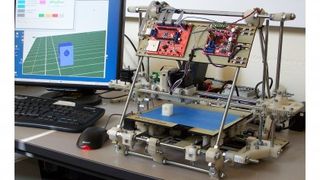

In the popularity stakes, RepRap tends to win, largely because it's the cheapest brand on the market, with self-build kits starting at around £400 / US$600 (around AU$660).

It's rather dubiously known as the 3D printer that can print itself, which is really a half-truth, since only a number of connecting parts can be created this way. The rest are metal rods and electrical components, but it's a clever sell and most designs can be built entirely at home with basic DIY tools and materials.

What really makes the RepRap interesting is it's very much an open source design. This has enabled a number of alternative designs to spring into existence from the RepRap Mendel original.

For example the RepRap Wallace is a smaller lower-cost design, while the RepRap Prusa Mendel is a larger but easier and cheaper-to-build version.

A criticism of all these RepRap variants is the wedge-frame base design, so a popular alternative to this is the RepRap Prusa i3 that uses a more rigid box frame. While the MendelMax 2.0, which is going through its beta design phase, is gaining attention as the latest iteration of that popular RepRap design.

Common to all these printer types are print materials. To produce prints these lower-cost 3D printer units generally use acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS), polylactic acid (PLA) or another member of the thermoplastic polymer family, usually supplied by the kilogram in a spools of 1.5mm thick wire, usually in a choice of different colours. As we've already said though, it's not cheap stuff.

Starting to print in 3D

Printing itself depends very much on the 3D printer you've chosen. Pre-built models such as the UP! Plus and MakerBot Replicator 2 are on the whole standalone and ready-to-go out of the box. The RepRap variants tend to be based on the Arduino USB control system, so need to be configured and run from a PC.

Typically getting a RepRap-based device up and running requires a good number of steps. These starting with installing the Arduino USB driver and development environment for the USB interface. Interfacing, communicating and supplying suitable 3D models to the RepRap requires a suite of tools. Many are built on the Python programming language, so you'll need the right build from Python.org, which is often version 2.7.